eBook - ePub

Screen Distribution and the New King Kongs of the Online World

Stuart Cunningham, Jon Silver

This is a test

Share book

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Screen Distribution and the New King Kongs of the Online World

Stuart Cunningham, Jon Silver

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Drawing on comparisons with historical shake-ups in the film industry, Screen Distribution Post-Hollywood offers a timely account of the changes brought about in global online distribution of film and television by major new players such as Google/YouTube, Apple, Amazon, Yahoo!, Facebook, Netflix and Hulu.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Screen Distribution and the New King Kongs of the Online World an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Screen Distribution and the New King Kongs of the Online World by Stuart Cunningham, Jon Silver in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Mezzi di comunicazione e arti performative & Film e video. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Online Distribution: A Backbone History

Abstract: Drawing on industry lifecycle theory – fragmentation–shakeout–maturity–decline – this chapter outlines three waves of market leaders in the online space for the distribution of film and television. The first pioneering wave (1997–2001) was dominated by firms that were small, under-capitalised and ahead of their time. An initial shakeout stage (2001–2006) occurred when the Hollywood Majors moved into the online distribution space. However, they failed to establish profitable business models. A second shakeout stage (2006–) coincided with Apple entering the movie distribution business, and the launch of YouTube. By 2012, the third wave leaders consolidating their market positions in the online distribution space for film and television were YouTube, Apple, Amazon, Netflix, Yahoo!, Facebook and Hulu.

Keywords: film history; screen history; industry life-cycle theory; YouTube, Apple; Amazon; Netflix; Yahoo!; Facebook; Hulu

Cunningham, Stuart and Silver, Jon. Screen Distribution and the New King Kongs of the Online World. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013. DOI: 10.1057/9781137326454.

Looked at from a global perspective firstly, there has been intense experimentation in online distribution seeking to establish viable VOD business models both by and in competition with the dominant major studio players. Hollywood has been driven to undertake expensive and mostly unsuccessful experiments by the hugely successful meeting of global demand for cinema and television programs through informal peer-to-peer platforms. The “burn rate” of venture capital and other investment in the online distribution space has been very high for well over a decade and affords a classic case study of the rapid fires of “creative destruction” in a volatile high-stakes transitionary moment, because few doubt that digital distribution will, eventually, come to dominate both formal exhibition and household consumption in the most broadband-intensive, lucrative territories. The lessons learned from this history, largely of failure, are of benefit to those who are attempting to level the playing field for international and independent content makers globally.

However, almost inevitably, there is a concentration of innovation, in both platforms and business models, in the dominant US hothouse. This means that the backbone history of online distribution must perforce concentrate on the US. The next chapter will explore rest of the world (ROW) developments. It also means that international and independent content creators have either needed to establish direct links with the emerging online distribution market leaders e.g. iTunes, Hulu, Netflix, Amazon (and its European subsidiary LoveFilm) or deal through content aggregators that supply indie product to those majors, or alternatively by self-distributing using open-access platforms, for example YouTube, CreateSpace (with its feeder channel into Amazon Instant Video) and IndieFlix, taking on the task of marketing and monetising their content. There are, of course, exceptions to this general situation. The two most important are: the radical shift very recently that sees major commissioning of content by the emerging market leaders in online distribution, and the one big territorial exception, China – as we will see in the next chapter.

All firms entering the online distribution space during its first decade were confronted with the harsh realities of trying to establish a sustainable business within the context of a volatile, complex and emerging technological environment of what was becoming almost a new industry whose trajectory was unknown. Although some of the barriers they faced have receded, many remain. In the pre-broadband era, the principal factors undermining the first wave of online distribution websites were those common to the majority of commercial ventures in the web 1.0, dotcom era, with the additional challenge that many of their wares were eminently substitutable through extralegal means. Online audiences suffered lengthy download times due to copper wire telephone dial-up connections and primitive compression software for large video files. Large flat-panel computer monitors were not yet available, so the viewing experience on small monitors was poor, and there were only clunky methods of sending film content direct to television sets. There was also a lack of high-quality film entertainment legally available online – most were B-movies or older film or TV content in the public domain. Added to this mix was the rapid shift of emphasis of “ripped” film content to online and informal markets following the Napster-led P2P “creative destruction” of the music business and the fact that software was available to digitise content and upload DVDs and more recently high-definition 1020p quality Blu-rays. A great deal of film or video content could be accessed illegally, anonymously and freely, with just a few clicks of a mouse.

Industry lifecycle and three waves of market leaders

In classical business theory, an industry’s lifecycle is typically mapped in four stages: Pioneering (fragmentation), Shakeout, Maturity, Decline (McGahan et al. 2004). During the pioneering stage, barriers to entry in the industry are low and it is composed of many small start-up firms, seeking to exploit perceived business opportunities. This stage is followed by a shakeout as barriers-to-entry begin to rise, making it more expensive and challenging for aspiring entrants. This stage occurs when large companies either enter or begin to grow within the initially fragmented industry and mergers and acquisitions become more common as aspiring market leaders pursue growth and fight for increased market share by establishing larger operations that can yield scale efficiencies and increased profitability. This precedes the industry’s evolution into a mature stage, typically of long duration, when an oligopoly of companies dominates a market with critical mass and profitability is high and relatively stable. The fourth and final stage of industry lifecycle – decline – occurs when the industry and its major players fail to remain at the cutting edge of innovation and are directly challenged by new innovations, new entrants and/or converging industries that can better satisfy the existing customers needs.

In the online distribution space, during the pioneering stage and the longer shakeout stage that has followed, three waves of firms can be identified as market leaders that sought to develop sustainable business models, which resulted, for the most part, in widespread failure and many casualties – firms large and small, some well-financed and others poorly capitalised, from the US and from the rest of the world. We will cover those from outside the US in the next chapter.

The pioneering stage and first wave of online market leaders: 1997–2001

In the early days of the commercialising Internet, before the dotcom bubble burst, when barriers to entry were low and the future trajectory of the of online video distribution industry was yet to be determined, many start-up companies entered the online video distribution space, most offering short-form video downloads and/or primitive video e-commerce platforms. The highest profile pioneers to emerge during this stage were American firms: I-Film, Atom Films, Intertainer, SightSound, CinemaNow and Pop.com but despite their first-mover advantage most suffered under Christensen’s (1997) “innovator’s dilemma”, being ahead of their time in an embryonic market that was not yet ready. These companies pioneered models and strategies that would later find traction. Their fate is discussed in the next section of this chapter.

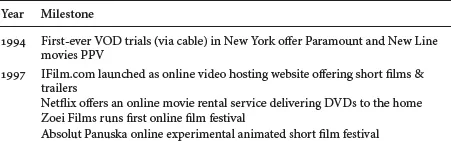

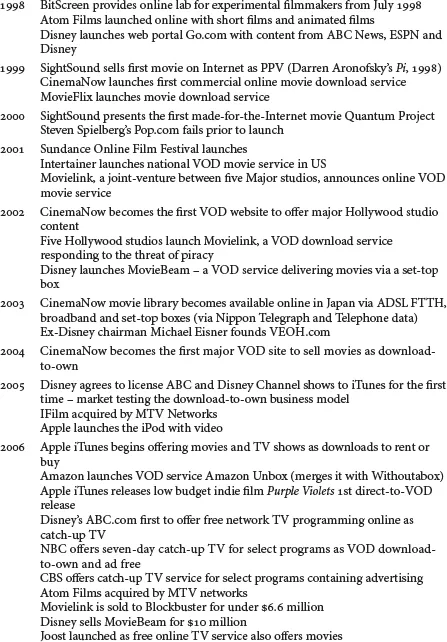

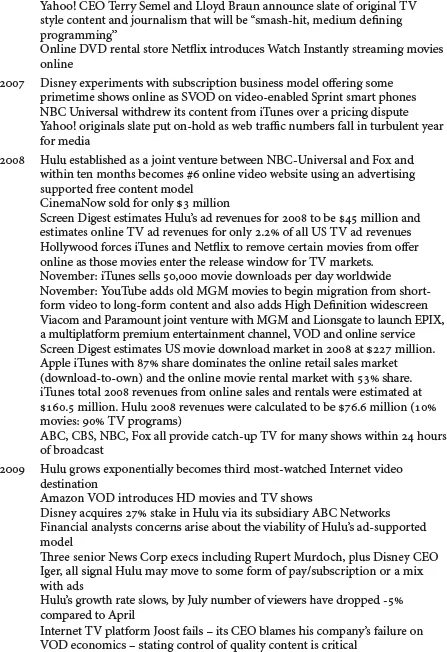

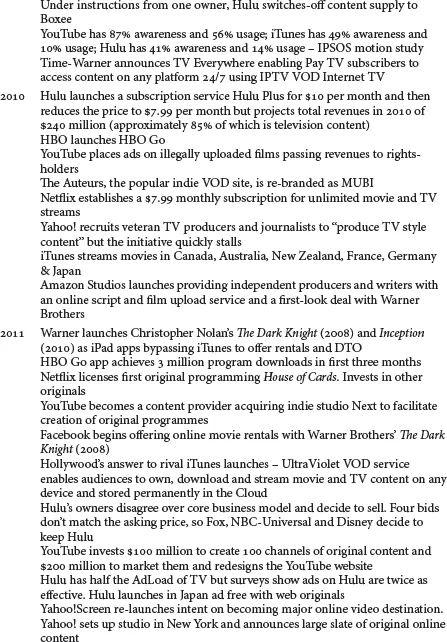

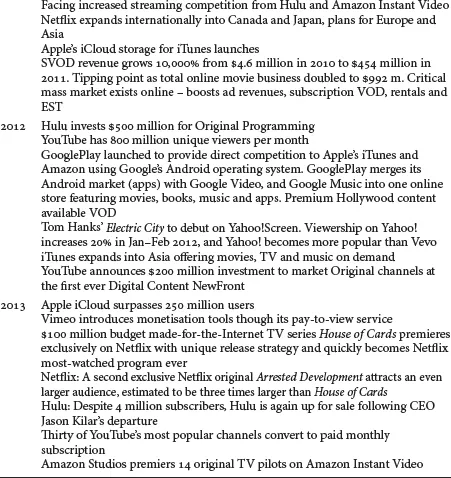

Table 1.1 lists the key milestones in the evolution of the online distribution of on-demand film and TV content via the Internet in the US market from 1997 to 2013.

Table 1.1 US online distribution of screen content, 1997–2013

The shakeout part one, 2001–2006: Hollywood’s failures

A second wave of online market leaders emerged at the start of the shakeout stage around 2001–2002, when Hollywood entered the online distribution and e-retailing space as a strategic response to the intensifying threat of video piracy and the “napsterization of films online” and with the aim of exploiting the opportunities presented by online distribution (Graham 2002).

Sony, Warner, Universal, Paramount and MGM announced a joint-venture – MovieFly (later re-branded Movielink for the actual launch), a virtual video rental store offering films for digital download for a 24-hour period at premium prices equal to rental price-points in bricks-and-mortar video stores. Following the MovieFly announcement, Fox and Disney publicised that they intended a similar co-venture called Movies.com, but it quickly attracted the attention of the US Justice Department on anti-trust grounds following the MovieFly announcement involving five other major studios in a similar joint-venture, so Movies.com was abandoned. Disney however went ahead alone with its MovieBeam service, a digital set top box providing Disney content via the Internet (IPTV) to televisions in the home. Despite media reports to the contrary, these ventures were not only a response to piracy framed as an attempt to protect their intellectual property. The studios were beginning to realise the longer-term commercial potential in online distribution and through Movielink and MovieBeam had hoped to cut out any intermediaries by selling or renting content direct to online audiences within this new distribution channel. In a 2003 gathering of the National Association of Broadcasters, then Disney Chairman Michael Eisner stated:

We are a conflicted industry. Hollywood studios spend enormous sums of money encouraging people to see its films and TV shows and then spend more money devising ways to control and limit how people can see its films and TV shows. Disney is mindful of the perils of piracy, but we will not let the fear of piracy prevent us from fuelling the fundamental impulse to innovate and improve our products and how they are distributed. (quoted in Olsen and Hansen 2003)

By 2005, both Hollywood-owned sites Movielink and MovieBeam had failed to establish viable online business models that matched the commercial expectations of their studio-owners. Despite the availability of “premium” content and the heightened diffusion of broadband Internet within the US, a critical mass of online audiences for legally obtainable premium content was slow to develop, uninspired by the major studios’ offerings online – particularly at price-points matching “bricks and mortar” video stores. Both Movielink and MovieBeam were sold in 2006, for $6.6 million and $10 million respectively – knockdown prices well below the level of investment made by the studios. (All figures in the book are given in $US.)

There were even attempts by Hollywood to use the BitTorrent platform – the bastion of film piracy – to attempt to develop a profitable business model. In2Movies was a joint online distribution venture in Germany, Austria and Switzerland by Warner Brothers and Arbato Mobile (a division of Bertelsmann) that used legal delivery of Warner Brothers movies and TV programmes via a BitTorrent P2P network that was established in 2006 but it closed down in 2008 due to intensive competition in the German market (Screen Digest 2008).

So from 2001 to 2008, Hollywood’s efforts online through Movielink, MovieBeam, In2Movies.com and some other minor experimentation failed to make any significant impact on the uptake of legal downloading services for on-demand movies online or to slow the rate of illegal downloading. When taken together with the failure of Steven Spielberg’s earlier aborted Pop.com (discussed below), Hollywood’s major players lost combined investments of well over $100 million in failed online distribution ventures (Eller and Miller 2000; Reisinger 2007; Robischon 2000; Sandoval 2007).

Undermining Hollywood’s attempts to dominate online distribution were two key factors: firstly, that the core cinema-going audience, aged under 25, was both the heaviest Internet user group and the age group most likely to engage in informal downloading – students had easy access to broadband services in their college dorms; and secondly, that rapid upgrades to technological affordances (faster broadband and better compression software) benefited file sharing P2P sites more rapidly than legal online distribution and e-retail video businesses.

Hollywood had failed to find the right formulas for making sufficient money in the over-the-top online distribution space to justify its investment and ongoing costs. For the first time in the history of the movie business, the Majors voluntarily pulled back from tendencies to vertical integration (studio–distributor–exhibitor/e–retailer) by selling their two online distribution businesses that enabled them to directly push content to audiences without any cut going to a middleman. It is worth remembering that it had taken a two-decade-long anti-trust case by the US Justice Department and finally a US Supreme Court decision in 1948 to force the Hollywood majors to sell their theatre chains and then further Justice Department scrutiny to deter them from trying to acquire and control the embryonic television industry in the late 1940s and early 1950s (Wasko 1994).

During the early shakeout, the pioneering firms faded either because they failed to establish viable business models and folded or were taken over and absorbed by larger companies. Viacom’s MTV Networks acquired both short-form video content sites IFilm (2005) and Atom Films (2006). Sightsound.com had patented and operated the first online video distribution e-commerce platform on which it sold the Internet’s first movie on-demand – Darren Aronofsky’s Pi in 1999 – and had also premiered the first made-for-the-Internet feature film Quantum Project in 2000. It filed suit against Apple for patent infringement after iTunes launched and General Electric then took a 50% equity position in SightSound in 2003. Although no longer an active player in online movie distribution, G.E. continues to pursue Apple in the ongoing SightSound patent infringement lawsuit (Garrahan 2012).

CinemaNow launched the first commercial online movie download service in 1999; it was the first movie VOD service to legally offer downloadable Hollywood content and was also the first VOD site online to offer movies as a download-to-own. The company was sold for only $3 million in 2008 after which new owner Sonic Solutions entered into a strategic alliance with Blockbuster (which had acquired Movielink in 2009), and the two operations were merged before Sonic on-sold the CinemaNow trademark to BestBuy. Intertainer, which launched an online movie service in 2001, was another early VOD platform during the pioneering stage of the new industry. Comcast, Intel, Sony, NBC, Microsoft and Qwest all became investors in the company.

Steven Spielberg’s Pop.com had planned to produce short films featuring A-list Hollywood talent and distribute them online but it folded prior to its launch despite burning $50 million in establishment costs. It failed because of the classic innovator’s dilemma – it was ahead of the market. It is notable that FunnyorDie.com is one of a number of commercially successful online sites in 2013 that uses the same basic formula that Spielberg had envisaged for Pop.com. Business Week noted, on Pop.com’s demise, “Too few folks are sufficiently wired to get superfast broadband connections to watch Hollywood’s Internet fare, and therefore too few people are willing to pay anything for it” (Grover 2000).

The shakeout part two...