eBook - ePub

A Fractured Landscape of Modernity

Culture and Conflict in the Isle of Purbeck

J. Wilkes

This is a test

Share book

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

A Fractured Landscape of Modernity

Culture and Conflict in the Isle of Purbeck

J. Wilkes

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This book uses the contradictions, fractures and coincidences of a twentieth-century rural landscape to explore new methods of writing place beyond 'new nature writing'. In doing so it opens up new ways of reading modernist artists and writers such as Vanessa Bell, Mary Butts and Paul Nash.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is A Fractured Landscape of Modernity an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access A Fractured Landscape of Modernity by J. Wilkes in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Arte & Fotografía. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

ArteSubtopic

Fotografía1

Studland Beach

Introduction: Triangulating a coast

Seven o’clock on a winter evening. Steel shrouds ringing against masts from the massed boats in Mitcham’s yard and the yacht club. Turks Lane flooded again, and rain on the roof of the scout hut, where in the back room a group of boys have compasses, protractors and photocopied pages of a map on the table. Projected in their imaginations to a boat off a rocky coastline, they measure the angles and draw intersecting lines from a chapel and a coastguard cottage. The third line extends south-east from a rock stack: the pencil traces over the blankness of the sea, and passes through the “X” of its fellows.

You need to take the bearings of three points to do a resection or, as it is often called, a triangulation. Two lines will cross to give you the location, and the third crossing confirms it. Imagine yourself thrown up as a stranger on an unfamiliar shore, as Paul Nash imagined his reader thrown up by the waves on the beach at Swanage.1 You have no idea where you are. You pick three landmarks. Triangulate them, cross them.

I am walking the beach at Studland. This is not an unfamiliar shore – in fact, its very familiarity is the problem. But this is a research trip: I am here to take bearings. The first point is up ahead, beyond the rows of beach huts boarded up for the winter. Dark creosoted wood, damp in the clear light, and the vernacular texture of corrugated iron and asphalt roofing. Each with a neat National Trust number tacked to its front, these summer shelters are set back into the dunes in short terraces, near where Middle Beach ends in the iron-stained sandstone cliffs of Redend Point.

Figure 1.1 Anti-tank obstacles at Studland Beach, 2008

Behind the huts, a stream has cut a gully. Here, where the gradient is gentler, a path leads up towards private land, and strung all across this little valley are large concrete blocks, set into the ground a few feet apart, each one rising to a pyramid (Figure 1.1). Echoing the terraces of the beach huts, these tank traps, poking out of the dead bracken, are permanent reminders of the militarised beach of 70 years ago, when Studland was considered one of the two areas of Dorset coastline most vulnerable to invasion, and fortified accordingly with beach obstacles, pillboxes and minefields.2

Forty years earlier still, before the concrete, steel and explosives, this beach was considered to be an unspoiled example of coastal scenery; according to one guidebook author at the turn of the century, Nature – with a capital N – had ‘kindly set a great gulf between Studland and modernity’.3 Thus described, Studland becomes the kind of place that might well be sought out by ‘anti-trippers’, as another guidebook had termed those, back in 1884, who were ‘the pioneer[s], ever on the look-out for fresh sands and billows new, [ ... ] driven away and away by railways and “trippers” ’.4 Perhaps such vanguardist ambitions encouraged members of the Bloomsbury group to holiday in Studland in these years: Vanessa Bell visited for at least three years in succession from 1909, accompanied variously by friends, her growing family, and an assortment of nurses and pets.5 The traces of these seaside gatherings are still visible in Bell’s collection of holiday photographs in the Tate Archives (Figures 1.2, 1.3 and 1.4), and in her famous painting of circa 1912, Studland Beach (Figure 1.5). These three objects – a painting, a set of holiday snaps preserved in the archives, and a row of concrete blocks – bring together three apparently unconnected narratives, as the social history of the beach and its architecture of leisure, the ideas and practice of a particular kind of Post-Impressionism, and the effects of the technology of mechanised warfare converge on a few hundred metres of coastline. At a finer level still, they converge in the coincidental repetition of one particular shape, a cube surmounted by a pyramid. In the face of coincidence it is always possible, of course, to appeal to necessity; but these shapes are as much accidents of design as they are features. To dismiss coincidence in this way is to fail its potential. Instead, this chapter aims to exploit it, by treating these congruent elements as a matrix, a support or frame of sorts on which to hang a narrative exploration of what constitutes a landscape. In the case of Studland beach, it is constructed from the tangled threads of war, leisure and aesthetics.

Figure 1.2 Vanessa Bell, ‘Photograph of Clive Bell and Virginia Woolf on the Beach at Studland Bay, Dorset, 1910’

Source: London, Tate Archive, TGA 9020/1. Copyright Tate, London 2013.

Figure 1.3 Vanessa Bell, ‘Photograph of Virginia Woolf and Clive Bell on the Beach at Studland Bay, Dorset, 1910’

Source: London, Tate Archive, TGA 9020/1. Copyright Tate, London 2013.

Figure 1.4 Vanessa Bell, ‘Clive Bell, Desmond MacCarthy, Marjorie Strachey, Molly MacCarthy at Studland, 1910’

Source: London, Tate Archive, TGA 9020/1. Copyright Tate, London 2013.

First line: The use of the beach

Bell’s Studland snapshots provoke my memory in a strange way, bringing to mind as I look at them not an episodic recall of my own childhood days spent at this beach, but a sympathetic resonance with the poses and the bodies recorded in the photographs. I feel as if my own legs were extended for balance down a sloping dune, sense the spread of errant grains across clothing and inside it, and know >again the prickle of the stems of marram grass and dead gorse that are buried in that loose adulterated sand.

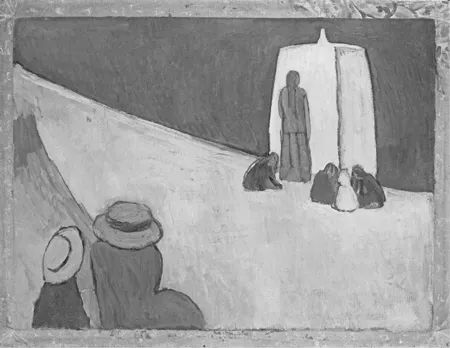

Figure 1.5 Vanessa Bell, Studland Beach, c.1912, oil on canvas, 76.2 × 101.6 cm

Source: London, Tate Gallery. Copyright Estate of Vanessa Bell, courtesy Henrietta Garnett/Copyright Tate, London 2013.

What makes this sense of familiarity so strong and irresistible? Perhaps that the photographs of Clive Bell and Virginia Stephen show a recognisably modern holiday scene, if one that is daring for its time: a man and a woman baring their legs and arms to the sun and the surf, their poses relaxed and unencumbered by social formalities. It tempts one into anachronism, as if beach life were a 100-year eddy in time that could yoke together then and now in a common celebration of the delightful effects of waves on sand. But that impression needs to be scrutinised: other photos in the album reveal the presence of the Bell’s perambulator and nurse, the domestic paraphernalia and labour relations of upper-middle-class Edwardian life transported wholesale to a beach which, even if its dominant orientation of longing is out towards the flat horizon line, is in truth never freed from its vertical axis of social and economic stratification.

From its very inception, the seaside holiday was intimately linked to the pursuits of the leisured gentry. One such was the Reverend William Clarke, a pioneering beach-goer who recorded as early as 1736 that he was spending his summer in Brighton bathing in the sea, horse riding and viewing the remains of Saxon camps.6 And yet, as Alain Corbin has suggested, such relative spontaneity was quickly overtaken by a system of therapeutic and regulated bathing, and behaviour like the Reverend’s was quickly subdued.7 The strict codes and rituals of inland spas like Bath or Tunbridge Wells were transferred to the newly fashionable seaside locations,8 as new modes of behaviour, destructive or defensive of the norms of privacy and social distance, were stimulated by the beach’s unique topography of exposure.

The metaphor of struggle is apt, as far from being a peaceful escape from the pressures of everyday life, the beach has long been an arena where two related battles took place: firstly the fight to establish as a site of leisure what was previously a site of maritime labour, such as fishing, salt-making, and seaweed-gathering (or, as in Turner’s picturesque etchings, of subversive activities like smuggling and salvage that denied claims of personal and national property);9 and secondly to regulate the newly fashionable pleasures of bathing in the name of morality and propriety. A battle of the first kind had taken place in Swanage, Studland’s closest neighbouring town, over the preceding half-century, and its progress can be tracked through guidebooks published from the 1850s onwards. Philip Brannon’s Illustrated Historical and Picturesque Guide to Swanage and the Isle of Purbeck, published in 1858, indicates that the rapid transition Swanage was undergoing from working port to leisure resort was not without resistance: he warned the visitor arriving ‘by way of steamer from Poole’ to be ‘prepared to meet on first landing a frown from the genius loci in the form of the “bankers” of stone which the merchants of the place are perhaps compelled to preserve until they have better arrangements for shipping their merchandize’.10 These “bankers”, the piles of unshipped stone which the stone merchants would accumulate on the seafront, formed a defensive wall which the prospective “improvers” of Swanage needed to breach, but the roads too bore the marks of the town’s working identity: Brannon wrote that ‘the narrow roadway; worn into deep ruts with the farmers’ waggons, sending up clouds of dust as they descend with their loads of stone to the bankers; forcibly calls for modes of transport more consistent with the advance of science and business in our own day’.11 In E.D. Burrowes’s Sixpenny Guide to Swanage, published 20 years later, the quarrymen’s bankers are still proving problematic to would-be tourists: these ‘huge heaps of hewn stone [ ... ] which, whilst awaiting shipping line the margin of the bay here, and in places raise an almost impenetrable barrier to the eye and foot, are indisputably a great eyesore’.12 By the time Clive Holland wrote his Gossipy Guide to Swanage and District in 1900 however, the transformation was almost complete: the town was ‘the favourite “rest place” of a whole host of notabilities – musical, literary, artistic and social’, and the author even encouraged ‘the local authorities to pause before destroying its individuality and converting its picturesque quaintness into a little Margate, or miniature Broadstairs’.13 Nevertheless, it is not the battle over contested uses of the beach, but the clash over morality that Bell’s photographs speak of most eloquently, with their backdrops littered with the outmoded matériel of an outflanked army: the last charge of the bathing machine.

One of these curious pieces of mobile architecture can be seen breasting the dunes behind Marjorie Strachey and Molly MacCarthy (Figure 1.4), and although this is an attenuated descendant of the mighty contraptions that simultaneously permitted and controlled access to the sea for a full 200 years, it nevertheless shares the essential features of its type: wheels for mobility, and a wood and canvas superstructure for protection (as can be seen in Figure 1.2). What these late manifestations of the bathing machine fail to show is the fullest flowering of canvas outriggers and screens. The models designed by Benjamin Beale, which had spread from the beaches of Margate and were already appearing in engravings of Scarborough by 1735,14 were equipped with collapsible canvas canopies known as “modesty hoods”, which descended over the water to the front of the machine to enable bathers to access the water without being seen by prying eyes. Thomas Rowlandson’s satirical cartoons, dating from the early nineteenth century, show the machines in their full glory, and exploit the erotic possibilities of this battle of wits, and the attendant possibilities of sexual humiliation, to full effect.

The battle between privacy and exposure was fought with the technological proxies of the screen and the telescope, at least in Rowlandson’s depictions of such scenes. Without an enforced distance between men and women, these technologies of disguise and discernment may never have received the emphasis they did. Yet as organised and therapeutic bathing displaced indigenous popular forms of bathing in which it was normal for men and perhaps also for women to swim nude, and to mix on the beach and in the waves, the segregation of the sexes became the rule.15 From the early 1800s onwards, mixed bathing began to be denounced as indecent, a change that John Travis relates to both the rise of the Evangelical movement, and to the increased practice of swimming (as opposed to static immersion), which brought men and women closer together in the water.16 Bathing machines and bathing wear became standardised, and nude and mixed bathing increasingly regulated by bye-laws, although the question of male nudity in the waves remained a contentious one, and revolts against the moralisers, as well as non-enforcement of the new l...