eBook - ePub

The Philosophy of Life and Death

Ludwig Klages and the Rise of a Nazi Biopolitics

Nitzan Lebovic

This is a test

Share book

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Philosophy of Life and Death

Ludwig Klages and the Rise of a Nazi Biopolitics

Nitzan Lebovic

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Some of the first figures the Nazis conscripted in their rise to power were rhetoricians devoted to popularizing the German vocabulary of Leben (life). This fascinating study reexamines this movement through one of its most prominent exponents, Ludwig Klages, revealing the philosophical-cultural crises and political volatility of the Weimar era.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is The Philosophy of Life and Death an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access The Philosophy of Life and Death by Nitzan Lebovic in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & European History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

From the Beginning of Life to the End of the World

In May 1932 Ludwig Klages, a pioneer of modern vitalism and of graphology, published the third and final volume of Der Geist als Widersacher der Seele (Spirit as the adversary of the soul). An autodidact, Klages compiled in this book almost 20 years’ worth of research and publication. Developing a system he hoped would remedy a world gone mad, Klages began by rejecting all limits and boundaries, proposing in their stead a philosophy based on “life’s flow” (Strom des Lebens) and “the reality of images” (Wirklichkeit der Bilder). The two concepts were heavily embedded in the jargon of Lebensphilosophie, a concept identified with Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900), Wilhelm Dilthey (1833–1911), and Henri Bergson (1859–1941) in the late nineteenth century. All three philosophers, and Klages in turn, tried to reassess the contribution of German idealism to contemporary culture. In so doing, they rejected the notion of a scientific telos and idealist truth value in favor of an “aesthetic fundamentalism.”1 While Nietzsche, Dilthey, and Bergson are considered to be “serious” philosophers, Klages is considered by the historians and thinkers discussed in this book as the principal father of Nazi rhetoric and a vital promoter of the irrational opposition to Enlightenment values.

Klages’s case is a paradigmatic one. Like other radical conservatives, he observed Nazism as a movement of the masses that served as a temporary transporter of much deeper philosophies. Like other opportunists, he considered using Nazism for his own purposes, and then found himself cheated by it and betrayed by his fellow party representatives. As I will show in this chapter and beyond, the heart of Klages’s agreement with the Nazi credo rested in its anti-Semitic messages. Klages identified Judaism and its forms as objectionable on a biological basis but also as a philosophy and a form. His philosophical interest did not make his virulent anti-Semitism easier to absorb. He adopted the stereotypes of Jews readily enough, but he was willing to ignore those stereotypes when he found individual Jews to be more faithful to the discourse of Leben, against their “Molochism.”2 Interestingly enough, on the occasions when Klages expressed intellectual admiration, it was more often for Jews than for non-Jewish Germans. Three Jews—Theodor Lessing, a childhood friend, and Karl Wolfskehl and Richard Perls, two Jewish disciples of Stefan George—made the most radical impression on him during the first three decades of his life, and he admired Melchior Palàgyi, a Hungarian Jewish philosopher and physicist, in the second half of his life. Indeed, anti-Semitism seems too simple an answer in his case. Not because it is not a possibility at all, but because it cannot be comprehended from its later interpretation and application by national socialism. The defining conflicts of Klages’s early adulthood, with Theodor Lessing and Stefan George, indicate just how important this issue was for Klages, well before he encountered a more disciplined theory of race.

This significance, however, has no bearing on the question of political and moral responsibility; in what follows I shall attempt to historicize and move with Klages and his thought, not against it, as if from the point of view of an anachronistic judgment. As a result, this chapter, and the book as a whole, will illustrate a set of themes by way of Klages’s relationships with those whom he thought were representing them: Stefan George and his circle;3 Theodor Lessing, the faithful Jewish and idealist childhood friend; and the love affair with the Bohemian feminist Franziska zu Reventlow and her ironic commentary about the “jargon of life superlatives” in Munich.4

If Klages can be taken to represent Lebensphilosophie, an historical and theoretical peek is required to pursue the gradual politicization and Nazification of Germanic life. Otherwise, one could easily miss the intensity and gravity with which Klages and his fellow Lebensphilosophers used the concepts of life and form, whole and immanence, lifetime and living experience.

1. The life before the life: Klages, Lessing, and George in the 1890s

Born in Hanover in 1872, Ludwig Klages lived most of his youth with a younger sister, an authoritative father, and a sentimental aunt.5 His mother died giving birth to his sister. His father, a salesman and a former military officer, tried to provide Klages with the education and discipline that would allow him to climb the social ladder. According to Klages’s later recollections, his father relied on a tough approach in dealing with his intelligent son. Perhaps because of the trouble he had communicating with his father, in childhood Klages developed a fantasy world largely shaped by the romantic literature of the period. In the unpublished notes for an autobiography, he proudly described his childhood visions, narrating his tale in the third person: “When he was far from other people, and away from school assignments, . . . the cloth of his body was torn and filled with his magical soul: the chairs in the room started to talk, the tapestry on the walls was cut into faces.”6

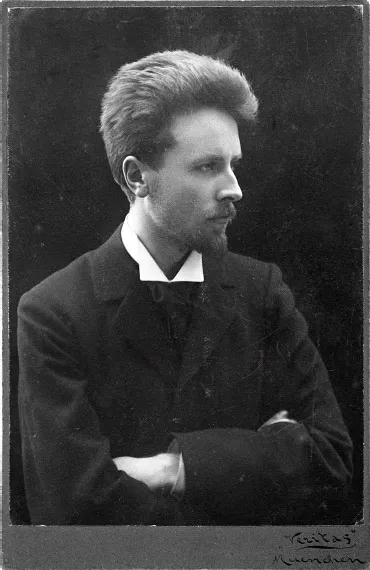

Figure 1.1 The portrait of Ludwig Klages as a young man, ca. 1895. Photo: Veritas Munich. DLM: Ludwig Klages Nachlass.

At his high school, Klages befriended Theodor Lessing, a young Jewish student strongly drawn to romanticism. (Lessing already possessed a remarkable intellectual curiosity and would later become an important contributor to Lebensphilosophie himself.) The literary and fantasy world the two shared blurred the social differences between them. Lessing’s family was richer, thanks to his father’s medical clinic; Klages did better at school. But society would intrude. According to Lessing, “Ludwig’s father did not view his son’s fraternization with ‘Juden’ [Jews] as acceptable.”7 In spite of their own rocky relationship, Klages later came to agree with his father’s anti-Semitism. He commented on Lessing’s memoirs, published after his old friend’s death, “The most grotesque statement made by Lessing is that he was a ‘friend of the house.’ In fact, he was never welcomed, and finally was prohibited from visiting. Klages senior could not tolerate—‘smell’ was his expression—Lessing.”8 The correspondence between the two confirmed Klages’s recollection. In a letter to Lessing written in 1890, Klages announced: “Your name is banned in our house. It is seen as a satanic residue of hell itself, a despicable stain.”9 Here and in other letters written during the early 1890s, Klages tells Lessing how he fought to preserve their friendship in spite of his father’s disapproval.

In 1891 Klages moved to Leipzig, where, following his father’s instructions, he decided to study industrial chemistry. But the lively artistic and philosophical scene in Munich presented an irresistible temptation. Upon arriving in Munich in 1893, he lived for a short while at the same boardinghouse as Stefan George. George, a decade older than Klages and already beginning to enjoy the local fame his poetry and mysticism brought him, befriended the new arrival. Two years later, Lessing followed Klages to Munich. Klages had showed George some of his friend’s writings, but the response was not positive: “Stefan George thinks that there is too little that is positive in your book.”10 In a slight every author feels keenly, George remarked: “The author must be very young.”11 Lessing wrote about the strain of their friendship in his autobiography, “Klages’s friendship with Stefan George was the first cause of our alienation.”12 Rebutting another section of Lessing’s posthumous book, Klages insisted, “Lessing’s report about his meetings with George is full of lies. It was Klages that showed Lessing’s writings to George; the latter was nauseated and utterly refused to meet the author.”13

As Klages’s study of chemistry—inspired equally by his father’s insistence as by Goethe’s metaphors—could not serve as a vehicle for the ideas he developed under the influence of Stefan George, he switched to a program in psychology and philosophy. His academic mentor was Theodor Lipps (1851–1914), a philosopher and expert in psychology and aesthetics, who theorized an understanding of empathy on the basis of its psychological appearance or expression. In developing his aesthetics, Lipps focused on the need to systematize the notion of inner experience (Wissenschaft der inneren Erfahrung) on the basis of physical and apparent forms.14 Klages translated this inner experience first in pure, aesthetic terms; even as he caved to his father’s pressure and prepared his thesis in chemistry, he contributed a number of poems and brief articles to George’s journal, Blätter für die Kunst (literally, Pages for the arts) that reflected the great interest he took in both Lipps’s philosophy and George’s poetry. Lipps and George served as authority figures—Klages had little use for his father, who deeply resented his son’s academic rebellion. Nevertheless, on July 1, 1900, Klages received his doctorate in philosophy, after altering his topic to suit a philosophical discourse and against the explicit wishes of his father.

Klages’s friendship with Lessing was a casualty of Klages’s intense commitment to the new ideas he encountered in Munich. Lessing’s description of the end of the relationship bears all the marks of the sort of romantic schoolboy alliance familiar to readers of Thomas Mann’s stories: “When we separated in 1900, I sent back many of Klages’ letters . . . He later destroyed every sign of our friendship . . . It is his great pride that made him see that all he hated in himself, the entirety of his will to power [seinen Willen zur Macht], his indoctrinated pride, his cold drive . . . everything was related to my name and the sign of my blood and what is called the marks of my race. And the more Ludwig Klages felt that this friendship had been an error, [the more he wished to] rip off this holy bond, and the more he felt he needed to forget me.”15 As Elke-Vera Kotowski has recently shown in the only comprehensive narrative of the relationship, the friendship managed to survive until their radically different political and social paths drew the men apart. Close friendship, strong competitiveness, self-distancing, and enmity characterized the course of Klages’s relationship with Lessing. A close attachment ended in radical expressions of hatred and racial stereotyping.16 A very similar course would also characterize his relationship with Karl Wolfskehl, the best-known follower—Jewish and pro-Zionist—of Stefan George.

Klages appears to have been happy to let his new Munich acquaintances blot out all thought of Lessing. Later, when he was asked about this friendship, he either ignored the question or explained it as a youthful error. But in time two disturbing events joined Klages’s name to that of Lessing. The first was the incident known in the press as the Lessing case. The second was Lessing’s murder and the posthumous publication of his memoirs.

In April 1925, while teaching at Hannover’s Technische Hochschule (technical college), Lessing published an article against Paul von Hindenburg’s presidency in a Prague journal. Hardly an exercise in sober reasoning, the article described Hindenburg as “a servant . . . a symbol of representation, a question mark, a zero. One might say: better to have a zero than a Nero. Unfortunately history shows us that behind every zero a crafty Nero is always hiding.”17 The Hannover newspaper picked up the article, revised it in a sensationalist vein to emphasize the more scandalous passages, and silently omitted the more reasoned parts. The reactions were outraged and violent.

Hannover’s local administration encouraged the student organization to respond to Lessing’s diatribe. The chancellor at the school kept his distance from the affair for fear of being incriminated as an assistant to an unpatriotic Jew. With the support of the vice chancellor, who orchestrated much of the protest, the students called on the chancellor to fire Lessing immediately. After a final meeting with the reluctant chancellor, Lessing decided to leave Germany for Prague. Minutes kept at the student meetings and at Lessing’s meeting with the chancellor re...