eBook - ePub

Washington 101

An Introduction to the Nation's Capital

M. Green, J. Yarwood, L. Daughtery, M. Mazzenga

This is a test

Share book

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Washington 101

An Introduction to the Nation's Capital

M. Green, J. Yarwood, L. Daughtery, M. Mazzenga

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Washington 101 offers a layman's introduction to the richness and diversity of the nation's capital. An exploration of the history, politics, architecture, and people of the city and region, Washington 101 is a must-read for anyone curious to learn more about Washington.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Washington 101 an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Washington 101 by M. Green, J. Yarwood, L. Daughtery, M. Mazzenga in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Tecnología e ingeniería & Gestión medioambiental. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Subtopic

Gestión medioambientalPart I

Washington as Symbolic City

Introduction to Part I

Washington, D.C., is as much a symbol as it is a real city. Much of that symbolism derives from its status as a capital: even its very name is used as shorthand to describe the U.S. government (and how Americans view their government—usually negatively). But it is also a symbol for other reasons, including its distinctive appearance and its public places and spaces.

In the next three chapters, we consider Washington, D.C., as a symbolic city. We look first to the city’s architecture, especially its neoclassical public buildings and its highly geometric baroque street design. Both styles lend themselves to various interpretations of their “true” meaning, especially because together they give Washington an appearance unique among American cities. But in fact, what people think they stand for—democracy, power, religious (or religious-like) faith—were far from the minds of those who first brought those styles to the capital.

In chapter 2 we examine the preponderance of monuments and memorials in Washington. Taken collectively, they suggest that the city represents the nation at large and that it serves as a place of national remembrance. Yet there is considerable diversity in the style and structure of the city’s memorials, due not only to changing architectural tastes but to significant shifts in who Americans believe should be remembered and how. Even the same memorial can come to symbolize different values over time.

Chapter 3 explores another feature of Washington that distinguishes it from most other American cities: the presence of many, often world-class, museums. Like its monuments and memorials, Washington’s museums encourage a perception of the city as a national urban place in which America’s historic and cultural treasures are kept and displayed with pride. As we shall see, the multifaceted task of the city’s museums—to remember, to educate, to attract visitors, to preserve national identity—has sometimes led to controversy and conflict.

Chapter 1

Rome on the Potomac: The Classical Architecture of Washington

First impressions of a city are shaped by architecture, and Washington, D.C., evokes a powerful impression indeed. The city’s tallest structure is the Washington Monument, an Egyptian-style obelisk that looms far above all else. Bold columns and grand archways decorate white stone buildings throughout the capital. The city’s grid street pattern is overlaid with diagonal avenues and traffic circles, which, while at times confusing to navigate, direct the viewer’s eyes to many impressive buildings. It is no wonder that the city has been called “Rome on the Potomac.”

Washington actually features a diversity of building styles, and not all of its streets are broad, straight avenues.1 But two architectural features in particular distinguish the city’s central core2 from the urban centers of other American cities. First, the layout of central Washington is baroque: broad, diagonal avenues cut across a traditional street grid, with important structures, monuments, and squares located where multiple streets intersect (see textbox 1). Second, its public buildings, particularly those located on or near the National Mall, are mostly neoclassical in design, featuring columns, white or grey stone surfaces, and other elements from the great buildings of Ancient Greece and Rome (see textbox 2).

TEXTBOX 1: Features of the Baroque City Plan

The architectural scholar Spiro Kostof neatly summarized how Washington exemplifies several principles of Baroque planning, including the following:

1. a total, grand, spacious urban ensemble pinned on focal points distributed throughout the city

2. these focal points suitably plotted in relation to the drama of the topography, and linked with each other by swift, sweeping lines of communication

3. a concern with the landscaping of the major streets . . .

4. the creation of vistas

5. public spaces as setting for monuments

6. dramatic effects, as with waterfalls and the like

7. all of this superimposed on a closer-grained fabric for daily, local life.3

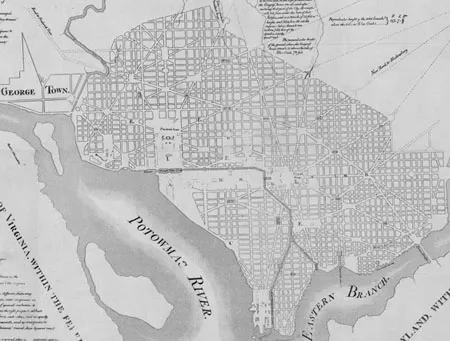

Some of these features, particularly the broad streets and creation of focal points, can be seen in L’Enfant’s original map (see figure 1.1).

TEXTBOX 2: Features of Neoclassical Architecture

As its name suggests, Neoclassicism, also sometimes called Classic Revival, is a style modeled after the great buildings of Ancient Athens and Rome. There are, in fact, many specific styles that are called “neoclassical,”4 but they all tend to share several features.

- Overall, neoclassical buildings are usually laid out symmetrically along one, and occasionally two, axes. They also make use of careful proportions in the relationships between height, depth, length, and other features.

- Neoclassical buildings often feature uniform stone surfaces, usually white or grey, in imitation of the appearance of contemporary ruins from the ancient world.

- “The heart of all classical architecture,” writes the scholar Robert Adam, is the use of columns of one or more major “orders.” The easiest way to distinguish the orders is by the capital (top) of the column; they range from the unadorned Doric to the curled Ionic and the highly ornate Corinthian. Other orders include the Tuscan and Composite.

- Arches and domes often appear in neoclassical buildings as well, particularly those seeking to replicate the style of Roman architecture.5

To many visitors, Washington’s Old World look symbolizes power, fitting for a city founded as a political capital. In fact, both neoclassicism and the baroque style were primarily introduced for other reasons, not least for their intrinsic elegance and beauty and their popularity at the time the city was established. One of the great strengths of both architectural styles, however, is their symbolic flexibility, which allows successive generations to find new meanings—such as political authority—in Washington’s physical appearance. That flexibility, along with political and artistic leadership by individuals and institutions at key moments in the city’s history, encouraged others to adopt or maintain neoclassicism and a baroque layout as the capital grew.

In this chapter we discuss the introduction of both styles to Washington, due largely to the leadership and vision of two individuals: Pierre L’Enfant and Thomas Jefferson. We then explore the varying associations that people have with neoclassicism and baroque architecture, illustrating how those styles can take on multiple symbolic meanings. Finally, we briefly review the waxing and waning of public support for the baroque and neoclassical styles throughout the city’s history, with particular attention to how the influential McMillan Plan of 1901 reinforced both at a critical historical moment.

The Creation of a Planned City

All cities are, to some extent, the result of human design and intent. But certain ones are the clear consequence of abstract maps imposed on a geographical space. Some plans impose order on existing disorder, as, for example, those of the nineteenth-century French planner Baron Haussmann, who replaced curving streets in Paris with straight roads and boulevards. Others create order afresh: Roman and other ancient civilizations laid out new cities in grids, for instance, as did settlers of early American towns.6

The city of Washington was planned because it was new, but creating a capital from scratch was not foreordained. Several existing towns and cities were contemplated as the seat of the federal government.7 However, George Washington was one of many former colonists who was suspicious of placing the capital in an existing urban place; as he put it, “The tumultuous populace of large cities are ever to be dreaded.” In 1783, a near rebellion of disgruntled former soldiers in Philadelphia, Congress’s temporary meeting place and a leading contender for the country’s capital, did little to counter this sentiment.8

Residents of Southern states wanted a more southerly location for the capital, so that “southern views on any issue—including slavery—would be more readily heard than northern ones.” They won, and, in 1790, after years of debate, Congress authorized a square, ten-by-ten mile territory of fixed boundaries to be created on the Potomac River. The territory’s exact location, determined by George Washington himself, had political, economic, and military advantages. It was midway between the North and South, along an important highway connecting both regions, bisected by a potential commercial waterway with two important riverside towns (Georgetown and Alexandria), and far enough from the ocean to be deemed safe from naval attack.9

For the city’s designer, Washington selected Pierre L’Enfant, a former Revolutionary Army soldier and practiced architect. It was a fateful choice. A man of “grand visions,” L’Enfant described the ubiquitous grid pattern of the typical city as “tiresome and insipid” and believed the new country deserved something more creative. His proposed city encompassed over 5,000 acres, as much territory as was then covered by Philadelphia, New York, and Boston put together. It embodied numerous features of baroque city design, including broad and straight streets, major squares and plazas, and avenues that connect important monuments or buildings (see figure 1.1). The intended effect was to join multiple distant points together and create impressive views of particular objects or scenes. Though L’Enfant insisted his plan was, as he put it, “wholly new,” it had some obvious parallels with, and may have borrowed from, several European cities (both actual and proposed) and settlements in North America.10

Figure 1.1 L’Enfant’s Original Plan of Washington

Source: Geography and Map Division, Library of Congress

The plan featured two main axes. A primary axis ran from Capitol Hill to a point just south of the president’s residence, close to where the Washington Monument stands today, and a promenade (now the National Mall) followed this line. The second axis was a major avenue connecting the Capitol to the home of the president (today’s Pennsylvania Avenue). The result would be a “sense of order in, and of tactile command over, a large organism of space and solid,” and by overlaying diagonal avenues on a traditional Cartesian grid, distant places would be joined to create what L’Enfant called “a reciprocity of sight.”11

Explaining L’Enfant’s Map

Why did L’Enfant design the city as he did? In the late eighteenth century the baroque style had become quite fashionable in Europe, but L’Enfant was driven by more than artistic trends. For one thing, he believed that a city should be harmonious with existing topography. He rejected a basic street grid for failing to take advantage of the area’s hills, ridges, and waterways, and he dedicated its higher points to important government buildings like the Capitol. Certain city streets, such as Twelfth Street southwest and...