![]()

Part I

The Role of Creative Ignorance as a Willing Action

1

Why Is Creative Ignorance Important?

Formica, Piero. The Role of Creative Ignorance: Portraits of Pathfinders and Path Creators. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015. DOI: 10.1057/9781137492470.0007.

With good reason, ignorance is generally ill-regarded. However, there are opportunities for observing ignorance from other perspectives, brought to light not only by researchers but also by the popular media. Introducing, on 17 August 2014, the BBC Radio 4 programme ‘Something Understood’, which addresses each week a different and wide range of topics under the guidance of Mark Tully, a long-serving and highly experienced BBC journalist, the radio announcer said that in this particular programme, ‘On Ignorance’,

Mark Tully invites us to accept our own ignorance as a first step on a voyage of discovery, taking his lead from Socrates’ well-known thought that, ‘The only true wisdom is in knowing you know nothing.

There is a lack of awareness of creative ignorance, that which by design comes after, not before, knowledge and unlocks otherwise unthinkable paths of economic growth and social development, and is even less well-known for being revolutionary. As humanity struggles supposedly to eradicate ignorance, those who lobby for knowledge and expert groups push creative ignorance into a corner. It was not thus in the ancient world. Scholars and wise individuals of times past were those who pioneered the idea of creative ignorance. In today’s world, we need more than ever ‘Homines Novi’, New Men, who enable us to exploit the strengths of creative ignorance and overcome the weakness of accrued knowledge.

Creative ignorance contains a good dose of unreasonableness. At the end of the 1980s Charles Handy, acclaimed scholar of management, wrote that,

We are entering an Age of Unreason, when the future, in so many areas, is there to be shaped, by us and for us; a time when the only prediction that will hold true is that no predictions will hold true; a time, therefore, for bolding imaginings in private life as well as public, for thinking the unlikely and doing the unreasonable. (Handy, 1989)

Equally, others have pondered on the wisdom of ignorance:

Our wretched species is so made that those who walk on the well-trodden path always throw stones at those who are showing a new road. (Voltaire, Philosophical Dictionary)

I am looking for a lot of people who have an infinite capacity to not know what can’t be done. (Henry Ford)

The adventum

Engaged in scientific research or involved in the world of business, what decisions do we take once we reach the frontiers of knowledge? Do we attempt to overcome the boundaries of incomprehension by using acquired knowledge and past experiences? Stripped of the baggage of our existing knowledge, do we continue the quest for new knowledge by embracing creative ignorance? Do we embark upon a project that takes us away from John Milton, to follow in the footsteps of William Shakespeare as interpreted by William Hazlitt (1778–1830)? This English literary critic and essayist wrote,

Or, perhaps, do we invoke God or deities, as scientists of the highest calibre such as Isaac Newton, Pierre-Simon de Laplace and Christian Huygens sometimes did? Neil deGrasse Tyson (2005) captured this nicely in recalling the invocation of Newton to God:

There are many questions preying on our minds when we embark on the passage of discovery of paths to tread. In the course of our adventure, what might befall us, or what we want to happen? Will our adventum (‘venture’) be as we had supposed? Will it be wider, narrower or more different than we ever thought imaginable? To answer these questions, each explorer will use the tools available in their tool kit. According to attitudes, motivations, capabilities and circumstances, it may be the tool kit of knowledge or that of creative ignorance. There are those who want to master the attributes of knowledge at the highest level in order to find the right direction. There are others who, like Socrates, have learned that ignorance is the very thing that makes them wiser than the others, that gives them the capacity to make creative decisions about where and when to go. In times of major transformation, this second species of individuals is suddenly revealed, appearing almost as a major mutation of human behavior. These, the ‘hopeful monsters’ as Goldschmidt (1940) called them—albeit in a completely different context—bring the hope and promise of changing the rules of the game. In doing so, they would plot a set of trajectories quite unlike those that had previously prevailed and would give voice to new players. When the ‘monsters’ appear, the Very Knowledgeable Persons desperately seek support in someone who, like Dante’s Virgil, possesses the reason and decisiveness required to repel their attempts to create the conditions for the birth of a new world order.

It seems somewhat obvious that there is a direct and linear channel of communication between knowledge and ignorance—a feeling like that of a pair of tango dancers. Where the one is lacking, the other appears. When I know that I don’t know, then I rally my energies to close the gap. This is in fact what researchers and entrepreneurs do when they reach, respectively, the borders of their scientific and entrepreneurial knowledge. However, matters begin to attain both a higher level of difficulty (they become more complicated) and complexity (a greater number of components comes into play) once two causes arise, together or separately. The first cause is the ‘not knowing of not knowing’. That one may not have a mind open enough to be able to get rid of past experiences and biased reasoning, and which is not affected by and vulnerable to external criticism, as well as being ill-informed, must also all be taken into account.

It can also happen that closed-mindedness can have such an influence as to cause us to exchange one thing for another. As described in The Little Prince by Antoine de Saint Exupéry (1943), the boa constrictor mistaken for a hat is a sign of unimaginative minds for which the only possible explanation is their limited perspective. The protagonists of The Little Prince make us appreciate a child’s mind full of imagination and empty of those past experiences that are the sources of stereotypes and prejudices. Exupéry points at grown-ups as having narrow minds. What is certain is that for them the journey from knowledge to creative ignorance is a metaphorical walk on hot coals: they then come to see that knowledge has more or less relevance depending on who is its bearer. Returning to the story of The Little Prince, the Turkish astronomer who, at the International Astronomical Congress in 1909 presents with some brilliance his discovery of an asteroid, is ignored by the audience of scientists, for he was wearing the traditional clothes of his country; and this is why ‘A Turkish dictator made a law that his subjects, under pain of death, should change to European costume. So in 1920 the astronomer gave his demonstration all over again, dressed with impressive style and elegance. And this time everybody accepted his report’ (de Saint Exupéry, 1943, Chapter IV). Because fantasy and reality are mirror images of each other, the episode of the Exupéry’s Turkish scientist has been replicated in the reality of academic life a thousand times and more. We find evidence of this in academic elitism and hubris (‘unchecked intellectual arrogance’), as highlighted in all their harshness by Professor Martin Anderson (1992): two mindsets that give so much credibility to the knowledge of their bearers. In addition, we must consider the fact that knowledge is naturally inclined to search for errors with a view to removing them, making use of analysis, investigation and expertise. Creative ignorance, for its part, constantly searches for the inner nature of things through intuition.

Let us imagine for a moment that we can build a box that includes all of our own knowledge, beliefs, habits, ideas, customs and social behavior, but not ignorance. We call this artefact ‘Culture’—that is, our personality or ‘human operating system’, as defined by Bill Tobin, a consultant at Strayer Group in Silicon Valley. The code of personality rejects ignorance. Knowledge is light; ignorance is opacity and darkness. In ancient times, the Egyptians worshiped Ptah, the god of knowledge and learning, of creation, the arts and fertility. In the epistolary novel ‘Augustus’ (Williams, 1972), the American author John Williams mentions Athens as ‘the mother city of all knowledge’ in his imaginative creation of the Roman poet Horace’s thoughts and stages ‘an Italian Orpheus [whose] love was no woman; his Eurydice was knowledge’. Philostratus, a Greek sophist of the Roman imperial period, in his book The Life of Apollonius of Tyana (Jones, 2005) ascribed to gods, as possessors of all knowledge, the ability to pierce the veil that covers the future. And in Dante’s Inferno ignorance is, together with impotence and hatred, one of the three characteristics attributed to Beelzebub, one of the seven princes of Hell. In short, without knowledge there are no paths that we can find or create, and then tread. As stated in the poem Ithaca by Constantine Cavafy (2007),

But, consider this: if lacking a particular type of ignorance were not possible, would that make us feel quite adventurous?

The way of treating ignorance in early times was to separate the ignorance of the foolish from that type of a healthy Socratic, ‘self-aware’ kind of ignorance which Saint Augustine dubbed as mindful, learned ignorance. Down the centuries that followed such a concept was reaffirmed by the humanist, mathematician and astronomer Nicolaus Cusanus (1401–1464) in his work De Docta Ignorantia (On Learned Ignorance) where, in the words of Philippe Verdoux (2009), he held that ‘ . . . ignorance and knowledge are not wholly distinct epistemic phenomena, but combine and overlap in interesting ways . . . . The more [a wise person] knows that he is unknowing, the more learned he will be. In other words, learned ignorance is not altogether ignorance, but a kind of knowledge or wisdom’; by the German philosopher Johann Gottlieb Fichte (1762–1814), who argued that down the road towards the conquest of ‘not knowing’ is an infinite journey; and by the American educational reformer John Dewey (1859–1952) who explained that there is a type of ignorance—he called it ‘genuine’—which is ‘profitable because it is likely to be accompanied by humility, curiosity and open-mindedness’ (Dewey, 1933).

In our lifetime, Hans Magnus Enzensberger, one of Europe’s leading writers and critical thinkers, states that the acquisition of knowledge requires gestures of refusal. In order to see something you have to give up many things to see. Ultimately, we start from a position of ignorance to create new branches of knowledge beyond, or to replace, those that already exist. Those who take this course of action are aware of the extent of their ignorance: in the words of Confucius, this awareness is their true knowledge. With existing knowledge, one keeps delving far more deeply into the same pit. In the Internet age, a shroud of mist obscures learned ignorance—that is, the creativity from which all things new emanate. Thanks to the Internet, it seems that we are all knowledgeable, confusing facts and figures (information) with cognition (knowledge) as a result. Even when information and knowledge are kept apart, the latter is the breath of our intellectual life of such force as to stifle creative ignorance.

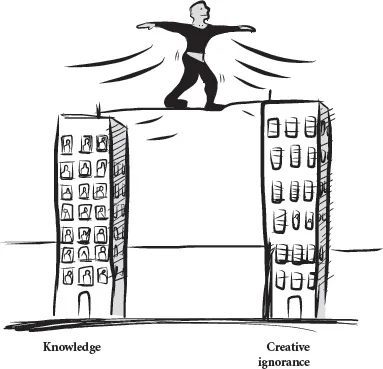

The Philosopher’s Path and the tightrope walker

Knowledge gained enables suitable ways to pursue an approach to incremental innovation to be found. The smart path to take looks like The Philosopher’s Path in the northern part of Kyoto’s Higashiyama district. This is the path of meditation, with flowering cherry trees in springtime. Nishida Kitaro (1870–1945), a prominent Japanese philosopher, practised meditation while walking this safe and enjoyable route. After the blossom comes the harvest, not always equally abundant. Similarly, the incremental approach to innovation prompts meditation to find methods that lead to blossoming and harvests better and more abundant year after year. Ultimately, however, it is one and the same topic: cherry trees along The Philosopher’s Path. The repetitions reinforce the rules and strengthen the order, and the recurring motives cushion the blows of initial surprise.

Let us now look at the learned ignorant in their creative role. A tightrope walker in mid-air over two skyscrapers has replaced the philosopher musing on the path of cherry trees. Our funambulist has the intellectual stance of Philippe Petit, an inimitable high-wire artist who, in his own words, has ‘learned to welcome life’s surprise, cheating the impossible, disregarding the rules, and learning to un...