eBook - ePub

Double-voicing at Work

Power, Gender and Linguistic Expertise

J. Baxter

This is a test

Share book

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Double-voicing at Work

Power, Gender and Linguistic Expertise

J. Baxter

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This book reveals how 'double-voicing' is an inherent and routine part of spoken interactions within institutional contexts. Baxter's research shows that women use double-voicing more than men as a means of gaining acceptance and approval in the workplace. Double-voicing thus involves an interplay between power, gender and linguistic expertise.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Double-voicing at Work an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Double-voicing at Work by J. Baxter in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Betriebswirtschaft & Öffentlichkeitsarbeit. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

BetriebswirtschaftSubtopic

Öffentlichkeitsarbeit1

Double-voicing in Our Everyday Lives

Abstract: This chapter sets the scene for the rest of the book by presenting its purpose, theoretical framework and three interwoven lines of inquiry. These are, first, the extent to which double-voicing is associated with issues of power; secondly, the constitutive interrelationship of gender and double-voicing; and thirdly, how speakers who double-voice index linguistic insecurity and/or linguistic expertise. The chapter proposes that while double-voicing may be a relatively unfamiliar construct in some linguistic fields, it is a common and inherent part of everyday communication within many social, educational and professional contexts.

Keywords: conversational insecurity; double-voicing; gender; single-voicing

Baxter, Judith. Double-voicing at Work: Power, Gender and Linguistic Expertise. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014. DOI: 10.1057/9781137348531.0003.

Introducing double-voicing

(At the end of an academic conference in western Europe, the organiser walks onto the stage)

Sue: Listen, I am as keen to get to the bar as you are (laugh from audience), but I just want to say a few words of thanks to our speakers.

In the course of a working day, many of us will use double-voicing to interact with our colleagues, managers, students, clients, friends and family. In this example, Sue, the speaker suggests that her audience, the conference delegates, might be very keen to get to the bar where alcoholic drinks are sold. She realises that they are probably tired of back-to-back presentations, and says what she believes are in their minds. She shows linguistic expertise in using a double-voiced comment, which anticipates the likely thoughts of her audience and she makes a joke at their expense to bring them ‘on side’. The comment also shows some awareness of her audience’s cultural expectations: namely, that it is customary to drink alcohol at academic conferences; it is acceptable for women to drink alcohol; and that as a woman, she can crack a joke publicly about the delegates’ assumed desire to drink. This small comment indexes the speaker’s self-reflexive ability to enter the world of her audience as a way of building solidarity between herself as conference organiser and a hall-full of tired academics.

In this book I shall explore the diverse ways in which we use double-voicing within spoken interactions in our everyday social and professional lives. I shall propose that there are intricate relationships between the use of double-voicing in everyday talk at work, and the ways in which speakers are relatively positioned by power and gender within specific contexts. According to their ‘subject positioning’ (Davies and Harré 1990), individuals may or may not be able to draw upon double-voicing as a resource for linguistic expertise. The organiser above was actually a leading academic in the field of linguistics, and thus carried the status and authority to make jokes in collusion with her audience. I suggest that double-voicing can provide a rich understanding of the nuanced ways in which linguistic interactions are negotiated and identities are constructed within everyday settings in social and professional life.

For some linguists, the term ‘double-voicing’ may be unfamiliar, although it has a highly influential, if under-valued role in the history of Applied Linguistics and Sociolinguistics. The term is associated with the work of the Russian philosopher, Mikhail Bakhtin (1895–1975), who coined the phrase ‘double-voiced discourse’ in relation to the study of drama and fiction, and in particular to the novels of Dostoevsky. However, Bakhtin (1984: 194) was also acutely aware of the applications of double-voiced discourse to ‘the ordinary speech of our everyday life’, and he frequently made comparisons between quotidian speech and the language of academic discourse. In the context of this book, ‘double-voicing’ means that when a person speaks, they have a heightened awareness of, and responsiveness to, the concerns and agendas of others, which is then reflected in the different ways in which they adjust their language in response to interlocutors. This responsiveness goes well beyond normal conversational interactivity, and usually contains a ‘power’ dimension in that double-voicing can be used as a strategy to resist threats from more powerful others, to silence someone else, or even, to give someone a voice. The use of double-voicing is closely implicated with the ways in which power relations are constructed between speakers according to the interplay of social categories such as gender, age, ethnicity, profession and status. A key focus of this book will be upon gender identities and relations, although as author, I will be self-reflexive about the interplay of multiple social categories that construct individual identities, as well as of the context-bound nature of all social interactions (Butler 1990).

The purpose of this book is to develop a better understanding of the significance of double-voicing within routine linguistic practices, which could be of broad interest to anyone who is interested in the way language works, as well as to scholars of Applied Linguistics and Sociolinguistics. Double-voicing is a micro-linguistic set of practices that is mostly used unknowingly in interpersonal, public and institutional discourse yet can produce profound effects on people’s interactions and relationships. Despite its significance, double-voicing has not been fully appreciated as a wider sociolinguistic phenomenon, an issue which this book seeks to address. Double-voicing is both a unique linguistic construct and a valuable interpretative tool for scholars and practitioners to comprehend the ways in which speakers routinely engage with each other in many every day contexts. The book also aims to be of specific interest to scholars of Language and Gender, in that it explores the discursive interaction between power, gender and linguistic expertise in positioning speakers within a range of institutional settings.

What is double-voicing?

To answer this question, we first need to know what single-voicing is. Bakhtin (1984) described ‘single-voiced discourse’ as having a direct relationship between language and the objects, people and events in the world to which it refers. Its function is primarily to name, inform, express and represent the referential objects of speech. In using single-voicing, the orientation of the speaker is principally to themselves and to perpetuating their own agenda, rather than to engaging with the interests and concerns of others. As this type of direct, unmediated, ‘fully signifying’ discourse is directed towards its referential object, it constitutes, in Bakhtin’s view, ‘the ultimate semantic authority within the limits of a given context’ (1984: 189). In contrast, double-voiced discourse ‘is directed both towards the referential object of speech as in ordinary discourse, and toward another’s discourse, towards someone else’s speech’ (Bakhtin 1994: 105). Whereas a speaker may utilise single-voicing to express one, unmediated utterance, they make use of double-voicing to bring together two (or more) independent utterances to serve their own purposes: ‘in one discourse, two semantic intentions appear, two voices’ (Bakhtin 1984: 189). I explore Bakhtin’s concepts of single and double-voiced discourse in detail in Chapter 2. When referencing Bakhtin’s work, I shall use his given terms of single-voiced discourse (SvD) and double-voiced discourse (DvD; my own abbreviations), but when referencing these concepts in my own work and beyond, I shall adopt the more simplified terms of ‘single-voicing’ and ‘double-voicing’.

The concept of double-voicing largely applies to spoken interactions on an interpersonal level, which will be the primary focus of this book. However, as I review in Chapter 2, double-voicing works on micro- and macro-levels of interaction within different modes and media. Double-voicing is not necessarily easy to identify in everyday language in the same way as the grammatical components of a sentence, such as a verb, noun, adverb or clause, can be. It is highly context-bound, mainly recognisable in contextual use, and thus, localised, ethnographic knowledge is often necessary. However, there are a range of linguistic features/resources that might commonly index (see p. 12) double-voicing such as the use of politeness, hedging strategies, humour, framing, meta-comment, qualification, impersonation of other voices and so on. Double-voicing might also be signified by paralanguage through the use of such features as intonation, pitch, volume, hesitation and pausing. In some contexts, double-voicing may appear similar to ‘being polite’, although double-voicing is not synonymous with politeness, which is just one of its many forms of linguistic expression. Double-voicing features may also appear similar to linguistic humour, or the linguistic enactment of authority. None of these practices are double-voicing per se, but they may be used as linguistic resources by a speaker in order to double-voice, or index double-voicing. It would be challenging, in my view, to establish objective criteria by which to identify the linguistic forms of double-voicing, although I am willing to be proved wrong on this! Consequently, it would be difficult to tag transcripts for double-voicing within large corpora without a complementary qualitative analysis and/or detailed knowledge of the local context, speakers involved and so on. I explain how these categories emerged inductively through the process of conducting a research study in Chapter 4. Furthermore, definitions of double-voicing explored in this book are subject to the limitation that the research I have conducted thus far concerns the English language only and is confined to western European contexts. Double-voicing may well be both language-specific and culture-specific. Until further research is carried out within diverse linguistic and cultural contexts, I make no claims about double-voicing as a universal or cross-cultural phenomenon.

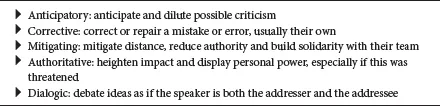

Just as the forms of double-voicing are difficult to identify, complex and interrelated, so are its functions, as this book will endeavour to show. I have explored the different functions of double-voicing in previous research (Baxter 2010, 2011), during which I initially identified four principal types: anticipatory, corrective, mitigating and authoritative. In ongoing research on this topic, I have since added a fifth type: dialogic double-voicing. All types are bound by the common feature that the speaker fears that the interlocutor represents a threat (regardless of whether or not this is true), and therefore adopts different types of reaction to ward off that threat.

TABLE 1.1 The five types of double-voicing

Of the five types, the first and by far the most common type is anticipatory double-voicing, which is where an utterance appears to predict or anticipate the thoughts of the interlocutor and adjusts itself in advance. The anticipatory type may be used when a speaker wishes to deflect perceived criticism of their abilities or actions, for example, when a speaker in a meeting says ‘I have probably got the wrong end of the stick but ... ’ or ‘I realise I am no expert like the rest of you here but ... ’, or ‘I’m sure you think I’m being a complete pain about this ... ’. If used repeatedly, this type of double-voicing can make the speaker appear tentative or defensive as it is often linguistically marked by the use of apologies, qualification, hedging and self-deprecating humour. Anticipatory double-voicing can also take the more assertive form of a ‘pre-emptive strike’: anticipating a criticism from another speaker, and ‘striking back’ before the interlocutor has a chance. Arguably, the four following types are also anticipatory in genre, but the anticipatory type ‘shouts’ that it is so in the various forms in which it is linguistically constructed.

The second type is corrective double-voicing where the speaker attempts to correct or repair an error, often their own. An example of this might be where a manager in the workplace apologises for unfair behaviour to their team by saying, ‘Sorry I lost my temper but I wanted you to see that ... . ’ This is similar to anticipatory double-voicing in that a speaker recognises that others might criticise them if they do not correct the error, so they self-repair in order to limit the damage to the relationship. Corrective double-voicing is linguistically marked by such strategies as apology, seeking agreement with interlocutors, meta-pragmatic comment and ‘role-breaking’ (stepping out of the interactional frame in order to comment on it).

The third type is mitigating double-voicing where speakers aim to reduce the social distance between themselves and their addressees in order to achieve more effective relationships while serving their own agenda. For example, once again from the workplace context, a manager might have pitched an unpopular proposal to their team and followed this up with the double-voiced comment, ‘Look, does anyone want to respond to that? I don’t want you to feel unhappy with this proposal. ’ Mitigating double-voicing overlaps with anticipatory discourse, but primarily seeks to connect with others on an affective or relational level. It is marked by the use of personal pronouns, inviting responses, hedging and qualification, self-deprecating comments, meta-pragmatic comment, and other aspects of relational, polite or small talk (Holmes and Stubbe 2003).

The fourth type is authoritative double-voicing, which is used to heighten impact and display personal power, especially if a speaker feels threatened. So, for example, in delivering bad news, a manager might say to their team, ‘I realise it is tough that you will all lose your bonuses this quarter, but you will just have to learn from this experience. ’ Authoritative double-voicing can be tricky to identify linguistically, and often depends on tone, but is marked by linguistic expressions of authority (Fairclough 1989) such as the use of meta-pragmatic or qualifying clauses (‘I realise it is tough ... ’), followed by a directive, or a deontic modal phrase (‘you’ll just have to ... ’).

Finally, dialogic double-voicing is where the speaker debates ideas with themselves as if they are both the speaker and the addressee. This type either explicitly assumes an overhearing but non-speaking addressee, or can provide an opening for other speakers to join the self-debate (Bell 1984). Dialogic double-voicing is used extensively by academics, for example, in the course of a lecture or in academic writing (e.g. Baynham 1999). This is not simply the act of debating two sides of an argument but rather the act of defending oneself against the anticipated criticisms of the audience, whether students, colleagues or journal reviewers. The perceived voice of the audience/reviewer is always ‘in the head of’ the speaker/writer and hence, the produced spoken or written discourse is reflexively double-voiced in response. An explicit example of this might be where an academic writer was to say, ‘These claims have been extensively debated in research literature, but while they have considerable merit in our view, they do not go far enough. ’ Dialogic double-voicing is marked by such linguistic strategies as comparison and contrast, meta-pragmatic comment, framing, qualification and referencing other authorities.

In order to illustrate the different types of double-voicing and how they interweave, I shall now provide examples of authentic double-voicing in everyday action. The examples in this chapter are from email messaging, a global medium of communication well known for bridging the conventions of both spoken and written discourse (e.g. Crystal 2003). I shall use extracts from emails I have received during my work as a university professor, which reveal some of the ways in which double-voicing is routinely enacted. These emails are exchanged within an institutional frame (Goffman 1974) of working relations between individuals of varying status and levels of authority (student to staff; senior to junior staff and so on). Double-voicing is one of the means by which (often unequal) academic relationships are routinely negotiated and sustained.

Student to staff emails

Students often make requests or ask favours of their university tutors by email with varying degrees of tact and diplomacy. At my own university, students are expected to follow a code of conduct in relation to the ways in wh...