- 80 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

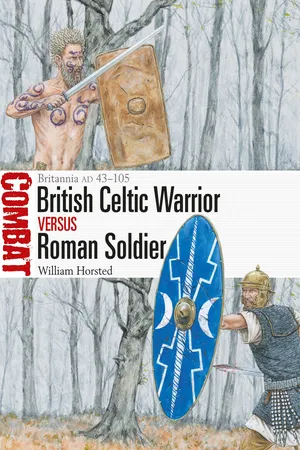

An illustrated study of the British tribal warriors and Roman auxiliaries who fought in three epic battles for control of Britain in the 1st century AD.

Following the Roman invasion of Britain in AD 43, the tribes of the west and north resisted the establishment of a 'Roman peace', led in particular by the chieftain Caratacus. Even in the south-east, resentment of Roman occupation remained, exploding into the revolt of Boudicca's Iceni in AD 60. Roman auxiliaries from two particular peoples are known to have taken part in the invasion of Britain: the Tungrians, from what is now Belgium, and the Batavians, from the delta of the River Rhine in the modern Netherlands. From the late 80s AD, units of both the Batavians and the Tungrians were garrisoned at a fort at Vindolanda in northern Britain. The so called 'Vindolanda tablets' provide an unparalleled body of material with which to reconstruct the lives of these auxiliary soldiers in Britain.

Featuring full-colour maps and specially commissioned battlescene and figure artwork plates, this book examines how both the British warriors and the Roman auxiliaries experienced the decades of conflict that followed the invasion. Their recruitment, training, leadership, motivation, culture and beliefs are compared alongside an assessment of three particular battles: the final defeat of Caratacus in the hills of Wales in AD 50; the Roman assault on the island of Mona (Anglesey) in AD 60; and the battle of Mons Graupius in Scotland in AD 83.

Following the Roman invasion of Britain in AD 43, the tribes of the west and north resisted the establishment of a 'Roman peace', led in particular by the chieftain Caratacus. Even in the south-east, resentment of Roman occupation remained, exploding into the revolt of Boudicca's Iceni in AD 60. Roman auxiliaries from two particular peoples are known to have taken part in the invasion of Britain: the Tungrians, from what is now Belgium, and the Batavians, from the delta of the River Rhine in the modern Netherlands. From the late 80s AD, units of both the Batavians and the Tungrians were garrisoned at a fort at Vindolanda in northern Britain. The so called 'Vindolanda tablets' provide an unparalleled body of material with which to reconstruct the lives of these auxiliary soldiers in Britain.

Featuring full-colour maps and specially commissioned battlescene and figure artwork plates, this book examines how both the British warriors and the Roman auxiliaries experienced the decades of conflict that followed the invasion. Their recruitment, training, leadership, motivation, culture and beliefs are compared alongside an assessment of three particular battles: the final defeat of Caratacus in the hills of Wales in AD 50; the Roman assault on the island of Mona (Anglesey) in AD 60; and the battle of Mons Graupius in Scotland in AD 83.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access British Celtic Warrior vs Roman Soldier by William Horsted,Adam Hook in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & British History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

The Opposing Sides

RECRUITMENT AND TRAINING

Roman

The Roman Army of the 1st century AD reflected the social divisions inherent in the empire as a whole: between slave and free-born, Roman citizen and provincial subject, aristocrat and commoner. Slaves were not permitted to join the Army. Nor were freedmen (those born into slavery but granted freedom later in life), though when the empire was desperately short of soldiers, special units were raised from freedmen and slaves manumitted for the purpose. The legions, the specialist heavy infantry that formed the core of the Roman Army, were only open to freeborn Roman citizens, most of whom lived in the Italian peninsula and southern Gaul. The auxiliary cavalry and infantry (from the Latin word auxilia – literally ‘the help’) were recruited from the vast population of the many provinces of the empire. These peregrini lived under imperial rule but did not enjoy the same status as citizens. Senior officers of both the legions and the auxiliary units were drawn from the ruling equestrian and senatorial classes, who were eligible to hold political office. Military service for them was essential in order to progress through the ranks of the imperial hierarchy.

Service in the legions was voluntary. Legionaries usually joined as young men of 17 or older, and remained in the Army for 25 years, should they live that long. They were reasonably well paid, at least in relation to free agricultural labourers, and could expect regular meals, a high standard of accommodation when not on campaign, and the prospect of rewards and their share of any spoils or bounty gained in war. At least some of the cost of food and lodging was deducted from soldiers’ pay, however, and they had to purchase their own equipment, which would have been an expensive initial outlay. Legionaries were not allowed to marry, though informal relationships were common.

One plaque of a diploma dating from AD 88, granting citizenship to a Roman auxiliary soldier and his descendants, issued during the reign of the emperor Domitian. Military diplomas like this often became treasured family possessions and were handed down through several generations. (Sepia Times/UIG via Getty Images)

Legionary service was hard and dangerous. In the 1st century AD, legionaries could expect to spend their entire career on campaign or in a garrison far from home, and they constantly faced the prospect of being wounded or killed in battle. Legionaries were often tasked with major construction projects, such as building forts and roads, which involved tough physical labour. They were also subject to strict rules and harsh discipline: punishment could include beatings and even death for serious crimes. The legions would have drawn the majority of their recruits from poorer, mostly unskilled urban citizens, for whom an arduous military life was an attractive alternative to one of irregular employment and potential poverty.

Roman auxiliary soldier

Mons Graupius, AD 83

The Roman auxiliary infantryman is about 25 years old. He has been in Britain for seven years, since he was recruited in his Batavian homeland in the Rhine delta and sent as a reinforcement to cohors IX Batavorum. He has participated in all of Agricola’s campaigns in northern Britain. He has been fighting for several minutes so he is hot under his helmet and armour, and he is sweating and wet from the drizzly rain that has been falling all morning. His feet and lower legs are covered in thin, black mud from walking across peat bogs on the moorland, and his face, right hand and arm are spattered with blood. He is in the front rank of his century, which has engaged a band of Caledonian warriors. He has just punched an enemy warrior in the face with the boss of his shield and is about to stab him in the stomach with his short sword.

Weapons, dress and equipment

This infantry soldier has already thrown his two hastae, and is now fighting with his short, sharply pointed sword (gladius; 1), designed for stabbing rather than cutting; and his flat, oval shield (scutum; 2), which has a metal boss (umbo) in the centre, covering a horizontal handgrip. He uses the shield as a weapon as much as a means of defence: he can punch his enemy in the face with the metal boss, or shove him aside with his shoulder against the board. The back of the boss is filled with wool and horsehair to protect his knuckles. If he loses or breaks his sword, he will use his wide-bladed dagger (pugio; 3) as a back-up weapon.

His copper-alloy helmet (galea; 4) has an extension at the back to cover his neck and a reinforcement on the brow to deflect downward sword cuts. Hinged cheek pieces, with scallops around the eyes and mouth, protect his face. His ears are also uncovered so he can still see, hear and communicate with those around him. Over a thick, woollen tunic (tunica; 5) he wears a lorica hamata (6), which is made from small, interlocking iron rings. At around 9kg, it is heavy but very flexible and covers his torso, abdomen and groin, and gives excellent protection against cuts and thrusts from any angle. In the cold and wet of northern Britain he is grateful for his woollen breeches (braccae; 7), and his closed leather boots (caligae; 8), which have iron studs nailed into the soles to give some much-needed grip on the muddy ground.

Roman soldiers were fond of personal ornament. This auxiliary infantryman is no exception: his sword and dagger scabbards are beautifully, though cheaply, decorated; his crossed belts (baltei; 9) are covered in embossed plates, which have been coated in tin to give them a ‘silver’ appearance; and he sports an impressive ‘apron’ of studded leather straps (10) that jingles when he moves.

The conquered territories that made up the provinces of the Roman Empire paid taxes in the form of money, raw materials and agricultural commodities, and they also had to provide their share of men for the auxiliary units of the Roman Army. These auxiliary units were made up of a mixture of volunteers and conscripts. Auxiliaries could look forward to a similar life to their legionary counterparts, albeit with lower pay. From the reign of the emperor Claudius, however, after 25 years’ service auxiliary soldiers could be granted citizenship for themselves and for their children. This was a significant incentive and must have been an important attraction that greatly increased the number of volunteers.

The provision of young men for the Roman Army could be a burden on provincial communities, particularly those with a predominantly rural population. The Batavi, a tribal group who lived in a small area of the Rhine delta, had a special treaty relationship with the Roman Empire, and were exempt from all taxes except for the supply of men to serve in the Army. This was partly in recognition of Batavian loyalty in earlier campaigns in the region but also because the Romans believed the Batavi made particularly good soldiers, renowned for their ability to swim in full armour, and cross rivers that were impassable to other troops. In his comprehensive study of the Roman auxiliaries, the historian Ian Haynes describes (2013: 112–16) the enormous contribution made by the Batavians to the Roman Army: in the 1st century AD the Batavi provided eight cohorts (auxiliary units of infantry or mixed infantry and mounted soldiers) and one ala, as well as imperial bodyguards and sailors. This may have been as many as 5,500 men at any one time, from a total community of perhaps only 30,000–40,000 people.

On top of the chance of citizenship, for the young men of the Batavi the Roman Army held additional attractions. Warfare was a major part of Batavian life, and martial skills and arms and armour were highly valued; burials of Batavian men contained weapons long after the practice was abandoned elsewhere. The equipment of an auxiliary infantryman or cavalryman in the Roman Army – a metal helmet; armour made from iron ‘mail’ or scales; a sword, shield and spear – was that usually associated with an elite warrior or chief; enlisting in the Roman Army would have given Batavian youths enhanced status immediately. Even accepting these attractions, however, such a large contribution of manpower from a small community could not have been achieved without conscription. To begin with, the Batavian nobility pr...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Table of Contents

- Introduction

- The Opposing Sides

- Caratacus’ Last Stand

- The invasion of Mona

- Mons Graupius

- Analysis

- Aftermath

- Bibliography

- eCopyright