eBook - ePub

Understanding Child Sexual Abuse

Perspectives from the Caribbean

A. Jones, A. Jones

This is a test

Share book

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Understanding Child Sexual Abuse

Perspectives from the Caribbean

A. Jones, A. Jones

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This book is the first comprehensive study of child sexual abuse in the Caribbean, exploring issues such as the ontology of childhood, links between slavery, colonialism and present-day gender-based violence, the impact of child sexual abuse on the brain and child protection after natural disasters.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Understanding Child Sexual Abuse an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Understanding Child Sexual Abuse by A. Jones, A. Jones in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Social Work. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Context, Theory and Caribbean Realities in Tackling Child Sexual Abuse

1

The Nature of Paradise

Introduction

In the popular imagination, the Caribbean is often typified by striking images of sunny days at the beach, fresh coconuts, colourful road-side fruit stalls encompassing all the wonders of the tropics, the warmth of the islands’ peoples; all cast alongside the pristine, sparkling waters of the Caribbean Sea. This is indeed an accurate snapshot of Caribbean life, if in part. This is what sells the Caribbean; that it is a haven away from bitterly cold winters and smart-phone agendas. This chapter does not seek to detract from the vivid imagery, the tourism-driven advertisements of the Caribbean, since this is part of our way of life and neither does it aim to de-construct those ideas associated with Caribbeanness. Rather, the main aim of this chapter is to build other dimensions onto that of the ‘paradisiacal’ Caribbean in an attempt to introduce the reader to the multiple historical, social, political and economic layers that lie beneath its idealistic surface. This contextualisation is important in understanding child sexual abuse (CSA), the focus of this book, since issues of domination and subjugation that underpin childhood victimisation do not emerge in a vacuum and are located within particular socio-historic specificities. The activities of international development agencies, and the research and policy developments crafted in their wake, have tended to subsume the Caribbean as a territory within the category ‘Latin America and the Caribbean’. While the reasons for this may be wholly pragmatic, this has contributed to several misconceptions, first, that there are more similarities than differences among the Caribbean and Latin America and, secondly, that the Caribbean is homogenous. This has also meant too often, that in research concerning children, Latin America is held as speaking for the Caribbean (excepting for those countries that receive specific focus because of their extreme challenges such as Haiti). Within the Caribbean, the most wide-ranging research on child sexual abuse to have been conducted to date (Jones and Trotman Jemmott, 2009), does indeed make the point that of the six countries studied, which collectively were said to be representative of the region, similarities far outweighed differences and the argument for harmonised regional approaches that share expertise and resources was made. Nevertheless, there is a case for localised responses that can address differential nuances in manifestations of abuse when needed and it is important, therefore, to understand the Caribbean both as a whole and also, as a sum of its individual parts. The chapter starts by exploring some of the economic, socio-demographic and cultural similarities and differences that exist within the Caribbean – to re-examine the notions of oneness and perceptions of homogeneity. It goes on to explore some of the challenges the Caribbean has faced in recent history to give, first, an appreciation of the other side of paradise and, secondly, to provide comment upon the historical context from which the contemporary Caribbean emerged. Finally, this chapter discusses some of the present-day characteristics and challenges of the Caribbean.

Defining and describing the Caribbean

The Caribbean is comprised of its archipelago, from Trinidad and Tobago at the southernmost tip, to Jamaica in the north and the Bahamas. Many of these countries are politically independent, but the Caribbean is also home to the Dutch, inclusive of the Netherlands Antilles; French, inclusive of Guadeloupe, Martinique, St Barthélemy and St Martin; British, inclusive of Anguilla, British Virgin Islands, Cayman Islands, Montserrat and Turks and Caicos Islands; and United States (or American) West Indies, inclusive of Puerto Rico and United States Virgin Islands; and many other small island states. As part of the British Commonwealth, Belize and Guyana are also included as Caribbean, by some definitions, although they are geographically parts of Central and South America respectively. The collective history of Belize and Guyana as members of the British Commonwealth and the British West Indies supersedes their geographic locations and demonstrates that the Caribbean is more than just an island chain.

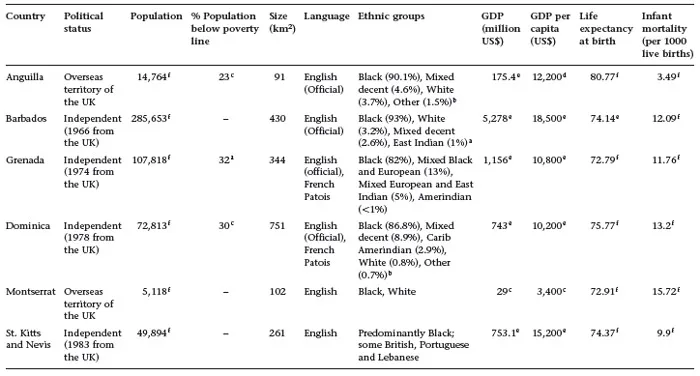

It is not within the scope of this chapter to discuss each Caribbean country, although the essence of the entire Caribbean will be touched on, and some specific country examples extrapolated. This chapter introduces the six participating countries in Child Sexual Abuse in the Eastern Caribbean (Jones and Jemmott, 2009), which are Anguilla, Barbados, Grenada, Dominica, Montserrat and St Kitts and Nevis. Table 1.1 (see overleaf) lists these six countries focusing on some key socio-demographic, political and economic indicators, to provide a context for the Jones and Trotman Jemmott study. In exploring CSA within and across six countries, Jones and Trotman Jemmott (2009) found differences among the countries, for example, on the concepts of childhood, pregnancy and motherhood; and also some similarities, like the taboos associated with and silencing of CSA. Such disparate or similar findings should be viewed as complementary to the indicators shown in Table 1.1, as the six countries are neither homogenous nor isolated from one another.

Table 1.1 Key indicators for six Caribbean countries

Notes:

a2000, b2001, c2002, d2008, e2009, f2010.

Source: Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) (2010).

As Table 1.1 indicates, the six Caribbean countries vary by size, political status, income and culture. There are also some striking similarities. Perhaps the single most binding force within the Caribbean is the history of colonisation; this has left many countries with similar languages (predominantly English and French Patois), the creation of a Creole culture (although this can vary from country to country) and for those countries who are politically independent, the trials of young democracies.

As this section and Table 1.1 illustrates, it is difficult to imagine the Caribbean as a whole, without giving consideration to each of its parts. There have been many attempts at creating a unified Caribbean, although this thrust has come mainly from countries belonging to the British Commonwealth. In brief, the West Indies Federation was created in 1958 and dissolved in 1962; its aim was to prepare the member states (10 British Colonies: Antigua and Barbuda, Barbados, Dominica, Grenada, Jamaica, Montserrat, the former St Kitts-Nevis-Anguilla, St. Lucia, St. Vincent and Trinidad and Tobago) for independence and create a political union (Caribbean Community [CARICOM], 2009a). It is noteworthy that the University College of the West Indies (UCWI), which had opened in 1948 in Mona, Jamaica extended to another campus at St Augustine, Trinidad in 1960 while the Federation was still afloat (CARICOM, 2009a). Following the dissolution of the Federation, CARICOM was formed in 1973, with its predecessor being the Caribbean Free Trade Association (CARIFTA) from 1965 to 1973, whose member states included Antigua and Barbuda, Barbados, Belize, Dominica, Grenada, Guyana, Jamaica, Montserrat, St Lucia, the former St Kitts-Nevis-Anguilla, St Vincent and the Grenadines and Trinidad and Tobago. The formation of CARICOM in 1973 superseded CARIFTA, whose main aim was economic unification of member states (CARICOM, 2009b). CARICOM’s objectives were more broad-based and in addition to economic integration aimed to improve the living standards of member states, increase economic productivity, development and convergence, and expand trade with non-member states (CARICOM, 2009c). CARICOM has since adopted further protocols to create a single market and economy, with the CARICOM Single Market and Economy (CSME) being established as of 2006. Attempts at regional integration have at best been rocky. Differences in national income, vulnerability, political status and intra-regional political squabbling led to Payne and Sutton’s (2001, p.200) assertion that ‘the answer to the question of whether CARICOM has been a success or a failure is manifestly that it has been both’. The ideological significance of CARICOM is that it has survived, albeit with periods of tension, suggesting that the member states recognise the benefits of unity, economically, socially, internationally and otherwise.

Complicating the matter of defining the Caribbean, the region has been characterised by migration. Smith et al. (2004) explain that in many instances single parents migrate to a host country, followed by children. Host countries are most commonly the US, Canada and the UK (Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean [ECLAC], 2006) although it is not uncommon for inter-island migration to occur in much the same manner, with remittances being sent for dependents in the home country. Transnational migration has also eroded the concept of a unified Caribbean with increased transnational trade, within and outside the Caribbean (Robotham, 1998). That the CSME encourages the free movement of professional and skilled peoples across member states also destabilises the concept of a discrete Caribbean. ECLAC suggests that about 3 per cent of the Caribbean population be considered migrants, within the region itself (ECLAC, 2006). ECLAC (2006) also indicates that people of Caribbean origin make up approximately 10 per cent of all foreign nationals living in the US; a considerable statistic given the relative small size of the Caribbean.

It is perhaps surprising that scholarship and sport have made significant inroads in promoting a Caribbean identity, a de facto objective of sorts. It seems that the University of the West Indies (UWI) and West Indian cricket have been able to bring forth the spirit of togetherness, of oneness and of a unified Caribbean identity. The West Indian Federation could not have foreseen that the University College of the West Indies, later the UWI, would be such a uniting force of Caribbean people as exemplified by the growth of the UWI as an academic institution serving the Caribbean. The Chancellor of the UWI, Sir George Alleyne states,

We all know of the failure of the West Indian Federation and history records the survival of the university through that difficult period. What is not so clearly articulated is the repair of the damaged DNA, its role in creating the phoenix of a different Caribbean arrangement that is now attempting to spread its wings (Alleyne, 2008, paragraph 6).

The UWI now has four main campuses in Mona, Jamaica; St Augustine, Trinidad; Cave Hill, Barbados and the Open Campus, which serves a further twelve Caribbean countries.

Writing in an undoubtedly more glorious era of West Indies cricket than the present day, Manning (1981) speaks of the symbolism of cricket, of African-Caribbean peoples donning ‘cricket whites’ to play what was typically the coloniser’s game. Putting aside the Caribbean tendency to impose a socio-historical, particularly colonial, stamp on Caribbean issues, West Indies cricket has served the Caribbean well in promoting unity and a Caribbean identity, with a vigour and passion that nothing else has been able to match as described by Lakhan (2005),

There is nothing more West Indian than cricket. There may be things that are more Trinidadian or Guyanese, or things that come more readily to mind when one thinks of Jamaica or Antigua – idiosyncrasies of each country in the chain – but no institution of government, trade, or culture has been more enduring. Indeed, it might be more accurate to consider it not the most West Indian thing, but the only true West Indian thing; the only thing that belongs equally to all the countries that comprise the West Indies (Lakhan, 2005, paragraph 1).

This was exemplified in no better way than when West Indian cricketer Brian Lara broke the world test run record in Antigua in 2004, a record he previously broke in 1994 (perhaps coincidently against England on both occasions; for Caribbean spectators adding further fodder to the inherited memories of the coloniser/colonised relationship). Lakhan (2005, paragraph 2) aptly describes the nuanced power differentials of the coloniser and colonised by suggesting, ‘Together, these countries built a team that could challenge their erstwhile colonial masters ‘in the pre-independence era and thereafter. Spencer (2008, paragraph 7) explains that the leaders of the Caribbean in the mid-1960s sought ‘West Indian unity beyond the boundaries of cricket’, so important was the game in the consciousness of Caribbean people that it could be identified as a unifying factor beyond even formal economic and political agreements.

Imagining a de-constructed Caribbean may prove more valuable in trying to explain the region. Depending on the stance, the Caribbean can be re-constructed geographically, for example, Lesser Antilles, Greater Antilles, Windward Islands, Leeward Islands; politically, independent territory, overseas territory, department or collectivity; historically, members of the British commonwealth; economically, Less Developed Countries (LDCs) and More Developed Countries (MDCs) or in whichever classification so suits the point of discourse. The ideology of Caribbean oneness can lead to an oversimplification of the specific countries that make up the Caribbean. It is important that each country be allowed to demonstrate its will and spirit, its own heritage and journeys into the twenty-first century. The Caribbean and its people may best be viewed with fluidity; literally with peoples defying conventional state boundaries and metaphorically, peoples who are organic, who adapt to their changing environments and make out of whatever circumstances they face or have faced, something that is uniquely Caribbean.

Challenges in recent Caribbean history

It is well known that the Caribbean was a centre of slavery during colonisation by various European nations. The English-speaking Caribbean, though changing hands from country to country, was largely influenced by English domination. Post re-discovery, the plantation system dominated the economic landscape of these islands, whose goods and profits served the growth of the British motherland (see Best, 1968, for detailed discussion of the plantation system). This was perhaps the beginning of dependence, if maladaptive, on foreign intervention of extraneous power-holding over the Caribbean nations’ economies. The eventual retreat and forced obscurity of indigenous peoples, namely Caribs, from Dominica’s trading system is testament to the ultimate power which the European colonisers held in the mid-1700s (Honychurch, 1997). Slavery and its plantation system had only one aim, to profit the motherland; anything detracting from this mission was not to be in the equation.

Eltis and Engerman (2000, p.129) note the influence of the Atlantic sugar plantation system, ‘its direct contribution to the economic growth of any (European) nation was trivial’, in the late eighteenth century. However, the production of sugar, along with other goods such as textiles, iron and coal did in fact contribute significantly to English economic growth (Eltis and Engerman, 2000). That sugar was believed to be the mainstay of the English economy is probably related to its symbolic relevance to the plantation and that vicious form of labour, slavery. Regardless of how miniscule the economic contribution of sugar was, it remains in the ...