eBook - ePub

Animation, Embodiment, and Digital Media

Human Experience of Technological Liveliness

K. Chow

This is a test

Share book

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Animation, Embodiment, and Digital Media

Human Experience of Technological Liveliness

K. Chow

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Animation, Embodiment and Digital Media articulates the human experience of technology-mediated animated phenomena in terms of sensory perception, bodily action and imaginative interpretation, suggesting a new theoretical framework with analyses of exemplary user interfaces, video games and interactive artworks.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Animation, Embodiment, and Digital Media an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Animation, Embodiment, and Digital Media by K. Chow in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Informatique & Matériel. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

InformatiqueSubtopic

MatérielPart I

Introduction

Marriage of two slippery terms on a new platform

This book touches upon the concepts behind two perplexing terms, ‘animation’ and ‘embodiment’, and in particular how these concepts have evolved with the latest development of digital media.

The term ‘animation’ has multiple meanings. In daily usage, it refers to a medium, a form of art or entertainment, which involves a sequence of still images or cartoons shown in succession to produce an illusion of movement. Its Latin root animare, however, literally means ‘to fill with breath’ – the act of bringing something to life or the state of being full of life. As the animation theorist Alan Cholodenko puts it, the term is ‘bedeviled’ by two definitions, namely ‘endowing with movement’ and ‘endowing with life’. In the former animation is considered a medium (particularly on film), whereas in the latter it is an idea (Cholodenko, 1991, p. 15). The crux here is whether movement is the sole definitive attribute of life, which is debatable. In other words, is motion itself enough to give the illusion of life? Inanimate objects, such as a vehicle or an electric fan, show movement. Natural phenomena such as lightning or snowfall appear to us as motion. Conversely, life forms like coral and plants might move at such an extremely slow speed that we can barely perceive it with the naked eye.

‘Embodiment’ is another equivocal term that is hard to grasp. In daily usage, it is the physical manifestation of an abstract or intangible idea, thought, or feeling. In the contexts of cognitive science and the philosophy of mind, it specifically refers to the bodily aspect of human cognition. In the latter case, the term has a double sense: ‘the physical structures’ of our body and ‘the lived, experiential structures’ that enable our sensory perception and motor action, which the phenomenologist Maurice Merleau-Ponty sees as the two sides of embodiment, namely the biological and the phenomenological (Varela et al., 1991, pp. xv–xvi). The two sides, rather than in dichotomy, are in reciprocal relation. We cannot sense or act upon the world around us without our bodies; nor can we even know the physical existence of our bodies without the sensorimotor experience of seeing, touching, or internally sensing where our body parts are; that is proprioception in physiology.

Animation and embodiment, two slippery terms, seem to meet and intertwine with each other in the digital age. With the latest advances in computer graphics and interactive multimedia technologies, digital environments including graphical user interfaces, websites, video games, or computer-based artistic works have been imbued with the illusion of life. These digital media artifacts carry visualized information or visible contents that commonly consist of interactive animated elements that bring us wonder via sensorimotor experience. We still remember the amusement when we flicked over a touchscreen, a tablet computer, or a smartphone for the very first time and saw the interface panel sliding accordingly with the inertia effect. We are amazed by interactive installations or projections in museums, galleries, or even shopping arcades that seem to ‘react’ to our body movements. These interactive dynamic experiences are so vivid that we almost mistake them for autonomous beings, oblivious to the computing technology at work. In fact, animation and embodiment go hand in hand to shape our experience. On one hand, we feel that the digital environment is animated. By ‘animated’, I mean the medium is ‘endowed with life’ rather than just ‘movement’. The visible digital objects show various kinds of liveliness in phenomena such as motion, reaction, adaptation, and transformation. On the other hand, through experiencing these phenomena of liveliness we feel that our bodies are in touch with the digital objects.1 We sense that we can move them or stop them; in other words, interact with them. We are embodied in the digital environment through the sensorimotor experience of touching or moving objects. To sum up, an environment endowed with life entails phenomenological embodiment in that environment; an embodying environment in turn should provide a sense of liveliness. The two ideas, animation and embodiment, unexpectedly, intriguingly work together, becoming interdependent in the new environment. Most important, the interplay between animation and embodiment in digital media hinges on perceptual phenomena of liveliness, which are actually made possible by computing technology, a kind of human invention not originally aimed at providing human experience.

From data to phenomena

A computer, as its name implies, is a machine originally made to compute. So, when and how did computing technology start to shift its focus on to human experience? When did the computer transform from a pure computing machine to an experiential one?

In the nineteenth century an Englishman, Charles Babbage, invented the mechanical computer with an initial view to getting it to do tedious arithmetic in place of humans. It was not until the mid-twentieth century that the first batch of electronic computers was developed to process large amounts of numerical data. The term ‘computation’ at that time seemed to mean strictly numerical data processing. In the latter half of the last century, many inquiries, attempts, and endeavors have been made to transform the object of processing from numerical data to everyday information familiar to humans, such as natural languages, diagrams, pictures, sounds, and moving images. These media materials have been successively encoded as numbers for processing. Today computers or computer-based devices commonly encapsulate and process these media contents, constituting a wide array of nonspecific human activities, including communication, entertainment, creative expression, persuasion, aesthetics, poetics, and others. Machines processing media content include video game consoles, personal or tablet computers, and smartphones, which are part of modern life. In other words, computational devices have become ‘intimate’ companions to some people. Computational media, the virtual container of aforementioned information that is familiar to humans in computational devices, have become pervasive.

Lately, the object of processing has been further transcended, aiming at human-familiar, dynamic, lively phenomena. The term ‘phenomena’ literally means things appearing for humans to view, to perceive, to experience. Many computational devices of today are intended to augment human experience. They give rise to perceptual phenomena that may evoke a sense of life among their users. These phenomena include not only the usual illusion of movement as in animated images but also other apparently biological or natural phenomena of life such as reaction to stimuli, adaptation to changes in surroundings, metamorphosis (rapid shape-shifting), growth in size or population (gradual change), and even breath (rhythmic and persistent change). For example, an application icon in the dock (a special container of user-selected application icons for easy access) of the Macintosh OS X system bounces up and down in response to a user click. In such computer platform games as Super Mario Bros. (1985), a player character suddenly gets transfigure d after ‘picking up’ a special gem or treasure. A few websites dynamically display a graphical representation of social phenomena and track their changes; for example friendship establishment on social networks or exit poll results across geographical election regions. These phenomena are dynamically generated and presented by computational processes, which collectively make digital environments look lively.

Since these computer-generated dynamic phenomena are reminiscent of our everyday, worldly, and bodily experience of life, I call them ‘animated phenomena’. Hence, the aforementioned digital media artifacts not only process data, information, media contents, and user input, but also generate and present animated phenomena through dynamic, responsive, and emergent visuals (and audio too). They evoke everyday experiences of life, and sometimes create unprecedented ones among users. Human users of these digital products are recurrently and concurrently engaged in sensory perception and motor action, as well as other cognitive processes such as interpretation and imagination. In other words, this is embodiment in Merleau-Ponty’s phenomenological sense because animated phenomena in digital media engage with our ‘lived, experiential structures’. They create a situated, perceptual, and even cognitive experience that can only be felt by the embodied user first-hand. The coupling of sensorimotor experience and human cognition particularly resonates with an emergent school of thought in cognitive science: the embodiment of mind, or embodied cognition, which proposes, in contrast to the traditional mind–body dualism, that human thinking is fundamentally inseparable from and dependent upon the physical body and the associated sensorimotor experience. This book is therefore an endeavor to articulate, based on an embodied cognition approach, the emergent kind of technology-mediated human experience, so as to generate a common vocabulary for analyzing existing digital media artifacts and, more importantly, to suggest principles for creating embodying, evocative, and affective new digital designs.

The book: Theory and design

This book is about the human experience of animated phenomena in digital media. It advocates a theoretical and design perspective that emphasizes the pursuit of animated phenomena that evoke in us the everyday experience of life and regards such pursuit as a primary objective of creating digital designs. To this end, the book is organized in three parts.

Part I introduces readers to the diverse everyday examples of animated phenomena. The single chapter in this part characterizes the phenomena, relates associated human experiences to the idea of embodied cognition, distinguishes the proposed topic of investigation, what I call ‘technological liveliness’, from other comparable areas of study, and establishes sensorimotor experience, cognitive processes, and computing technology as the underpinning of this research.

Part II is about theory. It delineates four interrelated perspectives on technological liveliness in four chapters, respectively discussing (1) from a spectator’s viewpoint, how the user of a digital design perceives liveliness (2) how the user’s body interacts with the lively digital environment (3) how one’s mind makes sense of the animated phenomena, and (4) how the user acts like a performer improvising with the computational system to co-create liveliness. Each perspective brings forth a principle for the analysis and design of animated phenomena emerging in digital media.

Part III is about analysis and design. It closely examines a corpus of digital media artifacts from three major genres, namely user interfaces of systems or devices, video games, and digital art, examined in three separate chapters. Every artifact is articulated and analyzed according to the principles derived from Part II. The last chapter of this part illustrates how the proposed perspectives and principles inform new possibilities of creating more embodying, evocative, and affective forms of multimedia design objects.

Readers might be aware that Parts II and III are cross-referenced. The former is organized according to principles with illustrative examples from various genres, while the latter enumerates the corpus, with references to principles developed in Part II. After finishing Part I, readers interested in the theoretical articulation on the basis of perceptual psychology, cognitive semantics, phenomenology, and others in relation to the topic of technological liveliness may move on to Part II, while those less concerned with theories may skip the individual chapters and flip to the chapter summaries of Part II straight away, then choose any chapter in Part III to find out how animated phenomena are manifested in particular design artifacts. Since the two parts are cross-referenced, readers can always jump back and forth if at any moment they want to know more about either theoretical grounding or design thinking embedded in any artifacts.

Hence, this book is intended for multiple audiences. On one hand, for researchers, educators, and students interested in the relationship between art, technology, and philosophy in the digital context, the theory part centralizing the new technology-mediated human experience is particularly thought-provoking. Meanwhile, the related analysis part provides good references for readers to employ the proposed approach in their respective studies. On the other hand, for digital media artists, designers, or developers, the analysis and design part is inspirational and visionary. It encourages them to think critically about digital designs, using another lens focusing on embodied cognition in humans. Moreover, they can trace back to the theory related to a particular design easily and the theories are not genre-specific. Readers practicing solely in one digital media type, for example video games, might broaden their visions by referring to other comparable genres, such as digital art. This cross-referencing feature certainly adds another level of intellectual value to the book.

Finally, the work in this book is expected to serve as a bridge between two ways of thinking. For readers inclined toward humanistic concerns (e.g., art theorists or designers), the book informs possibilities of employing cognitive research results and computational approaches in analysis and creation of meaning. For those with backgrounds in technological research and development (e.g., computer science researchers or programmers), this book provides evidence supporting the vital role of human experience and also humanistic orientations for designing and developing new technologies. At the end, it will bring about an interplay of the two minds.

1

Technological Liveliness

A glance at three animated cases

Animated traffic signals

I came across an intriguing traffic light in Spain some years ago. Pedestrians are supposed to cross the road when a little ‘walking’ green man lights up. The green man walks at first and then runs as the light is about to turn red. The traffic light shows a matchstick man animated in a walking cycle. Images produced by a matrix of light-emitting diodes (LEDs) are displayed successively at a certain speed to achieve an illusion of movement. The green man appears to walk, then run because of the varying playback speed, a technique widely employed in creating moving images.

This case fascinated me. First, it informed me of the ubiquity of animation in today’s digitally mediated environments. Similar traffic lights were installed in many other cities around the world (see Figure 1.1). This traffic light’s primitive graphical form makes intertextual reference to another matchstick man in the classic computer platform game Lode Runner, who ran relentlessly on many Apple II computers circa 1980s. I also can’t resist the temptation to think about the Incredible Hulk in comics (later on TV and Hollywood motion pictures) as the two green men run on the street in their own ways.

Second, this animated version of traffic signals provoked me into questioning its purpose. Undoubtedly, the Lode Runner matchstick man and the Incredible Hulk were animated to entertain the audiences. But what is the purpose of animating a traffic signal? There is no point in entertaining pedestrians. Is the animation created just for the sake of decoration, as a demonstration of advanced electronic technology, or for specific purposes with a certain meaning? Having experienced it, I would say I ‘felt’ a sense of warning and urgency when the little green man ran.

Figure 1.1 An animated ‘running’ green man on a traffic light in Taipei. Images by Lawrence Chiu.

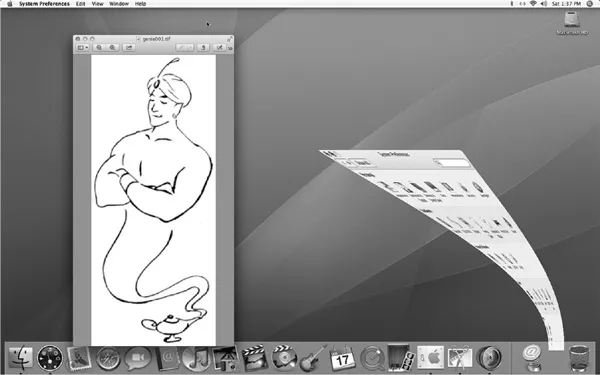

The genie effect

Another thought-provoking case takes place on a graphical user interface (GUI). In the Macintosh OS X system, users may enable a feature called ‘genie effect’ under System Preferences. A window will then elegantly shrink and twirl into the dock (a user-interface element of the system holding a list of application icons for convenient launching) when minimized, ready to be maximized at any time. As the name of the feature suggests, the effect is intended to conjure up the image of a genie, like the one in Disney’s Aladdin (1992), who is trapped in a magical oil lamp and intermittently reveals or hides himself with a twirl (see Figure 1.2).

When first launched, this genie effect amazed many users because of its elegant animation. The mimicry of genie movement was also revolutionary in the field of human–computer interaction (HCI). The visual effect was not created for the sake of utility, because the generative process consumes extra computational power without adding any new function. From a usability perspective, it does not make the interface easier to use or learn either. What is the purpose of animating a GUI window like a genie? Is it just an embellishment, or a spectacle of computer rendering technology? In the design process of an interactive digital product, is there any agenda other than efficiency and usability? As a regular user of the OS X system, I would say the animated effect is a visual metaphor of the philosophy behind the GUI. You can open a standby window instantly, just like summoning a genie. I ‘see’ the spirit of the system, and so I ‘feel’ the charisma of the well received technology brand as a whole.

Figure 1.2 Two genies, one commonly pi...