eBook - ePub

Creativity and Mental Illness

The Mad Genius in Question

S. Kyaga

This is a test

Share book

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Creativity and Mental Illness

The Mad Genius in Question

S. Kyaga

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Is there really a thin line between madness and genius? This book provides a thorough review of the current state of knowledge on this age old idea, and presents new empirical research to put an end to this debate, but also to open up discussion about the implications of its findings.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Creativity and Mental Illness an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Creativity and Mental Illness by S. Kyaga in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medizin & Psychiatrie & geistige Gesundheit. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Medizin1

Introduction

We have many books and articles on great men, their genius, their heredity, their insanity, their precocity, their versatility and the like, but, whether these are collections of anecdotes such as Professor Lombroso’s or scientific investigations such as Dr Galton’s, they are lacking in exact and quantitative deductions. Admitting that genius is hereditary, or, what is more doubtful, that it is likely to be associated with insanity, we have only the ‘yes’ or ‘no’ as our answer. But this is only the beginning of science. Science asks how much? We can only answer when we have an objective series of observations, sufficient to eliminate chance errors.

James Cattell in ‘A Statistical Study of Eminent Men’ (1903)

Is there really a thin line between madness and genius? While many of us inherently are inclined to believe so, history is full of ideas that science has disproven. The aim of this book is to discuss the present state of knowledge on the alleged association between creativity and mental illness: if there is a true association, and if so, how this association is manifested.

The mad genius link

Comments on the mad genius link have been made almost as long as Western society itself. Often referred is Aristotle’s (384–322 BC) question put in Problemata XXX, written by his pupil Theophrast (371–287 BC), ‘Why is it that all those who have become eminent in philosophy, politics, poetry, or the arts are clearly melancholics and some of them to such an extent as to be affected by diseases caused by the black bile?’ (Aristotle, 1984). This quote was later modified by Seneca the Younger (4 BC–AD 65) citing Aristotle to have said, ‘No great genius has existed without a strain of madness’ (Motto and Clark, 1992). Later times saw the poet John Dryden allude to this quote, arguing that, ‘Great wits are sure to madness near ally’d; and thin partitions do their bounds divide’ (Motto and Clark, 1992). A famous quote by the romantic poet Samuel Coleridge, was that his madness was, ‘a madness, indeed celestial, and glowing from a divine mind’ (Sanborn, 1886). The end of the ninteenth century also saw the birth of more scientifically inclined studies on the alleged association of creativity and mental illness. Of these, Cesare Lombroso’s study had an enduring impact on public apprehension (1891). However, as can be found in the quote by James Cattell above (1903), Lombroso fell into disrepute, and his work has since been considered as a mere collection of anecdotes.

Research in creativity has expanded considerably since then (Kaufman and Sternberg, 2010). Today a multitude of questions maintain the interest of an ever increasing number of researchers focused on different aspects of creativity. Creativity, as an object of study, is a multifaceted entity that by nature is translational. Thus, creativity is approached in a number of disciplines, such as psychology, sociology, pedagogy, history, economy and, more recently, by genetics and neuroscience (Kaufman and Sternberg, 2010). Nonetheless, the interest in the old question of the mad genius link has been upheld both within academia, and what is perhaps more uncommon for a scholarly field, within the public (Silvia and Kaufman, 2010).

This is maybe the reason why researchers who are otherwise stringent and subjected to rational thought, may sometimes be carried away when discussing the nature of creativity and psychopathology. The field is characterized by authors having taken completely contradictory positions arguing everything from mental illness having nothing to do with creativity to other authors arguing for it being deeply entwined. Many times these arguments are passionate and often less founded in empirical studies (Silvia and Kaufman, 2010).

Early empirical studies on creativity and mental illness

Lombroso’s study of genius linked to madness was contemporary with other attempts to approach the question of genius with a burgeoning empirical approach. Francis Galton’s Hereditary Genius – An Inquiry into its Laws and Consequences published in 1869 was a comprehensive attempt to investigate hereditary aspects of exceptional behaviour (1869). In English Men of Science: Their nature and nurture published in 1874 (1874), Galton concluded with a reference to Thomas Carlyle that, ‘It is maintained by Helvetius and his set, that an infant of genius is quite the same as any other infant, only that certain surprisingly favourable influences accompany him through life … I should as soon agree as with this other – that acorn might, by favourable or unfavourable influences of soil and climate, be nursed into a cabbage, or the cabbage-seed into an oak’ (p. ix).

Thus, much of the early studies into genius were driven by the idea that certain inborn traits were associated with extraordinary gifts. However, in 1928 Wilhelm Lange-Eichbaum argued for a sociological perspective on the definition of genius. In an English shortened version of his vast Genie – Irrsinn und Ruhm published in 1931, he claims that, ‘The one who is not yet called a genius is no genius’ (Lange-Eichbaum and Paul, 1931, p. 67). Yet, he says, ‘It cannot be a chance matter that among geniuses the healthy constitute a minority’ (p. 125).

Rise of creativity research

Although there had been early attempts to characterize the creative process, it was Joy Paul Guilford who introduced creativity as an important field for psychological research. In his 1950s inaugural address to the American Psychological Association, Guilford characterized creativity as the most important resource available to human society (1950). He told that efforts to promote creativity would pay high dividends for society as a whole. Guilford also promoted the use of psychometrics, the measurement of creativity objectively, and argued for divergent thinking being at the heart of the creative process. Divergent thinking does not result in one right answer but rather in a number of possible solutions to an open-ended problem. Although Guilford’s idea of divergent thinking as a common factor for creativity has been debated in recent research, his influence still carries weight in the field (Runco, 2010).

Contemporary studies on the mad genius link

Increasingly studies using sound methods have investigated the question of a link between genius and madness or more specifically creativity and psychopathology.

Nancy Andreasen, for example, demonstrated increased risk for affective disorders (depression, bipolar disorder) in general and for bipolar disorder in particular in 30 creative writers at the University of Iowa writers’ workshop, compared to healthy controls (1987). Similarly, Kay Redfield Jamison found increased risk for affective disorders in 47 British writers (1989). Arnold Ludwig used reviews of biographies published in the New York Times book review between 1960 and 1990 as selection criteria, identifying 1005 eminent individuals (1992, 1995). Based on their biographies, he found an overrepresentation of bipolar disorder, schizophrenia-like psychosis and depression in the creative arts group.

The above studies are often cited in defence of the alleged association between creativity and mental illness. They have, however, been seriously criticized by some authors opposing the association between creativity and mental illness (Rothenberg,

1995). Judith Schlesinger goes as far as to call the whole association a hoax (2009, 2012). Schlesinger’s main criticism is that the authors of these studies both selected study subjects, and in general themselves made the diagnoses without support in recognized diagnostic manuals. This would make the results open to both bias and difficulties in generalization. While part of Schlesinger’s criticism is relevant and sound scepticism is always advised, there is a surprising neglect in Schlesinger’s approach to discuss or even mention the other roughly hundred empirical studies addressing the association between creativity and psychopathology.

Some of these other studies have evaluated creativity in people with manifest psychopathology. Santosa et al. compared individuals with bipolar disorder, unipolar depression, healthy creative, and non-creative controls using the creative inventory Barron-Welsh Art Scale (BWAS) (2007). They found that people with bipolar disorder and healthy creative controls scored higher than those with unipolar depression and non-creative controls. Another study reported increased creativity in 40 American adults with bipolar disorder compared with healthy controls using the same instrument (Simeonova et al., 2005).

To avoid bias caused by the debilitating effects of mental illness, some studies have included relatives of those with psychiatric disorders. For example, Karlsson investigated 486 male relatives of people with schizophrenia born in Iceland between 1851 and 1940 (1970). Compared with the general population, the relatives were more often represented in a listing of prominent people. There was also a significant increase in those specifically successful in creative endeavours, although the number of people included were small.

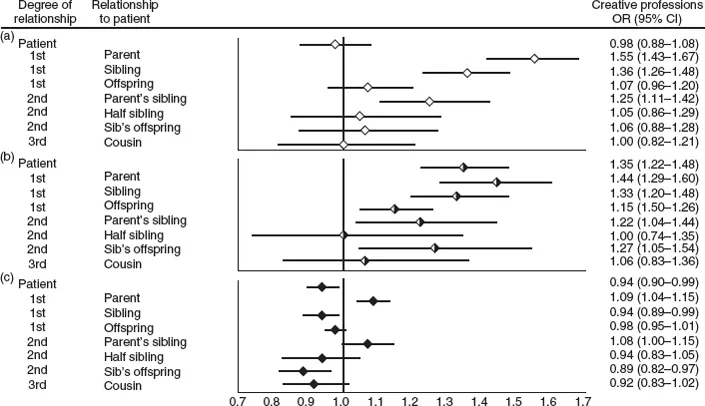

Because most of earlier studies have relied on biographical data of eminent individuals or small cohorts of patients, we initiated a project using large scale population-based methods to investigate the association of creativity and psychopathology. In the first study ~300000 patients with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and unipolar depression, and all of these patients’ healthy relatives (first, second, third degree), were investigated with regards to their representation in creative professions (Kyaga et al., 2011). Creative professions were defined as artistic and scientific occupations. Results demonstrated a significant increase of creative professions in patients with bipolar disorder and relatives of patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder (Figure 1.1). No associations were found for patients with unipolar depression or their relatives. Common for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder is that they are psychotic disorders. Psychosis is a severe symptom consisting of an aberrant comprehension of reality (Box 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Study on ~300000 patients demonstrating an increased occurrence of creative professions in patients with bipolar disorder (A) and healthy relatives of patients with schizophrenia (B) and bipolar disorder compared to healthy controls.

Note: No associations were found for patients with unipolar depression (C) or their relatives. An odds ratio (OR) higher than 1 implies an increased occurrence, whereas lower than 1 implies a decreased occurrence. Creative professions were defined as artistic and scientific occupations.

Source: Kyaga et al., 2011.

The results of the first study was later followed up in a larger set of ~1.2 million psychiatric patients and their relatives including most different psychiatric disorders (Kyaga et al., 2013). Results affirmed previous associations, but also suggested an association for relatives of patients with anorexia nervosa and possibly autism. Most other psychiatric diagnoses, such as unipolar depression, anxiety disorders and substance abuse were associated with a decrease in the likelihood of holding creative professions. However, authors were specifically affected with most psychiatric disorders and also suffered a ~50 per cent increase in the risk of committing suicide.

Box 1.1 History of psychiatric diagnoses

Research into the clinical manifestation (phenomenology) of psychiatric disorders has a long history. The word disorder is derived from the French word désordre, meaning disorder, disturbance or chaos. This deviance from norm is traditionally seen in relation to a statistical norm (e.g., population mean), cultural norm or the individual self.

Modern definitions of psychiatric disorder rests heavily on the work of Emil Kraepelin (1856–1926). In his Compendium der Psychiatrie published in 1883, he argues that psychiatry is a branch of medical science that should be investigated by observation and experimentation like other natural sciences. He proposed that by studying case histories and identifying specific disorders, the prognosis of specific mental illnesses could be made, after taking into account individual differences in personality. Kraepelin divided psychosis (then meaning severe psychiatric disorder) into two distinct forms, acknowledged as the Kraepelinian dichotomy: manic depression and dementia praecox. Manic depression corresponded to more contemporary definitions of recurrent major depression and bipolar disorder, while dementia praecox was later redefined by Eugen Bleuler (1857–1939) as Schizophrenia. The later was to stress that dementia praecox did not necessarily lead to mental decline, which was initially proposed by Kraepelin. For a description of the phenomenology of the most common psychiatric disorders, please refer to Box 1.2.

Classifications systems

Contemporary psychiatry uses one of two systems to classify psychiatric disorders. These are the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD) or the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). Both these systems have been continuously updated. The ICD, presently in its tenth version (ICD-10) is provided by the World Health Organization (WHO), which is a branch of the United Nations (2004). The main office is in Geneva, Switzerland. The first version headed by the WHO was published in 1948 (ICD-6), which was based on work, however, by the Frenchman Jaques Bertillon presented at the International Statistical Institute in 1893 (2010). The current ICD version was accepted in 1990 and consequently adopted by member countries during the following years. It is the internationally accepted standard for diagnosis of diseases and used for epidemiological and statistical purposes.

In parallel with the development of the ICD, the 1970s saw a growth of interest in refining psychiatric classification worldwide (1993). Several national psychiatric organizations developed specific criteria for classifications in order to improve diagnostic reliability. In particular, the American Psychiatric Association developed and disseminated its Third Revision of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-III-Tr) (American Psychiatric Association. Task Force on ...