eBook - ePub

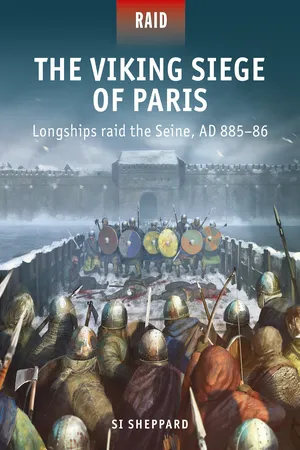

The Viking Siege of Paris

Longships raid the Seine, AD 885–86

- 80 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The Vikings' siege of Paris in 885–86 was a turning point in the history of both Paris and France. In 885, a year after Charles the Fat was crowned King of the Franks, Danish Vikings sailed up the Seine demanding tribute. The Franks' refusal prompted the Vikings to lay siege to Paris, which was initially defended by only 200 men under Odo, Count of Paris, and seemingly in a poor state to defend against the Viking warriors in their fleet of hundreds of longships.

Paris was centred around the medieval Île de la Cité, the natural island now in the heart of the city, fortified with bridges and towers. The Vikings attempted to break the Parisian defenders, but the city itself still held out, and after a year Charles' army arrived to lift the siege. But Charles then allowed the Vikings to sail upstream against the revolting Burgundians. Outraged at this betrayal, the Parisians refused to let the Vikings return home via the Seine, forcing them to portage their boats overland to the Marne in order to reach the North Sea. When Charles died in 888, the people of the of the Île de France elected Odo as their king. The resistance of Paris therefore marked the end of the Carolingian line and the birth of a new kingdom.

This fully illustrated volume, accompanied with maps and strategic diagrams tells the full story of the Vikings' expedition to conquer medieval Paris, highlighting a key moment in the history of France and its foundation as a nation.

Paris was centred around the medieval Île de la Cité, the natural island now in the heart of the city, fortified with bridges and towers. The Vikings attempted to break the Parisian defenders, but the city itself still held out, and after a year Charles' army arrived to lift the siege. But Charles then allowed the Vikings to sail upstream against the revolting Burgundians. Outraged at this betrayal, the Parisians refused to let the Vikings return home via the Seine, forcing them to portage their boats overland to the Marne in order to reach the North Sea. When Charles died in 888, the people of the of the Île de France elected Odo as their king. The resistance of Paris therefore marked the end of the Carolingian line and the birth of a new kingdom.

This fully illustrated volume, accompanied with maps and strategic diagrams tells the full story of the Vikings' expedition to conquer medieval Paris, highlighting a key moment in the history of France and its foundation as a nation.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Viking Siege of Paris by Si Sheppard,Edouard A. Groult in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & French History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

THE SIEGE OF PARIS

The medieval city on the Seine

Paris in 885 was not the capital of the Carolingian realm, and far from its largest urban conurbation, but the city was wealthy and storied, boasting one of the longest records of permanent settlement in Europe north of the Alps.

It was during the Iron Age, sometime around 250 BC, when the Celtic tribe of the Parisii made their home around the cluster of islands 4 miles downstream from where the Marne joins the Seine. The settlement was first described by Caesar in his Commentaries on the Gallic Wars as ‘a town of the Parissi, situated on an island in the river Seine’. His senior legate, Titus Labienus, fought a decisive battle here in 52 BC. After conquering Gaul, the Romans built the city of Lutetia atop the ruins of the old Parisii settlement. Due to its location athwart an important road nexus, Lutetia grew in importance, becoming the capital of provincial Western Gaul by the end of the 4th century; the emperor Julian was crowned in his ‘beloved Lutetia’ in 360.

A view from the Right Bank of the Seine towards the Île de la Cité, the grand prize for the Viking raiders when they initiated the siege of 885. The key to taking the city was securing the Grand Châtelet tower that protected the Grand Pont bridge where it connected to the shore on the left of this image. (Getty)

After the collapse of the Roman Empire in the West, the name of the city reverted to Civitas de Parisii, which eventually contracted to Paris. While its political significance diminished, because of its strategic location Paris remained a major hub on those trade routes that survived the economic contraction of the 5th century. The city also cultivated a reputation for piety, beginning in the 3rd century with the martyrdom of St Denis, later venerated as the patron saint of both Paris and France. This tradition was enhanced by St Geneviève, who faced down Attila the Hun in 451 and baptized the Frankish warlord Clovis in 496. It was Clovis who was responsible for constructing the church of St Martin-des-Champs on the Right Bank of the Seine and the cathedral of St Étienne on the Île de la Cité itself. The 7th-century Frankish King Dagobert I added to this panoply of ecclesiastic landmarks by founding the abbey of St Denis as a Benedictine monastery, later complemented by a church, construction of which began in 754 under Pepin the Short and was completed under Charlemagne, who was present at its consecration in 775. According to the Vita of St Eligius, the mausoleum of the martyred saint was completed ‘with a wonderful marble ciborium over it marvellously decorated with gold and gems’. St Eligius:

A battle scene from the Liber I Machabaeorum. The Carolingian realm included a large number of fortified places of various origins, a combination of royal palaces, urban centres and more rural late Roman and early medieval fortresses – dubbed fluchtburgen (‘flight fortresses’) in East Francia – to which the local populace would flee when faced with foreign invasions or raids. (Leiden University Libraries Digital Collections/CC-BY-4.0)

surrounded the throne of the altar with golden axes in a circle. He placed golden apples there, round and jewelled. He made a pulpit and a gate of silver and a roof for the throne of the altar on silver axes... So much industry did he lavish there, at the king’s request, and poured out so much that scarcely a single ornament was left in Gaul and it is the greatest wonder of all to this very day.

Such opulence motivated the sojourns of countless pilgrims, but would ultimately attract much less desirable attention. The wealth of Paris, in addition to its location athwart one of the major navigable rivers in France, made it a natural target for Viking raiders. The city was sacked in 845 by Ragnar, in 857 by Björn Ironside, and again in 861. After a quarter-century of relative peace, the supreme test would come in 885, when the Viking host arrived beneath the walls on or about 24 November.

The raiders easily occupied the settlements on both the right and left banks of the Seine, which had been conceded by the garrison as indefensible. Lacking the manpower to establish a perimeter around all of Paris, the Franks elected to evacuate the entire population and make their stand on the Île de la Cité. Even the Île de la St-Louis, which was roughly half the size of its neighbouring island and was used mainly as pastureland, was left undefended. The records give no indication as to whether the Franks opted to burn down the suburbs before the Vikings arrived as a component of a scorched earth policy.

The defensive walls constructed by the Romans on the Île de la Cité largely followed the outline of the island. They enclosed an area of 8 hectares measuring 490m long and 180m wide. Within this space were the royal palace, in which Odo lived, located in the western section of the Île de la Cité, while to the east were the church of St Étienne, to which were joined the Basilica of Notre-Dame and the Baptistery of St Jean-le-Rond; these three ecclesiastical buildings were under the direct rule of Bishop Gauzlin.

The builders attempted to place the walls as close as possible to the water’s edge, but the marshy and muddy banks of the Île de la Cité permitted only approximately half of the island to be enclosed. Due to the uneven terrain, the actual height of the walls varied from 12–25ft (3.66–7.62m), placing the top of the wall at roughly uniform level. From 8ft (2.44m) thick at the base, the walls tapered to 6ft (1.83m) at the parapet.

These fortifications constituted the secondary line of defence for the garrison. The primary challenge for the Norsemen to overcome was the River Seine itself; its swift current acted as a natural moat surrounding the Île de la Cité, which was connected to the left and right banks of the river by two low-slung fortified bridges that barred the raiders from further progress upstream. They could be ported around, but the Vikings would be reluctant to leave an unsubdued, fortified garrison in their rear commanding their primary egress from the heartland of France.

The shorter bridge, the Petit Pont, which linked the island to the south (west) bank, was constructed of wood. Its bridgehead was fortified by a wooden tower dubbed the Petit Châtelet. Aligned with Rue St Denis, the longer, northern span – the Grand Pont – was made out of stone, with crenellations along its length. Its bridgehead was defended by the stone Grand Châtelet tower, which was only partially completed. Nevertheless, its foundations were solid and stood firmly grounded, surrounded by defensive ditches at its base.

The two key figures in the defence of Paris reflected the duality of Church and State in the Carolingian world. The former was represented by Gauzlin, who had succeeded Engelwin as Bishop of Paris the previous year. Over the course of his career, he had straddled the inner circles of both royal and ecclesiastical power, and had accrued much bitter personal experience of Viking prowess in battle. The son of Rorgon I, Count of Maine, Gauzlin – who entered the priesthood as a monk in 848 – had risen to become abbot of the great monastery at St Maur-sur-Loire in 858 when he and his half-brother, Louis, were abducted and held for an exorbitant ransom by the Norsemen. In 860, he joined the chancery at the West Francia court of Charles the Bald as a notary, and succeeded Louis as archchancellor in 867. He accompanied Charles in some capacity on campaign against Louis the Younger of East Francia in 876. Charles was completely defeated at the battle of Andernach on 8 October, and Gauzlin was taken prisoner. He survived, and returned to serve as archchancellor in the court of the West Francia kings Louis the Stammerer and Louis III, a position he retained despite his defeat on the Meuse in 880. He had played a critical role in the ascendancy of Charles the Fat in West Francia, subsequently securing the see of Paris for himself.

Secular authority was vested in Odo, who had probably become Count of Paris in succession to Conrad by the end of 882 or the beginning of 883. His family had not enjoyed an altogether harmonious relationship with the Carolingian court. His father, Robert the Strong, had rebelled against Charles the Bald, and although later ostensibly reconciled, in 868, according to the Annals of St Bertin, ‘Those of Robert’s honores which Charles had granted to his son after his father’s death were now taken away and distributed among other men.’ The primary beneficiary was Hugh, abbot of Saint-Germain d’Auxerre, a son of Conrad I, Count of Auxerre. After his father died, his mother, Adelaide of Tours, married Robert the Strong, making he and Odo half-brothers. When Robert died, it was Hugh who inherited his adoptive father’s abbacies, counties and title as Margrave of Neustria.

Odo had subsequently benefitted from the influence at court of the well-connected Count Aledramnus of Beauvais, whose daughter, Theodrada, he married. Ironically, there was also friction between the families of Gauzlin and Odo. In 861, Charles the Bald had created the March of Neustria and placed it under the authority of Robert the Strong. Gauzlin’s brother, Rorgon II, who had succeeded their father as Count of Maine, revolted against Robert, allying with Salomon of Brittany for the purpose. Nevertheless, the shifting kaleidoscope of Carolingian court politics notwithstanding, Odo and Gauzlin were able to put this bad blood behind them and present a united front to the Viking threat. By the time the Norsemen arrived beneath the walls of Paris, Gauzlin had another personal grudge to nurse against them. When Rorgon II died in 865, he was succeeded as Count of Maine by another brother, Gauzfrid. Upon his demise in 878, the title passed to his cousin, Ragenold, who was killed in the encounter with the Vikings outside of Rouen seven years later.

The Vikings arrive

In reconstructing the siege, we are fortunate to have the account of a contemporary, Abbo Cernus, a native of Neustria who in 885 was a young monk and a deacon (conlevita) in the abbey of St Germain-des-Prés on the Left Bank of Paris. In Abbo’s own words, ‘let no man speak of this fight, as if he knew more. Indeed, no man may speak of these events more truly than I, for I saw everything that happened with my very own eyes.’ His narrative of the defence of Paris is chronicled in an epic poem, the Bella Parisiacae Urbis (Battles of the City of Paris), which reflects the literary and stylistic affectations of the genre, but nonetheless incorporates a wealth of first-person detail otherwise lacking in the histories of the era.

According to Abbo, the Viking fleet was comprised of ‘seven hundred high-prowed ships and very many smaller ones, along with an enormous multitude of smaller vessels’. This host was so vast that it covered the Seine ‘for a distance that extended more than t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Origins

- Initial Strategy

- The Plan

- The Siege of Paris

- Aftermath

- Conclusion

- Further Reading

- eCopyright