- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

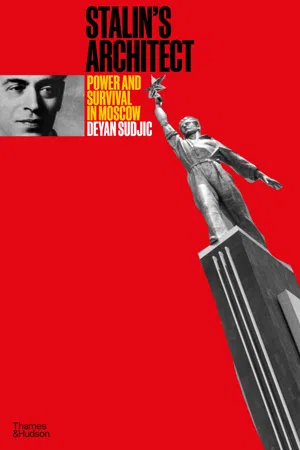

This is a history of architecture, politics and power. Boris Iofan (18911976) made his mark as Stalins architect, both in the grand projects he achieved, such as the House on the Embankment, a megastructure of 505 homes for the Soviet elite, and through his unbuilt designs, in particular the Palace of the Soviets, a baroque Stalinist dream whose iconic image was reproduced throughout the Soviet Union. Iofans life and designs offer a unique perspective into the politics of twentieth-century architecture and the history of the Soviet Union.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

ArtSubtopic

Artist Biographies1

Odessa and St Petersburg

Like many of his fellow 20th-century architects, including Le Corbusier, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and Frank Lloyd Wright, Boris Mikhailovich Iofan began his career by redesigning his own name. He was born Borukh Solomonovich Iofan on 28 April 1891 in the Black Sea port city of Odessa, to Solomon and Golda Iofan.

Odessa’s art school, where both Iofan and his brother Dmitry studied, taught many of the Soviet Union’s most creative painters and sculptors.

Russian Jews at this time were obliged to adopt national naming conventions, assuming a surname (not generally part of Jewish tradition) as well as a patronymic. A name change in tsarist Russia was no small matter, subject to close imperial regulation: from 1850 until the revolution, even baptised Jews were prohibited from changing their surnames without permission. In 1882 Alexander III had introduced a set of new laws that made life even more difficult for Jews, removing their right to vote in local elections or mortgage property and restricting their access to higher education with the imposition of quotas.

Iofan is a version of a more widely used Hebrew name, Jaffe, which has its roots in Prague. It was never common in Odessa, and in Boris Iofan’s time there were no more than two or three families in the city who shared it. Before the revolution, the only legal way for the Iofans to take new names would have been to convert to Christianity. If they did this, it must have been after 1901, when Boris’s elder brother Dmitry (b. 1885) graduated from Odessa’s school of art and was still using his birth name, Shmul Iofan.

But based on Boris’s later experience of being restricted in his studies by the quota laws, it seems more likely that the family never converted and simply rejected all religious associations. Boris, Dmitry and their sisters Raisa (b. 1885) and Anna (b. 1892) all adopted Mikhailovich or Mikhailovna as patronymic middle names in the Russian manner, rather than Solomonovich or Solomonovna. Changing his name was Iofan’s response to Russia’s vicious anti-Semitism – which existed both before and after the revolution – as well as a reflection of his embrace of militant secularism, which culminated with him joining Italy’s Communist Party in 1921.

Boris’s moderately prosperous parents did not have access to the Odessa of the very rich, with its seaside villas and private clubs, where English newspapers and French magazines were available in the same week they were published. Nor did they experience the squalor of Moldavanka, a sprawling shanty town on the city’s north-eastern edge where day labourers and the destitute struggled to survive in a vodka-dulled haze of flophouses, licensed brothels and petty crime. They were somewhere in the respectable middle; Solomon Iofan probably made his living running a hotel. Later, when Soviet social engineering made even the most modest sign of privilege inadvisable, Boris apparently downgraded his father’s occupation to the more proletarian-sounding one of hotel doorman, which is how he is described in Soviet-era reference books. His uncle Iosif was an engineer with an agricultural equipment business in the town of Aleksandrovsk on the Dnieper River; by 1913 he had set up a subsidiary in Odessa, using Boris’s family home as its official address.

Boris Iofan grew up in this apartment building near the centre of Odessa. His family had academics and businessmen as neighbours. The pair of classical atlantes guarding the entrance suggest an early inspiration for his use of the human figure as an architectural element.

The Iofans lived in a rented apartment on Elizavetskaya Street, one of a grid of tree-lined avenues marking out Odessa’s city centre. Their home occupied part of a floor of number 1, a substantial four-storey building dating from the 1840s, designed in the form of a palazzo with a rusticated base and pilasters two storeys high supporting an entablature and a pediment. At the time they moved in, the building had been newly remodelled by César Zelinsky, a leading local architect. Zelinsky had embellished the entrance arch that gave access to the block’s inner courtyard with a pair of atlantes, classical figures visibly struggling from the effort of carrying the whole world on their bare shoulders.

There is a photograph of Iofan as a baby, balanced on his mother’s knee; she is a darkly elegant, fine-featured woman. Iofan’s brother stands with them in an elaborately buttoned tunic and Eton collar. Their father, in a frock coat and neatly trimmed beard, sits next to his wife with their elder daughter in his arms. The family group presents a picture of middle-class respectability.

Diagonally across the street from the Iofans’ home was what had previously been the Lycée Richelieu, Odessa’s first elite secondary school, built in classical style on Deribasovskaya Street. By the Iofans’ time, however, the original Lycée building was occupied by Novorossiisk University (where the young Leon Trotsky briefly studied) and the secondary school had moved to Elizavetskaya Street. Further along the street was a fashionable hydropathic establishment built in elaborate Moorish style, where the city’s affluent residents indulged themselves in mud baths and spa treatments. The Iofans’ neighbours included lawyers, academics and a number of scientists.

All the Iofan siblings had the benefit of an education. Boris and Dmitry became successful architects, while Anna was a teacher and moved to Moscow when the revolution removed restrictions on residency there. Raisa worked in Odessa as a midwife before she too relocated to Moscow; as adults, for a time, she, Anna and Boris lived in adjoining homes in an apartment building on Rusakovskaya Street. Golda, their mother, died in Moscow in 1930 and is buried in the city’s Novodevichy Cemetery. The remains of Boris and his wife Olga are also marked there by a modest memorial of his own design.

The Iofans lived during a period of extreme disruption that included civil unrest, pogroms, two world wars, a revolution, a civil war and a series of purges, as well as the Holocaust. Throughout decades of turbulence and appalling violence – affecting all Russians, but particularly targeted towards the Jewish population – somehow the whole family not only survived, but maintained their closeness.

During Boris’s childhood, Odessa was a boom town. Its harbour was full of ships servicing the grain trade that underpinned the city’s economy. At the time of his birth it had a population of 400,000, having doubled in size over the previous decade; by the time he left for St Petersburg in 1911, this had grown to 650,000. From 1911 onwards, there was an electric tram network. With its department stores, fashionable restaurants, shopping arcades and a museum of art and archaeology boasting an impressive collection of Hellenic antiquities, it certainly looked the model of a modern city. As with the rest of Russia, however, it was becoming clear that Odessa’s prosperity rested on an unstable foundation of social inequality and was undermined by an arbitrary, incompetent central government.

For much of the 19th century Odessa, fast-growing and cosmopolitan from its first foundation, offered more opportunities than were available elsewhere in the so-called Pale of Settlement – the zone Catherine the Great had defined as being open to her Jewish subjects, in legislation that also served to exclude them from every other part of Russia. The restrictions on the occupations open to Jews elsewhere in the empire did not apply in Odessa; the city allowed residents who had come from anywhere the chance to make money legally in any way that they could. If they made enough of it, they lived and spent it wherever they wished.

These were attractions that drew migrants from all over Europe. In 1850, one Odessa citizen in five was Jewish. When Iofan was born the city had 140,000 Jewish residents – 35 per cent of the population – making Jews second in number only to the city’s ethnic Russians. St Petersburg, where Jews were required to secure a residency permit, had fewer than 20,000 Jews in a population of more than a million people.

Jewish life in Odessa was very different from the conservative traditions of rural Eastern European Jewry at the time. The city developed a secular culture that provoked sharp conflict between modernizers and the Orthodox devout. Many Jews, Boris Iofan among them, saw assimilation into contemporary Russian society as the only way forward. But during his teenage years, two-thirds of the city’s Jewish students still spoke Yiddish rather than Russian at home – and it was in Odessa that the Zionist movement took shape, spurred on in part by recurring pogroms that reached a horrifying climax in three days of appalling bloodshed witnessed by fourteen-year-old Boris in October 1905. If helping to modernize Russia was not going to be open to them, the Zionists resolved to build a progressive state of their own.

These disparate and conflicting strands contributed to the development of a distinctive Jewish Odessa, one that had its own approach to culture, religion and politics and would influence other Jewish communities. The city set a model for modern forms of religious observance and was also a vibrant centre for secular Jewish life, particularly in the areas of music and Yiddish theatre. The celebrated writer Isaac Babel, a contemporary of Iofan’s, used his memories of growing up in the city for Odessa Tales, a collection of short stories exploring the criminal underclass that dominated the Moldavanka area.

While Odessa’s Jewish roots were an important part of its character, they represented only one aspect of the rich cultural mix in which Iofan grew up. At the end of the 19th century, the city’s ethnic diversity gave it a character more akin to contemporary Constantinople, Salonika or Trieste – each with Greek, Slav, Jewish and Turkish quarters that had their own schools, religion and cuisine – than to the western Mediterranean port cities of Marseilles or Genoa with which it was often compared. Like Shanghai in the 1920s, an extra-territorial port run by foreigners on Chinese soil, the business life and administration of Odessa was contracted to others by Imperial Russia. The city had a French-language newspaper before it had a Russian one, and in the early days its street signs were produced in Italian as well as Russian for the benefit of citizens unfamiliar with Cyrillic script. The foundation stone for the opera house was laid before that of the Russian Orthodox cathedral.

During the 19th century Odessa had been transformed with remarkable speed from a Tartar settlement of a few hundred people, built around a Turkish fortress, to the fourth-largest city in the Russian empire after St Petersburg, Moscow and Warsaw. This process was a systematically planned piece of Imperialist expansionism. From 1795 onwards, the city leaders set out to attract ambitious and economically useful colonists of whatever nationality: ethnic German farmers, Italian architects, Greek traders. Its streets were populated by members of all of these groups along with Bulgarians, Turks and Albanians, some habitually in national costume, others fashionably dressed in modern metropolitan style.

Russia gave classically inspired names to the new cities it established in its recently conquered territories (collectively known as Novorossiya – New Russia) to suggest that they had roots in ancient Greece. Odessa is named in tribute to Odysseus; Sevastopol is a derivation of Greek words for the ancient, venerable, or holy city; Tiraspol in Moldavia takes its name from Tyras, the Greek name for the Dniester River. All this seems to have been a carefully considered branding strategy, aimed at encouraging settlers from western Europe and peeling back the traces of Mongol, Tartar and Turkic history to give the impression of a modern city with ancient European roots.

Armand-Emmanuel de Vignerot du Plessis, Duc de Richelieu, was the first of a series of governors whose shrewd policies ensured that Odessa had an openness unusual in the Russian empire. Richelieu, a descendant of Louis XIV’s famous cardinal, had been a French royalist and a soldier in the service of Marie Antoinette. Having escaped from the revolution in Paris that saw his monarch guillotined, he offered his services to the Russian empire. He then distinguished himself in the Russian army and was appointed governor of Odessa in 1803.

Odessa owed its prosperity and its place as the fourth-largest city in the Russian empire to its harbour and its privileges as a free port. Grain from its Ukrainian hinterland was exported around the world. During the Potemkin mutiny of 1905, the battleship moored here, provoking serious bloodshed.

Richelieu set out to strengthen the city’s Greek origin myth by investing in neoclassical architecture. He commissioned the Swiss-French architect Jean-François Thomas de Thomon, responsible for some of St Petersburg’s finest buildings, to design Odessa’s opera house, which opened in 1810. Odessa’s City Hall, originally built to house the city’s Bourse, followed in the 1820s. It was designed by Francesco Boffo and Gregorio Torcelli in a style that acknowledged de Thomon’s work, with a giant Corinthian colonnade as the dominant element of its main façade. Richelieu’s successor was Comte Louis Alexandre Andrault de Langeron, another aristocratic French exile and soldier with an equally impressive military record: he had fought against the British in the American revolutionary war and then against Napoleon in Europe. De Langeron succeeded in turning Odessa into a free port, a status it retained for the next forty years and that represented another vital step in its strategic development.

Francesco Boffo became Odessa’s official architect. He built the governor’s palace for Mikhail Vorontsov (the city’s first Russian-born governor, a Cambridge-educated anglophile); he also designed the Primorsky Boulevard, a promenade lined by palatial houses following the cliff-top shoreline. It is the most impressive piece of urban scenery in the city. Its centrepiece is a handsome, larger-than-life bronze statue of Richelieu standing on a marble plinth. He is portrayed as a young man dressed in a Roman toga, his brow garlanded with a laurel wreath.

Boffo’s most famous work, however, is one of Europe’s grandest staircases. The 200 treads of the Odessa Steps, arranged in ten flights, linked the cliff-top city with its port, allowing the refined neighbourhoods above to look down on the quarantine harbours, jetties and raw docks below. An English engineer of dubious reputation was engaged to build the monumental installation, using sandstone shipped from Trieste for the steps. The stone quickly eroded in the salt air, and the steps have since been relaid using harder-wearing local granite.

The flaking stone steps are famously seen in close-up during Sergei Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin massacre scenes, filmed in Odessa in 1925. The success of the film led to the staircase being renamed the ‘Potemkin Steps’ during the Soviet era, even though the events Eisenstein depicted – a runaway pram and advancing ranks of soldiers carrying rifles with bayonets fixed, shooting down ordinary citizens who crumple and fall, all seen cinematically through a pair of smashed spectacles – did not take place as he portrayed them.

The steps are set out at an angle that makes them seem to disappear when viewed from the summit, leaving only the ten flat landing levels visible. Looking up from the level of the harbour, it is the horizontal landings that become invisible while the steps appear as a solid, visually dominant vertical wall. Boffo made them considerably wider at the bottom than the top, creating an optical illusion that accentuated the effect of perspective and made the Richelieu statue appear larger and more impressive when seen from below.

Odessa sits on a headland connected to its port by the famous steps. A statue of the Duc de Richelieu, the city’s first governor, stands at the top. Iofan’s plan for the Soviet pavilion in Paris put Stalin in a similar position, at the head of the central stairway.

It is easy to see how the image of Richelieu’s bronze head strikingly juxtaposed against the architectural context of Odessa would have become an essential point of reference for Iofan, a young art student with highly developed powers of observation who spent his time haunting the city’s public spaces and exploring its architectural features. The atlantes flanking the entrance to his Elizavetskaya Street home were another key image. Clear traces of his memories of Odessa – most strikingly, the steps and the figures – can be found in his own later work. His memory of the Odessa Steps may have had something to do with the organization of the interior of his Soviet pavilion at the 1937 Paris Exposition: it had a sequence of broad stairs interrupted by landings as its centrepiece, with a statue of Lenin as its climax. Iofan positioned a GAZ limousine, the unreliable pride of the fledgling Soviet car industry, on the first landing.

Odessa’s embrace of its coastal setting served as a precedent for Iofan’s approach to the rebuilding of Stalingrad and Novorossiisk after their wartime destruction. In each case, his masterplan made use of the city’s relationship with water as a starting point. Little more than a fragment of Iofan’s plan for Novorossiisk was realized, however; and there is nothing at all of his plan in Stalingrad, or Volgograd, as it is now.

Richelieu had envisioned Odessa as a southern version of St Petersburg, an elegant, cultured city without the winter ice. But by the time the Iofan brothers were growing up there, the city’s grandeur and coherence had become blurred by the reality of urban life in a boom town. Half a century of continuous growth had made it a brasher and more ostentatious place than Richelieu or de Langeron had anticipated. Every new building competed with its predecessors in an attempt to present the most ornate and elaborately over-decorated façade. The neoclassical purity of the Bourse was compromised by Francesco Morandi’s alterations of 1871, when he turned it into the City Hall. Thomas de Thomon’s chaste Doric opera house burned to the ground and was replaced in 1886 with a blowsy but briefly fashionable new building designed in Vienna by Ferdinand Fellner and Hermann Helmer, whose partnership became an architectural production line that eventually churned out more than forty theatres, opera houses and concert halls throughout th...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- About the Author

- Other Titles of Interest

- Contents

- Introduction

- 1. Odessa and St Petersburg

- 2. Rome

- 3. Moscow

- 4. Palace of the Soviets

- 5. Paris and New York

- 6. War

- 7. Post-War

- Epilogue

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Acknowledgments

- Picture Credits

- Index

- Copyright

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Stalin's Architect by Deyan Sudjic in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Artist Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.