![]() PART ONE: ANTECEDENTS

PART ONE: ANTECEDENTS![]()

1.

SLAVERY • • • “don’t nobody know my name but me”

WE RAISE THE WHEAT, DEY GIB US DE CORN;

WE BAKE DE BREAD, DEY GIB US DE CRUST;

WE SIF DE MEAL, DEY GIB US DE HUSS;

WE PEAL DE MEAT, DEY GIB US DE SKIN;

AND DATS DE WAY DEY TAKES US IN.

WE SKIMS DE POT, DEY GIB US DE LIQUOR,

AN’ SAY, “DAT’S GOOD ENOUGH FER A NIGGER.”

—ANONYMOUS

NO MASTER COULD BE THOROUGHLY COMFORTABLE AROUND A SULLEN SLAVE; AND, CONVERSELY, A MASTER, UNLESS HE WAS UTTERLY HUMORLESS, COULD NOT OVERWORK OR BRUTALLY TREAT A JOLLY FELLOW, ONE WHO COULD MAKE HIM LAUGH.

—W. D. WEATHERFORD AND CHARLES S. JOHNSON

THE LINE THAT LEADS TO MOMS MABLEY, NIPSEY RUSSELL, BILL COSBY, AND MYSELF CAN BE TRACED BACK TO THE SOCIAL SATIRE OF SLAVE HUMOR, BACK EVEN THROUGH MINSTRELSY, THROUGH COUNTLESS ATTEMPTS TO CAST OFF THAT FANTASY.

—GODFREY CAMBRIDGE1

I

Something peculiar happened on the way to the New World—or, at least, very shortly afterward. Somewhere between their departure from West Africa’s shores and the early stages of their arrival as human chattel in the Americas, the African captives transported across the Atlantic underwent a subtle but far-reaching and remarkable psychological transformation.

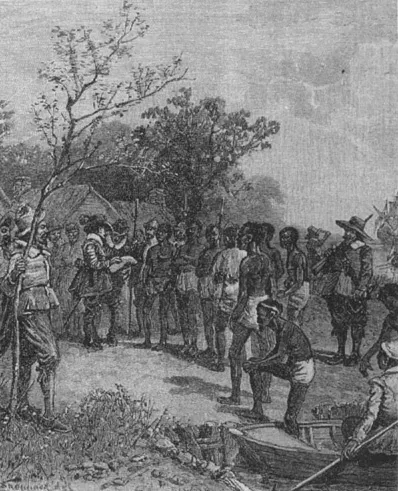

It may have begun aboard one of the large canoes that snaked along the winding Gambia or Senegal rivers, stopping periodically to take on more human cargo and then moving away from the dense interior toward Africa’s western coast. It could have been there that it first took form in the minds of some of those captives as, bound and yoked together in coffles, their destiny now almost certain, they were transported from the familiarity of tribal life to an ominous if, to them, yet unknown fate. Or it may have occurred later, when branded and fettered and, no doubt, still baffled and dismayed, they waited in cattlelike stockades or slave pens at ports such as Britain’s Cape Coast Castle on the Gold Coast or the infamous Maison des esclaves on Gorée Island off the coast of Senegal. At these and similar sites, “tens of millions of Africans” were estimated to have last touched their own soil before being forcibly transported overseas.2

Or perhaps it happened later, during the Middle Passage (the treacherous three- to twelve-week voyage to the New World), as, surely terrified by now, they lay shackled and longing either for the fraternity of their homelands, or more realistically for a merciful death in the dank, cramped bowels of those typically overcrowded slave vessels; it may have even occurred during the brief daily intervals when male captives were joined with females on the ships’ decks to momentarily glimpse daylight, exercise in order to restore their throttled circulation, and ceremoniously entertain their captors. Or it might have surfaced even later, at auction blocks in the West Indies or America, as they were prodded, inspected, and bargained over by prospective buyers, or subsequently when, having been duly purchased and dispatched to their owners, they first began their assigned labor on the farms and plantations to which most would be confined for the rest of their lives.

It is nearly impossible to determine exactly where and when it happened—few confirmed testaments of the thoughts of these African captives were sought or recorded during the three and a half centuries of the trans-Atlantic slave trade. Indeed, initially very few slaves could converse or write in the language of their European captors, and it is doubtful, given the express purpose of the endeavor, that their captors would have heeded any such expressions.

But during their transformation from Africans to African-American slaves, a remarkably resilient and inventive manner of behaving and observing both themselves and the external world began to emerge. It would be nurtured and shaped by their interaction with America’s social customs and the “peculiar institution” of slavery, be passed on to subsequent arrivals and, eventually, become a key factor in African America’s rich and expansive under- or subculture. As one historian put it: “Herded together with others with whom they shared only a common condition of servitude and some degree of cultural overlap, enslaved Africans were compelled to create a new language, a new religion, and a precarious new lifestyle.” Later, that black lifestyle or subculture would become quite probably the most formidable influence on American popular culture.3

It is in music, of course, that this impact has been most significant. There is also plentiful evidence of the impact on, among other pursuits, dance, sports, colloquial speech, and fashion. But it is the expressive manner of African-American humor that, second to music, has most influenced mainstream America’s popular culture. And although bondage and oppression hardly seem to favor the development of a comic tradition, slavery was, ironically, the primary factor in molding the style and content of both private and public black humor. From the beginning it combined cultural elements of traditional African societies with the new language, social institutions, and behavioral patterns of antebellum America. Since then it has taken a course that is as labyrinthine, ironic, and melodramatic as the work of some of our most darkly inventive Southern Gothic fiction writers.

What might have been going through the minds of those African captives when they arrived in the Americas?

Some, no doubt, still entertained thoughts of escaping or destroying themselves. The recorded instances of suicides, attempted breakaways, and rebellions attest to the numbers who chose death or the slimmest opportunity for freedom over the safety of serfdom. At the height of the transatlantic trade, epidemics, futile escape attempts, and suicides claimed 6 to 25 percent of the captives; the British Privy Council, after examining records of slave ships, concluded that, on the average, of the African captives who began the Atlantic journey, 12.5 percent perished.4

Statistics, however, convey little of the reality. The story related by a South Carolina black man who had endured the Middle Passage offers a more vivid description:

Dey been pack in dere wuss dan hog in a car when dey shippin’ ’em. An’ everyday dem white folks would come in dere an’ ef a nigger jest twist his self or move, dey’d cut de hide off him wid a rawhide whip. An’ niggers died in de bottom er dat ship wuss dan hogs wid cholera. Dem white folks ain’ hab no mercy. Look like dey ain’ known wha’ mercy mean. Dey drag dem dead niggers out an’ throw ’em overboard. An’ dat ain’ all. Dey th’owed a heap er live ones wha’ dey thought ain’ guh live into de sea.5

In addition, there were numerous reports of insurrections and suicides, sometimes before the slave vessels ever left port. According to the captain of the British ship Hannibal:

Negroes are so wilful and loth to leave their own country, that they have often leap’d out of the canoos, boats and ship, into the seas, and kept under water till they were drowned to avoid being taken up and saved by our boats, which pursued them; they having a more dreadful apprehension of Barbadoes than we have of hell....”6

Other less obstinate Africans undoubtedly initially consoled themselves with the thought that the servitude they faced in America would be similar to what many of them had seen or experienced directly in tribal Africa. Slavery, after all, had existed in Africa since recorded times, although major slave regimes, especially in the west, were “relatively few and of limited longevity in the period prior to the arrival of the Christian Europeans.” As in Europe, domestic servitude was common in most of the early, more complex African societies, and caravan routes across the Sahara Desert had facilitated Africa’s commercial export of slaves to the Mediterranean area even before the emergence of the Roman Empire.7

After the onset of the trans-Atlantic trade, commercial use of slaves within the African interior increased. And more African states, reacting to the European demand for slaves, resorted to intertribal warfare and detainment of criminals as a means of acquiring the human chattel that was fast becoming Africa’s chief export. Still, slaves or “wageless workers” in the inland regions of Africa, which were generally isolated from Muslim and eventual European influences, functioned primarily within a comparatively amiable system. They were “seldom or never men without rights or hope of emancipation” and were not “outcasts in the body politic,” writes the British historian Basil Davidson. “On the contrary they were integral members of the community. Household slaves lived with their masters, often as members of the family. They could work themselves free of their obligations. They could marry their master’s daughters. They could become traders, leading men in peace and war, governors and sometimes even kings.”8

So despite the suicides, insurrections, and barbaric conditions of the Middle Passage, some African captives must have clung to the hope that the treatment awaiting them in the Americas would be less hostile and dehumanizing than what they had experienced since their capture. Those who arrived anticipating a system of bondage even remotely resembling the comparatively benevolent form that some had experienced in the interior of their homeland, however, were quickly and bitterly disappointed. What they actually found was what Davidson describes as a “deep soil of arrogant contempt for African humanity.” That contempt was quite possibly the most destructive consequence of the transatlantic slave trade.9

Africans dispatched to the New World found themselves in a perplexing if not devastating position. The possibility of successfully escaping and returning to their native land was practically nonexistent. And they faced not only a cruel and, for the most part, inflexible system that governed practically every aspect of their lives, but also a community of people who placed little or no value on their humanity. What were they to do?

Some, overwhelmed and sensing the futility of any type of resistance, quite probably succumbed to melancholy and despair and dolefully submitted to the status of mere chattel—becoming, in effect, Uncle Toms, harmless darkies, or Sambos. As the historian Stanley M. Elkins has suggested, these slaves, like many concentration camp victims in the 1940s, accepted their dependent status and internalized the social role demanded of them by their masters. But Sterling Stuckey and numerous other historians have pointed out that many others avoided “being imprisoned altogether by the definitions the larger society sought to impose.” They neither desperately sought an immediate, violent solution to their condition nor entirely capitulated psychologically; instead, they chose deception and subterfuge as a primary survival tactic.10

“The first line of defense for any vanquished or occupied nation, as for any camp of war-prisoners,” writes James Pope-Hennessy, “is calculated cunning and deceit.”11

Accordingly, many slaves adopted an obsequious social mask as an essential survival apparatus. “Slaves who behaved like Sambos,” contends Ronald T. Takaki, “might not have actually been Sambos, for they might have been playing the role of the loyal and congenial slave in order to survive. . . . Sambo-like behavior may have been not so much a veil to hide inner emotions of rage and discontent as an effective means of expressing them.” In effect, this behavior may have demonstrated “resistance to efficiency, discipline, work, and productivity. Where the master perceived laziness, the slave saw refusal to be exploited . . . the same action held different meanings, depending on whether one was master or slave.”12

To maintain respect for themselves or preserve any remnants of their native culture, subterfuge and lying were absolutely necessary for the Africans brought to America’s shores. In addition to the primary tasks of tilling the fields of cane, cotton, and tobacco plantations and providing domestic and skilled craft services, survival in the New World depended to a great extent upon appeasing slaveholders’ demands for an ingratiating demeanor and the eradication of nearly all vestige of Africanisms.

The response of most blacks to these demands was both rational and effective. As one social historian puts it: “Over many generations the slave developed techniques of deception that were, for the white man, virtually impenetrable.” Numerous comments from slaveholders or white observers affirm the existence as well as the effectiveness of black duplicity: “So deceitful is the Negro,” one explained, “that as far as my own experience extends I could never in a single instance decipher his character.. . . We planters could never get at the truth.” Another claimed: “He is never off guard. He is perfectly skilled at hiding his emotions. . . . His master knows him not.”13

Obviously, the pragmatically adopted policy of “puttin’ on massa” and thereby making deceit part of their lifestyle had negative long-term consequences for slaves and their descendants. But it did solve some immediate problems presented by bondage. Slaves also used subversion and sabotage—work delay, theft, arson, and destruction of crops—as a means of resistance. In addition, they often feigned ineptitude and ignorance to achieve their own ends.

The dynamics of this strained interaction, with its contradictory goals and clandestine motives—a methodically fashioned maze of non-communication and misdirection from the black perspective—are largely responsible for the convoluted interpersonal relationship of black and white Americans to this day. The reaction of one Louisiana physician to slave duplicity and subversiveness not only points out the extent to which slaves duped many of their masters but, in retrospect, is also quite humorous. In the mid-ninetenth century Dr. Samuel Cartwright wrote an essay on diseases peculiar to the Negro, among them, DYS-AESTHESIA AETHIOPICA:

From the careless movements of the individuals affected with this complaint they are apt to do much mischief, which appears as if intentional, but is mostly owing to the stupidness of mind and insensibility of the nerves induced by the disease. Thus they break, waste, and destroy everything they handle; abuse horses and cattle; tear, burn, or rend their own clothing. . . . When driven to labor by the compulsive power of the white man, he performs the task assigned to him in a headlong, careless manner, treading down with his feet or cutting with his hoe the plants he is put to cultivate; breaking the tools he works with, and spoiling everything he touches that can be injured by careless handling.14

The chicanery and deception established in the initial contacts between black slaves and white masters added a note of comic absurdity and dissemblance that, as one would expect, still surfaces frequently in jokes about interracial confrontations emerging from the African-American community. For instance, there is the tale of a black maid who worked in a home near an Army camp during World War II. Her employer, displeased with her work, asks: “D...