eBook - ePub

Economic Policies, Governance and the New Economics

P. Arestis, Kenneth A. Loparo, P. Arestis, Malcolm Sawyer

This is a test

Share book

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Economic Policies, Governance and the New Economics

P. Arestis, Kenneth A. Loparo, P. Arestis, Malcolm Sawyer

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This volume concentrates on international issues that relate to economic policies and governance. It is essential reading for all postgraduates and scholars looking for expert discussion and debate of the issues surrounding the case for new economic policies at the global level.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Economic Policies, Governance and the New Economics an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Economic Policies, Governance and the New Economics by P. Arestis, Kenneth A. Loparo, P. Arestis, Malcolm Sawyer in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economics & Econometrics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Great Recession, Capital Market Failure and International Financial Regulation

1.1 Introduction1

For at least a decade before the onset of the ‘great recession’ in 2007 it had been clear that systemic global capital market failure is a far more significant driver of the crisis than government monetary or fiscal policy. Some initial steps have been taken towards re-regulating national financial markets to increase stability and reduce uncertainty; but at the international level there is little progress despite initial commitments by the governments responsible for the greater part of the world economy (G20, 2009).

Although there is clear historical evidence that financial crises are closely linked to capital mobility (Reinhart and Rogoff, 2009), G20 policy statements do not address this as a multilateral issue. None the less, in effect almost all governments and central banks have acted so as to reduce mobility by protecting national banking systems while increasing risk aversion among financial intermediaries has led to increased home bias among investors.

If there is a parallel with the Great Depression of the 1930s, it is not to be found in the restrictions on imports because global trade liberalization and the construction of the World Trade Organization (WTO) at the end of the twentieth century have largely eliminated the power of governments to raise tariffs or apply import quotas. Competitive devaluation between economic powers is unviable in a world of flexible exchange rates where major nominal parities are no longer set administratively, although excessively low (or even negative) real interest rates have the effect of avoiding – or rather attempting to avoid – currency overvaluation; they are weak instruments at best. Rather the parallel is to be found in attempts of national regulators to protect their domestic banking systems through prudential regulation (IMF, 2012a). This in turn has reduced the negative impact of capital flows: not through capital controls as such but rather through the socialization of national balance sheets – the accumulation of foreign exchange reserves and bank bailouts.

Cross-border capital flows have grown enormously over the past three decades and have become more volatile and riskier rather than stabilizing in a mature market as standard theory would predict (Milesi-Ferretti et al., 2011). Surges of capital occur sequentially, and are persistent. Further, both surges and sudden stops are becoming increasingly globally synchronized. A number of factors contribute to these trends, including structural changes, the rapid expansion of financial markets, the rise of large cross-border institutions, and the acceleration of financial interconnections among countries. While the crisis showed that both advanced economies and emerging market economies (EMEs) could face risks from capital flows, the differing pattern of flows among these two groups determined the types of risks that manifested themselves (IMF, 2011a, b; IMF, 2012c).

Transactions among a small set of large advanced economies account for the majority of flows and stocks of external assets, and embed potentially important risks. While net flows are not so large among advanced economies relative to their GDP as those for developing, the former account for the bulk of gross global capital flows. This trend has been largely driven by the acceleration of portfolio investment flows which have proven to be the most volatile in recent years; the other investment segment mainly reflects banking-related flows, mostly driven by European banks. Additionally, a few advanced economies account for the bulk of global investment outflows and are also home to ‘systemically important financial institutions’ (SIFIs) and global capital markets, which makes them important sources and transmitters of global shocks.

In contrast to the large advanced economies, capital flows to EMEs and small developed economies (notably the European periphery) are larger on a net basis relative to host GDP, directly affecting macroeconomic stability through the funding channel. Not only is macroeconomic stability in these economies vulnerable to even temporary halts in flows, but in recent years the risks have compounded by increased volatility, and, until recently, greater recourse to debt financing in foreign currency. For instance, banks domiciled in advanced countries overwhelmingly participated in foreign currency financing in EMEs, but a much smaller group extended loans in domestic currency.

This paper sets out to explore the implications of these large fluctuations in international capital flows unrelated to the current account financing that had concerned John Maynard Keynes and his colleagues at Bretton Woods seven decades ago. The analytical relationship between global capital market failure and macroeconomic instability is outlined in section 1.2 of this paper, by drawing on concepts of credit market rationing, portfolio home bias, uncovered interest rate parity and the nature of the risk premium. In section 1.3 the very different responses of advanced economies as a group and EMEs to the crisis – reflecting lessons learned from recent past as well as distinct fiscal constraints – are explored in the context of the framework of section 1.2 – where it is shown that the level of national indebtedness has a crucial influence on both output (and employment) and the risk premium and thus the behaviour of capital flows. Both groups have in effect engaged in extensive socialization of macrofinancial fixed assets and liabilities such as external reserves and major bank liabilities (and in the case of housing, assets as well) in addition to the traditional sovereign debt, essentially as a means of national institutional insurance against sudden changes in global risk aversion.

Section 1.4 discusses the treatment of risk aversion in the standard literature in view of its importance in both theory and practice as set out in the previous two sections. A fundamental breach is revealed between mainstream economists’ belief in the stability of the risk aversion parameter (derived from the derivatives of the foundational utility function itself) on the one hand, and financial analysts’ conventional wisdom and measurement of its path-dependent instability on the other. Thus not only is financial socialization in the face of unstable global risk aversion best understood in an explicitly Keynesian framework, but also Keynes’s own brief yet influential references to ‘animal spirits’ can be fruitfully seen as an expression of this concept of risk appetite. For it is the case that not only is financial socialization in the face of unstable global risk aversion best understood in an explicitly Keynesian framework, but also Keynes’ brief yet influential references to ‘animal spirits’ can also be best understood in this context. Section 1.5 concludes with some implications of this argument for future steps in the pressing task of reform of the international financial architecture seventy years after the first attempt.

1.2 Global capital market instability

Financial markets are inherently unstable, because the assets being traded are claims on future income and these in turn depend not only upon unknown future events but also upon market participants’ view of the likelihood of such events. International markets are even more unstable because they lack both the regulatory systems to maintain bank integrity on the one hand, and the macroprudential policy measures to ensure market stability on the other that characterize national systems.

This instability causes crises in ways that other international markets (such as those for commodities) do not, even though they too can exhibit large price fluctuations. This is because financial flows reflect adjustments in stocks – that is, balance sheets. Markets can only truly clear when participants (banks, households, firms and governments) have reached their desired balance sheet positions, and this may take some time. Indeed, because the potential equilibrium foreseen by market participants is itself always shifting, this process can take years to complete – if it occurs at all. The real effects of these adjustments on output, investment, employment and trade can be large and politically difficult to adsorb. Further, balance sheet adjustments by one sector – particularly banks – can have enormous effects on other sectors (households, firms and governments) as leverage changes. Last but not least, market expectations as to the value of particular asset classes, or the future of the world economy or as to the behaviour of other economic (and political) actors – can all shift considerably and rapidly in response to changing risk aversion, itself a response to political and market shocks.

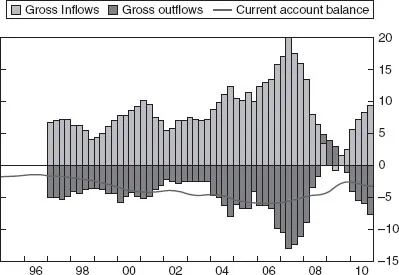

In other words the extent of cross-border financing is not mainly reflected in net capital flows but rather in gross flows and balance sheet positions (Borio and Disyatat, 2001; Milesi-Ferretti et al. and others, 2011). This much is evident from the US balance of payments, as is illustrated by Figure 1.1. The current account imbalance has averaged about 3 per cent of US GDP over the past 15 years, with the band of variation lying between 2 and 5 percentage points; while the exact size of the deficit clearly reflects the long-term demand cycle as would be expected. In the case of the USA (with no significant foreign exchange reserves) the net capital inflows match the current account deficit by construction. In marked contrast, the gross capital flows are not only much larger (outflows averaging 10 per cent and inflows 7 per cent of GDP over the period) but also fluctuate enormously and erratically in the short run and thus clearly respond to factors other than trade and factor payments in the current account. In particular, the ‘great recession’ has seen gross inflows fall from 20 per cent of GDP in mid-2007 to 2 per cent in 2009, and then recover to 10 per cent by the end of 2010; while the figure for net capital flows (the current account balance) has moved steadily from 4, though 3 to 2 per cent of GDP as the economy decelerated.

Figure 1.1 US gross capital flows, 1995–2010

Source: Borio and Disyatat (2011).

Other parts of the world economy with structurally surplus current account positions (traditionally Germany, Japan and OPEC, of course, but more recently also East Asia) exhibit a similar pattern, although in reverse, with gross capital flows behaving quite differently from net flows in terms of both size and fluctuations. Figure 1.2 shows these gross flows as a percentage of GDP in ‘Emerging Asia’, where the compensating items are not only the current account balance but also the change in reserves. Over the period since the ‘Asian Crisis’ reserve accumulation has more or less balanced current account surpluses (a deliberate policy stance), so net capital movements have been effectively near-zero. None the less, gross capital flows have been very large – reaching US$750 billion in 2007 after a five-year build-up during the global boom – only to collapse to pre-boom levels in 2008. Again, as in the case of ...