eBook - ePub

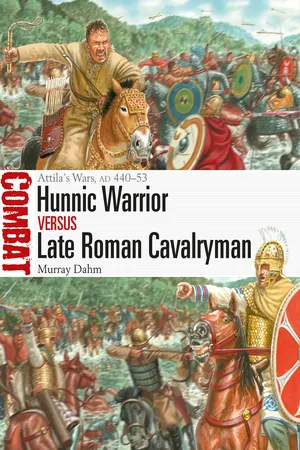

Hunnic Warrior vs Late Roman Cavalryman

Attila's Wars, AD 440–53

- 80 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Roman and Hunnic fighting men are assessed and compared in this fully illustrated study of Attila's bid to conquer Europe in the 5th century AD.

The Huns burst on to the page of western European history in the 4th century AD. Fighting mostly on horseback, the Huns employed sophisticated tactics that harnessed the formidable power of their bows; they also gained a reputation for their fighting prowess at close quarters. Facing the Huns, the Roman Army fielded a variety of cavalry types, from heavily armed and armoured clibanarii and cataphractii to horse archers and missile cavalry. Many of these troops were recruited from client peoples or cultures, including the Huns themselves.

After carving out a polyglot empire in eastern and central Europe, the Huns repeatedly invaded Roman territory, besieging the city of Naissus in 443. With Constantinople itself threatened, the Romans agreed to pay a huge indemnity. In 447, Attila re-entered Roman territory, confronting the Romans at the battle of the Utus in Bulgaria. The Huns besieged Constantinople, but were unable to take the city. In 451, after Hunnic forces invaded the Western Roman Empire, an army led by the Roman general Aetius pursed the invaders, bringing the Huns to battle at the Catalaunian Plains.

Featuring specially commissioned artwork and maps, this study examines the origins, fighting methods and reputation of the two sides' cavalry forces, with particular reference to the siege of Naissus, the battle of the Utus and the climactic encounter at the Catalaunian Plains.

The Huns burst on to the page of western European history in the 4th century AD. Fighting mostly on horseback, the Huns employed sophisticated tactics that harnessed the formidable power of their bows; they also gained a reputation for their fighting prowess at close quarters. Facing the Huns, the Roman Army fielded a variety of cavalry types, from heavily armed and armoured clibanarii and cataphractii to horse archers and missile cavalry. Many of these troops were recruited from client peoples or cultures, including the Huns themselves.

After carving out a polyglot empire in eastern and central Europe, the Huns repeatedly invaded Roman territory, besieging the city of Naissus in 443. With Constantinople itself threatened, the Romans agreed to pay a huge indemnity. In 447, Attila re-entered Roman territory, confronting the Romans at the battle of the Utus in Bulgaria. The Huns besieged Constantinople, but were unable to take the city. In 451, after Hunnic forces invaded the Western Roman Empire, an army led by the Roman general Aetius pursed the invaders, bringing the Huns to battle at the Catalaunian Plains.

Featuring specially commissioned artwork and maps, this study examines the origins, fighting methods and reputation of the two sides' cavalry forces, with particular reference to the siege of Naissus, the battle of the Utus and the climactic encounter at the Catalaunian Plains.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Hunnic Warrior vs Late Roman Cavalryman by Murray Dahm,Giuseppe Rava in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & European History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

The Opposing Sides

ARMY COMPOSITION AND SIZE

Hunnic

For many aspects of Hun culture we are hamstrung by our sources which, although plentiful, are often fragmentary and do not provide modern historians with the level of detail we would prefer. Often our sources’ information is vague or inaccurate (where we can tell) and, even when a source was in a position to give us precise details – such as Cassiodorus, Olympiodorus or Priscus, who were all sent on embassies to the Huns – they often do not satisfy our modern requirements. They are all we have, however, and although aspects of archaeology continue to add to our knowledge, we must use what we have to our best ability.

Several sources refer to the custom of skull elongation among the Huns. It was possibly a practice among those of high status. Sidonius describes (Carmina 2.246–47) the heads of the Huns as great round masses rising to a narrow crown. Shown here is an Afrasiab skull from AD 600–800 in the Afrasiab Museum (Afrosiyob-Samarqand shahar tarixi muzeyi), Samarkand, Uzbekistan. (Jona Lendering/Wikimedia/CC0)

Jordanes tells us (Getica 182) that just before the battle of the Catalaunian Plains, Attila’s army numbered 500,000 men. No modern authority comes close to believing such a figure (although Syvänne uses it). This massive number is, however, also consistent with the huge losses attributed to the Catalaunian Plains fighting: 165,000 in Jordanes (Getica 217), 300,000 in Hydatius (Chronicle Olympiad 308/28) and 180,000 in Paul the Deacon (Historia Romana 14.6). When the Goths crossed the Danube in 376, we are told by Eunapius (Historia F42) that they numbered 200,000 men. John Malalas states (Chronicle 358/14.10) that Attila had many tens of thousands of men, so too the Chronicon Paschale (Olympiad 307, 450). The purpose of these numbers is to emphasize the overwhelming horde-like nature of these enemies. There are many losses to the Huns that are only hinted at in the sources, but defeat seems to have been a common feature. Luckily for the Romans, they could always purchase peace with gold – but the price was ever increasing.

We find other observations in the ancient sources that may be useful for estimating the strength of the Huns in general terms. Ammianus describes (Res gestae 31.2.21–22) the Halani as being similar to the Huns, growing up in the saddle: all men were warriors and they delighted in danger and war. This picture is confirmed by Sidonius (Carmina 2.262–70), although in somewhat poetic terms: he tells us that Hun children were born for battle, and scarcely had they learned to stand, they were put on the back of a horse. Whatever the numbers of men, women and children involved in Hun migrations, it is probable that male children were inducted into warfare relatively early and probably continued to fight for many years. Skill in archery was clearly taught from a young age and maintained. Although we lack detail about the Huns, earlier cultures enrolled boys young and the ages of military service were often assumed to span the years from 18 to 60, but there are exceptions both younger and older. For some commentators, the number of 200,000 or 500,000 represents the entire people of Huns or Goths and so, in terms of fighting men, the number would be considered slightly below half of that. Even so, those are still massive numbers of men to move, feed and coordinate on a battlefield and other historians bring the estimates of manpower down lower still.

This portrait of the Alchon Hun king Khingila (r. 440–90), a contemporary of Attila’s, on a Hunnic coin clearly shows skull elongation. Ammianus, Jordanes and others also refer to cheek scarring among Hunnic males, but there is no evidence of this in such portraits and other depictions. Jordanes tells us that the Huns possessed the ‘cruelty of wild beasts’ (Getica 128) and cut the cheeks of their males with a sword to inure them to wounds. Ammianus records (Res gestae 31.2.2) that at birth the cheeks of the males are marked by an iron. Thus, they did not grow beards and, as Jordanes tells us, ‘are short in stature, quick in bodily movement, alert horsemen, broad shouldered, ready in the use of bow and arrow, and have firm-set necks which are ever erect in pride’ (Getica 128). Others such as Jerome (Commentary on Isaiah 7:20–21) fixate on this supposed facial cutting and the inability of the Huns to grow beards. (PHGCOM/Wikimedia/CC BY-SA 3.0)

The entries of Prosper in his Epitoma Chronicon that mention Attila and the Huns are often brief, although they present fascinating summations of our information. Prosper records (Epitoma Chronicon a.451) that, after Attila killed Bleda and forced his brother’s people to submit to him, he was thus strengthened by the resources of the deceased Bleda, and Attila forced many thousands of the neighbouring peoples into war. Prosper praises the foresight of the Roman general Aëtius in 451 in gathering a force of allies hurriedly collected from everywhere that matched the numbers of the Huns. This praise implies that indeed, the Huns usually outnumbered any force the Romans could muster against them. Although modern scepticism towards ancient sources is useful, especially with regard to numbers, every source mentions the huge numbers of men at the Catalaunian Plains so, perhaps, we should entertain the possibility that there were indeed huge numbers involved. More than that, if an unprecedented alliance was needed to match the Huns’ numbers at the Catalaunian Plains, it is not difficult to imagine that the Huns nearly always outnumbered their Roman opponents in previous battles.

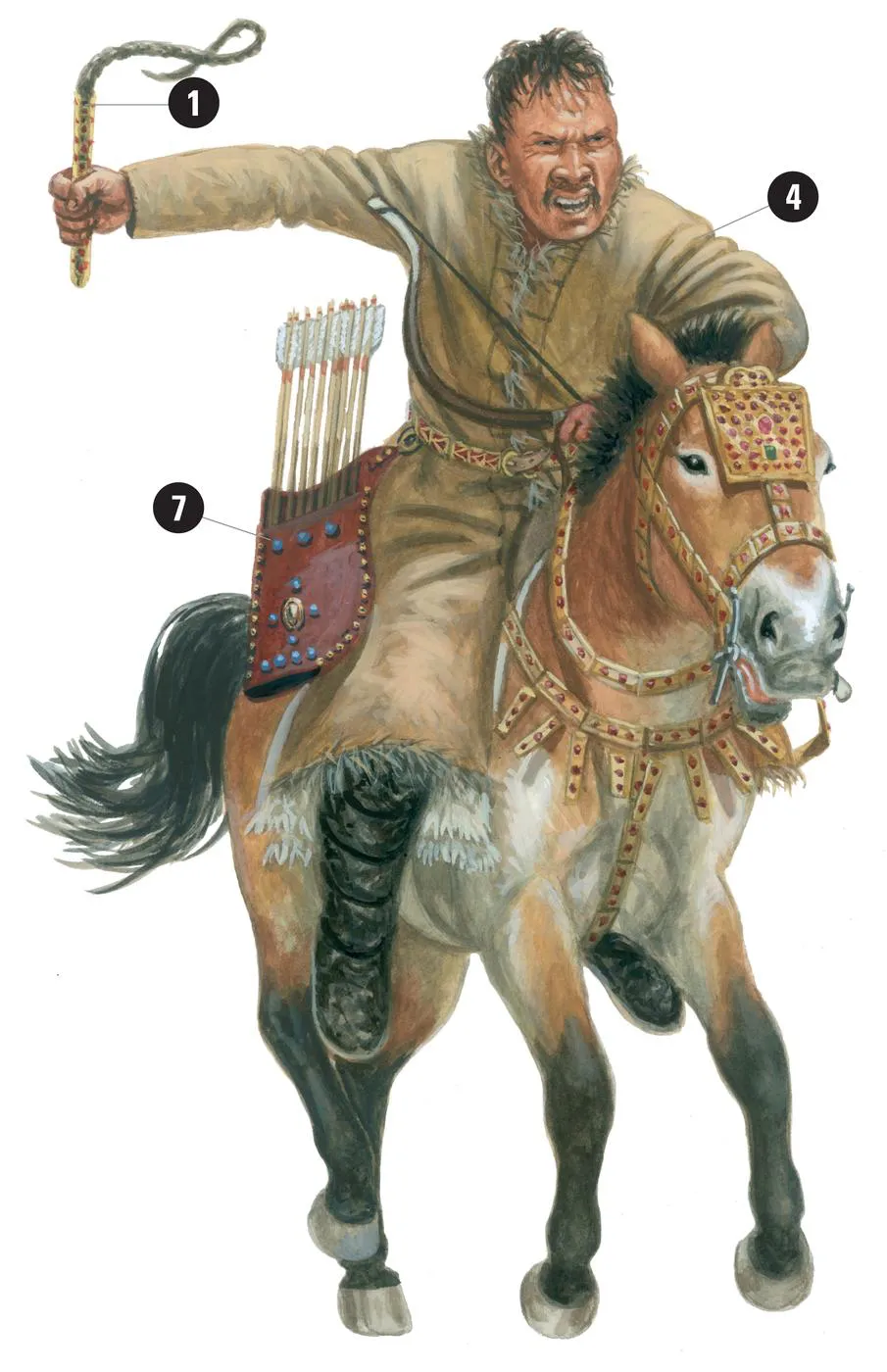

Hunnic warrior

Naissus, AD 443

Riding a Takhi horse with its characteristic short mane and tail, a young Hunnic aristocrat cavalryman charges towards the breached walls of Naissus in 443. The Hunnic siege platforms, rams and ladders have done their work and the city lies open. Eager to prove his worth to his fellows, he leads the apparently reckless charge from the front.

Weapons, dress, and equipment

Our cavalryman rides with his bow and reins in his left hand and flourishes his horsewhip (1), used to control his horse in the absence of spurs, in his right hand. He is armed with a composite bow (2) and a spatha (3) – taken from a fallen foe – at his left side. He wears a thick tunic (4), and typical boots (5), and a belt (6) made of gold and decorated with garnets. He is equipped with a bowcase quiver (7), unusually on his right hip.

His head shows evidence of skull elongation, practised by aristocratic and royal families among the various peoples of the Huns. He also shows the beginnings of a moustache; the inability of the Huns to grow beards was a trait remarked upon in the sources. Our sources record that Hun cavalry charges appeared chaotic (at least to Roman eyes) until the last moment when the disparate groups of cavalry ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Table of Contents

- Introduction

- The Opposing Sides

- Naissus

- The Utus River

- The Catalaunian Plains

- Analysis

- Aftermath

- Bibliography

- eCopyright