eBook - ePub

Daughter of the Boycott

Carrying On a Montgomery Family's Civil Rights Legacy

- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

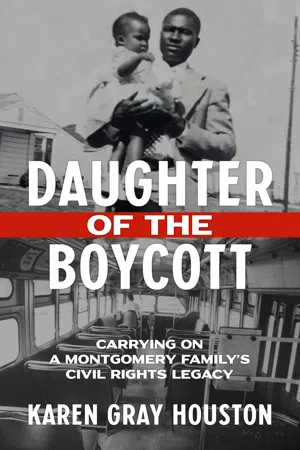

In 1950, before Montgomery, Alabama, knew Martin Luther King Jr., before Rosa Parks refused to surrender her seat to a white passenger, before the city's famous bus boycott, a Negro man named Hilliard Brooks was shot and killed by a white police officer in a confrontation after he tried to board a city bus. Thomas Gray, who had played football with Hilliard when they were kids, was outraged by the unjustifiable shooting. Gray protested, eventually staging a major downtown march to register voters, and standing up to police brutality.

Five years later, he led another protest, this time against unjust treatment on the city's segregated buses. On the front lines of what became the Montgomery

bus boycott, Gray withstood threats and bombings alongside his brother, Fred D. Gray, the young lawyer who represented Martin Luther King Jr., Rosa Parks, and the rarely mentioned Claudette Colvin, a plaintiff in the case that forced Alabama to desegregate its buses.

An incredible story of family in the pivotal years of the civil rights movement, Daughter of the Boycott is the reflection of Thomas Gray's daughter, award-winning

broadcast journalist Karen Gray Houston, on how her father's and uncle's selfless actions changed the nation's racial climate and opened doors for her and countless other African Americans.

Five years later, he led another protest, this time against unjust treatment on the city's segregated buses. On the front lines of what became the Montgomery

bus boycott, Gray withstood threats and bombings alongside his brother, Fred D. Gray, the young lawyer who represented Martin Luther King Jr., Rosa Parks, and the rarely mentioned Claudette Colvin, a plaintiff in the case that forced Alabama to desegregate its buses.

An incredible story of family in the pivotal years of the civil rights movement, Daughter of the Boycott is the reflection of Thomas Gray's daughter, award-winning

broadcast journalist Karen Gray Houston, on how her father's and uncle's selfless actions changed the nation's racial climate and opened doors for her and countless other African Americans.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

HILLIARD BROOKS

FIVE MONTHS BEFORE I WAS BORN, my father, Thomas Gray, was plotting to take on the white establishment in Montgomery, Alabama, to protest the shooting of a black man by a white police officer. It must have been a scary time for my mother. She and Dad had barely been married a year and were just starting their new family.

“Hilliard Brooks may have been drunk and disorderly, but that was no reason to kill him!” my father exclaimed—to his business partner, to his other friends, to the veterans he taught math to in night school, to my mother, to anybody who would listen. He was furious.

It was August 1950, long before many people had ever heard of Rosa Parks. Martin Luther King Jr. was attending seminary school in Pennsylvania. It was five years before Dad drove his car every day to pick up passengers during the bus boycott.

Society was segregated. Separation of the races on city buses was just one way to keep black people in their place. My father’s youngest brother, Fred, was finishing his undergraduate studies at Alabama State College. Dad had just teamed up with a former high school and college classmate, William Singleton, to own and operate Dozier’s Radio, TV and Appliances Sales and Service.

Then came the news. Their buddy Hilliard Brooks had been killed. The headlines screamed out from the pages of the Montgomery Advertiser, the city’s daily newspaper: GUNSHOT WOUND FATAL TO NEGRO; 3 WOUNDED AS POLICEMAN FIRES AT NEGRO.

When Thomas Gray read that a fellow veteran and former neighborhood football pal had been fatally shot by a white police officer, he flew into a rage, not afraid of confrontation. It was time for action. He showed the article to his friend Ronald Young, insisting, “We can’t let those jokers get away with that.”

The incident occurred August 12, 1950. Nobody doubted that Hilliard Brooks was inebriated. Witnesses agree he was unruly when he tried to board a bus on Dexter Avenue, the main street in downtown Montgomery. But there are several versions of what happened next. One was that Brooks was shot when he got off the bus after exchanging words with the white driver for refusing to pay his dime bus fare. Another has it that Brooks had been drinking and dropped his money on the floor. When the bus driver told him to pick it up, Brooks said, “You pick it up.”

Whatever happened, the bus driver summoned a nearby police officer to deal with a “disturbing the peace” complaint. Brooks must have gotten off the bus. As historian J. Mills Thornton tells the story in his book Dividing Lines, “Police Officer M.E. Mills pushed Brooks to the sidewalk and shot him to death after he struggled back to his feet.” According to at least one account, Brooks was coming toward the officer, but other witnesses reported that Brooks was standing with his arms at his side.

An article in the newspaper the day after the shooting said Brooks was drunk and cursing. The Advertiser said there were hundreds of witnesses, and some of them called the shooting “reckless and needless.” The newspaper quotes a detective as saying the bullet went through Brooks’s stomach and injured two bystanders. A man and a woman were struck in the leg. According to the Advertiser, Officer M. E. Mills said Brooks hit at him and pulled the whistle and chain from his shirt. The officer pushed Brooks away. That’s when he fell, got up, and allegedly advanced toward the policeman. The officer shot him. Brooks later died in the hospital.

Not a big man, Brooks weighed about 145 pounds. One female witness was quoted as saying, “The boy appeared to be so intoxicated that he could have been subdued easily. I do not think the policeman shot in self-defense. I think he took the law into his own hands.”

It was the beginning of one of many sagas predating the 1955 bus boycott that my father recounted to me, late in his life.

In August 1950 my father was twenty-six, about the same age and, at five foot eight and around 160 pounds, not that much bigger than Brooks. Dad wore his dense black hair closely cropped, sharply parted on the right side. His mustache was always neatly trimmed, with a few hairs that always seemed to curl down around both sides of his lips, dressing up his smile.

He was teaching math and civics classes at St. Jude Educational Institute. St. Jude was a new private Catholic elementary-through-high-school for Negroes on a campus of beautiful redbrick buildings that included a church and Montgomery’s first hospital for African Americans. The sprawling fifty-six-acre site, founded by a Catholic priest who wanted to improve the plight of the downtrodden, was called the City of St. Jude. The Catholics named it after Saint Jude Thaddeus, one of the twelve apostles of Christ, the patron saint of difficult and impossible causes.

When my mother, Juanita, was working there, she taught English. Both she and my father were recent graduates of Alabama State College for Negroes (today Alabama State University). Both were helping vets who were trying to complete their high school equivalency work under the auspices of American Veterans Inc. (AMVETS), which has a long history of sponsoring programs to assist veterans in specialized training. Hilliard Brooks also belonged to that AMVETS post. Ronald Young, a neighbor and friend of my father, was the post commander.

The day the article about Hilliard was published in the Advertiser, Dad took the paper with him to St. Jude. The news was all the buzz in the hallways as teachers and students headed to class that evening. Many of them knew Hilliard.

“Do you believe this?” my father said, holding the paper above his head and shaking it in the air. “I used to play sandlot football with Hilliard when we were kids.”

On his way to teach his math class, Dad bumped into his AMVETS commander. “Look,” Dad told Young, “these guys think they can get away with murder.” They both decided something had to be done. Young lived a few blocks from our house, and Dad told him to stop by after classes were over that evening so they could talk.

My parents purchased their first home not long after they married in August 1949. The house was in the Mobile Heights section of the city. Mobile Heights was designed for Negro veterans returning home after serving in World War II and later the Korean War. As Montgomery expanded, it became an ideal location for vets to use the GI Bill to buy a new house. A tract house development, it was the first of its kind in the city—suburban living for many people of color who had previously lived in low-income neighborhoods in the inner city and for some who had moved in from rural areas and farms.

LEFT: Willie Lee Dyer Martin Emanuel, my grandmother, visiting our family home in Montgomery on the birth of her youngest daughter’s second child, Thomas Gray Jr., in June 1952. RIGHT: Fred D. Gray, my uncle, was a frequent visitor to our home in Mobile Heights and sometimes babysat me and my brothers.

There were 511 homes in Mobile Heights. They were two- and three-bedroom ranch houses made of stucco, in white and pastels. Some of the homes were brick. Some had car ports. Predictably, the cookie-cutter design was a single floor with low-pitched roofs and shuttered windows. Our house was on Mobile Drive at the corner of Tuskegee Circle, and it still stands. I drive by to see it whenever I’m in Montgomery. There are sidewalks there now. In front of our tiny stucco home, someone carved OBAMA on the concrete while it was still wet.

Mom was popular, pretty, and a petite five foot three. She and my father met and courted in college. Fair-skinned, with a coquettish twinkle in her eye, she had a way of walking that made people take notice. When my two brothers and I were older, we called her “swivel-hips.” I was slightly taken aback one day as a teenager when she told me I should put a little more “bounce” in my walk.

The way the story goes, my mother, attractive and sassy, was sashaying down a street on campus one day, right past my dad and some of his friends, who were just hanging out. He whistled. She turned around, and the rest, as they say, is history. Dad helped Mom with her math homework and taught her to play chess. He was a real catch. He played football and was also president of his campus chapter of the Omega Psi Phi fraternity.

After graduation, they married in a small ceremony with just a couple of witnesses at St. John the Baptist Catholic Church.

“Gray, I know you and your family like attending church at Holt Street Church of Christ, but you know I like the organ music at St. John’s. It’s a beautiful church, and I would love it if we could have our special ceremony there,” she cooed. If Dad thought it would upset his mother that no family would be in attendance, he didn’t say; he just went along with the program.

That tells you something about Juanita. She married a man who, like most of the males of his generation, played the dominant role in their relationship. Dad’s church was very important to him. But on one of the most important days of his life, he succumbed to the wishes of my mother: they would tie the knot in her church. Juanita might have appeared submissive, but when she wanted something, she had a way of getting it. She made her point that day, but to keep the peace, for the rest of her life, she attended my father’s church.

LEFT: Juanita Emanuel as a student at Alabama State College for Negroes around 1948, when she and Thomas Gray were courting. RIGHT: Thomas Gray sporting one of the apple caps he was known for wearing in college.

On a very cold day in January 1951, I was born at Hale Infirmary, 325 Lake Street in the middle of town. It was the closest thing black people had to a hospital in the city then. It was for Negro patients, staffed by caring Negro physicians and Negro nurses. Hale was a gift. At the time, Negroes were either denied admission to white hospitals or accommodated in segregated, subpar units, sometimes in basements or attics.

From the outside, the infirmary had none of the appearance of modern-day hospitals. It was an old two-story white wood-frame building with steeples. It looked more like an old antebellum mansion in need of a touch of paint and a tad more maintenance. My mother and another young woman, who was to become a local civil rights notable, Johnnie Carr, were both patients at Hale that week having babies. Mom and I went home to our new house in Mobile Heights.

“You been in touch with Bruh Nixon?” Young asked Dad the evening he stopped by to talk about the Hilliard Brooks situation.

“You know I have,” my father replied, smiling an impish grin.

E. D. Nixon (Edgar Daniel Nixon) was affectionately and respectfully known as “Brother Nixon,” or in the vernacular of the time, “Bruh.” Before he died in 1987, he was the go-to guy in Montgomery for all things civil rights. Nixon was a Pullman porter who worked trains from Montgomery to Chicago. He was heavily influenced by A. Philip Randolph, who organized Negro sleeping car porters into the nation’s first black union. Randolph inspired Nixon to become leader of a branch of the union in Montgomery. According to historians, Nixon was impressed with Randolph’s special brand of civil rights activism. He used collective bargaining and nonviolent direct action to get better benefits and treatment for black workers, who were overworked and underpaid.

Nixon was a bundle of contradictions. He was a big, tall, dark-skinned man with a booming voice and more connections than just about any other black man living in Montgomery. But he was an uneducated man who often misconjugated his verbs when he spoke. His lack of education and fractured speech may have cost him the recognition and honor he felt he deserved later for the large role he played in the success of the bus boycott.

In the 1940s and ’50s, Nixon selflessly struggled to fight racial discrimination and increase black voter registration. He was Mr. It in Montgomery. Nixon knew people—white people—such as judges and lawyers and police officers and newspaper reporters. If you had a complaint that needed resolving, you went to him for assistance. Dad had a lot of respect for E.D.

I remember when we were old enough to go for Sunday drives, Dad would take the family to Nixon’s house on Cl...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication Page

- Contents

- Foreword by Fred D. Gray

- Preface

- Introduction

- 1. Hilliard Brooks

- 2. Road Trip

- 3. Veterans Protest

- 4. Uncle Teddy: To Destroy Everything Segregated

- 5. The Brothers Gray: The Early Years

- 6. Rediscovering Montgomery

- 7. Lunch with Rosa

- 8. Who Was Rosa, Really?

- 9. The KKK Chapter

- 10. Claudette Colvin, Teenage Pioneer

- 11. Boycott: Day One

- 12. Ray Whatley

- 13. King Parsonage Bombing

- 14. The Arrests

- 15. White Allies

- 16. Radio Days

- 17. The Movement Wedding

- 18. MLK and the Barber

- 19. The Police Chief’s Daughter

- 20. The Bus Manager and His Family

- 21. Ann Carmichael

- 22. The Help

- 23. World War II

- 24. Displaced Refugees

- 25. Cleveland

- 26. Justice Delayed

- 27. The Wake

- 28. Lasting Legacy

- Acknowledgments

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Daughter of the Boycott by Karen Gray Houston in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Social Science Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.