Eighteenth and Nineteenth

Century Sheffield

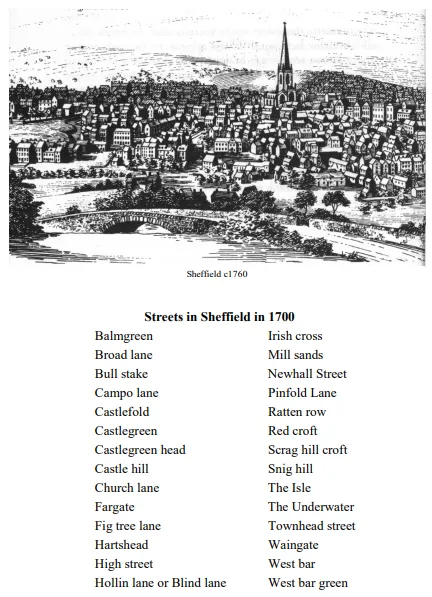

‘In 1750, Sheffield was a rookery of squalid houses at the foot of a wild moorland.’

‘Sheffield: noisy, smoky, loathsome but surrounded on all sides by some of the most enchanting countryside to be found on this planet.’

The most striking feature of 18th century Sheffield, is the physical development of the town from the century’s beginning, with a pre-industrial economy, to its end, when the Industrial Revolution had brought unprecedented social and economic changes.

At the start of the century, Sheffield’s feudal past is easily recognised with the layout of its streets and houses that still traced the ancient footpaths. Sheffield Castle had been demolished in 1648 following the Civil War, perhaps within living memory for a few locals.

Houses, almost half (45%) with a smithy attached, and shops were dotted about with no form of symmetry to the layout of the town as there had been little regulation of buildings. The town was small, consisting of just twenty-nine streets in 1700, although another source states thirty-five streets, lanes and passages. This may have been deduced from the first map of Sheffield produced by Ralph Gosling in 1736.

Many of these thoroughfares had open sewers running down their middle, which also served as household refuse dumps. These were infrequently washed clear, about four times a year, and flushed into the River Dun (Don) using water from Barker’s Pool at Balm Green, a reservoir fed by natural springs dating back to 1434.

During the 17th century, it was used on occasions for the ducking of turbulent women on the cuck stoole. By the late 18th century, Barker’s Pool was a walled water enclosure built by Robert Rollinson measuring 36 yards by 20 yards, although it was not a true right-angled quadrilateral as the eastern end was slightly wider than the other (see map below).

Towards the end of the century, it became unfit to drink and was used purely to flush the gutters and put out fires. James Wills (1774-1827), a Sheffield tailor and poet, described it in a verse in its final days:

’The Barker’s Pool, noted for nuisance indeed,

Green over with venom, where insects did breed,

And forming a square, with large gates to the wall,

Where the Rev. Charles Wesley to sinners did call.’

It was removed in February 1793 and houses were built on the site, the first by Mrs Hannah Potter, which was a public house called Well Run Dimple, alluding to a horse that had distinguished itself at the Crookes Moor races and may have landed Hannah Potter a decent winning bet.

Samuel Roberts (1763-1848) gives us a contemporary account of the cleansing of the gutters:

-

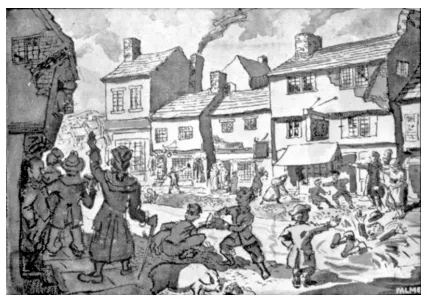

“All the channels were then in the middle of the streets, which were generally in a very disorderly state, manure heaps often lying in them for a week together. About once every quarter the water was let out of Barker Pool, to run into all those streets into which it could be turned, for the purpose of cleansing them. The bellman gave notice of the exact time, and the favoured streets were all bustle, with a row of men, women, and children on each side of the channel, anxiously and joyfully awaiting, with mops, brooms, and pails, the arrival of the cleansing flood, whose first appearance was announced by a long, continuous shout. All below was anxious expectation; all above, a most amusing scene of bustling animation. Some people were throwing the water up against their houses and windows; some raking the garbage into the kennel; some washing their pigs; some sweeping the pavement; youngsters throwing water on their companions, or pushing them into the wide-spread torrent. Meanwhile a constant, Babel-like uproar, mixed with the barking of dogs and the grunting of pigs, was heard both above and below, till the waters, after about half an hour, had become exhausted.”

Flushing the streets with water from Barker’s Pool.

Early governance of Sheffield was undertaken by the Court of the Lords of the Manor. In 1297, the people of the town were given some control of affairs by a charter granted by Thomas Lord Furnival and the town Burgesses came into existence. By a charter of Queen Mary in 1554, The Twelve Capital Burgesses and Commonality, also known as the Church Burgesses, became a Corporation with a Common Seal.

During the 17th century, the twelve Burgesses became thirteen and formed into a body of Trustees, later becoming the Town Trustees. Whilst purporting to be a representative body of the people of Sheffield the Town Trustees were in essence a board of select and wealthy elite, predominantly land-owners, aristocrats and country gentlemen, driven by self-interest and who were not elected by the people but appointed from amongst their own social circle, and they often generated discontent.

Little changed into the 19th century, as in 1825, an anonymous pamphlet was published and sold in all of the town’s book shops for 6d. The author of this pamphlet, calling himself ‘A Commissioner’, with the subtitle Secresy [sic] in Public Trusts is always either the Parent or Offspring of Mismanagement, if not Peculation, attacked the methods of the proceedings of local government:

-

The government of this town appears to me to be in the hands of some six to eight respectable families, united by marriages, inter-marriages, and intimate connections, into what may be called a Family Compact, or, perhaps, a Holy Alliance, always able, by their united efforts, to overturn or overbear all measures or individuals opposed to the interests of any member of this self-incorporated body. They are likewise able to carry any measure which they are determined to promote. The ramifications of their influence penetrates every avenue of the town, and can secure the co-operation, when required, of all whom they employ, from the opulent banker, to the most despised and oppressed of the human race, the wretched substitute for a sweeping-machine.

That the price of this leaflet being 6d suggests that it wasn’t primarily aimed at the working class but to bring, what the author thought, were corrupt practices, including the alleged embezzlement of the Trust’s money, to the notice of the middle and upper classes, from which the Trustees were drawn, including, by now, the industrial capitalists whose new-found wealth gained them acceptance into the realms of government. Throughout the ages, power, corruption and greed have been ready companions.

In 1843, Sheffield was incorporated as a municipal borough with nine wards and governed by a Town Council consisting of a Mayor (the first Mayor of Sheffield was William Jeffcock), 14 aldermen and 42 councillors.

At the beginning of the 18th century, the Town Trustees found it necessary to employ someone, known as a Scavenger, to sweep Lady’s Bridge, Truelove’s Gutter (now Castle Street) and the pavements at the Church gates. The annual salary was 13s-4d but there were other expenses for buying a muck drag and cow-rake and for leading away the rubbish.

In 1769, some colliers were employed to clean Truelove’s Gutter and were paid £1-11s-6d. In 1775, James Turton was paid £2-10s to clean the streets of the town but the service was probably limited to the busiest thoroughfares. In April 1795, the Trustees agreed a contract with Robert Taylor to keep the streets of Sheffield clean for one year for which they paid him £80; he was also allowed to keep the manure, which would be plentiful at this time and was a saleable commodity.

By this time, more thought had been given to the job and in 1801, John Hall was paid 8s for devising a cask for the scavengers to water the streets. By 1805, Robert Taylor was also employed to sweep the market on Sunday mornings for 19s-4d. In 1810, Taylor was still cleaning the Sheffield streets but he was now being paid £105. The contract stipulated that he must find his own horse and cart and all necessary tools and implements, but he could still keep the manure.

Samuel Roberts

There was no street lighting until 1734, when a process of gradually providing oil lamps in appropriate places was introduced. But these were initially few and far between and only lit in the winter months. The Town Trustees paid a Mr Parkin £3-15s-11d for their lighting. In 1747, a job was created to light, clean and take care ...