eBook - ePub

Experimental Economics

Volume II: Economic Applications

Pablo Branas-Garza, Antonio Cabrales, Pablo Branas-Garza, Antonio Cabrales

This is a test

Share book

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Experimental Economics

Volume II: Economic Applications

Pablo Branas-Garza, Antonio Cabrales, Pablo Branas-Garza, Antonio Cabrales

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

How do applications affect behavior? Experimental Economics Volume II seeks to answer these questions by examining the auction mechanism, imperfect competition and incentives to understand financial crises, political preferences and elections, and more.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Experimental Economics an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Experimental Economics by Pablo Branas-Garza, Antonio Cabrales, Pablo Branas-Garza, Antonio Cabrales in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Organisational Behaviour. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Market Organization and Competitive Equilibrium

Antoni Bosch-Domènech and Joaquim Silvestre

Introduction

The market (or better, markets) is any system that facilitates exchange. It is therefore a necessary condition for economic activity, as well as the subject matter of economic science. The theoretical analysis of markets, pioneered by classical economists (Walras, 1874, Edgeworth, 1881) and continued by Marshall (1890), culminates in the precise model of perfect competition (Arrow and Debreu, 1954). The competitive model postulates that participants in the market decide the quantities that they wish to buy or sell according to the market price, which each participant takes as given. A price is an equilibrium price if the buying and selling plans of the various participants are compatible.

The competitive model is static: it determines the equilibrium price and quantity, but it does not specify how to reach them. In a way, it disregards (ephemeral) disequilibrium situations. When forced to provide some justification for the dynamic path to equilibrium, Walras appeals to the metaphor (understood as such by both Walras and his successors) of a virtual auctioneer, who adjusts prices according to the difference between supply and demand, and does not allow trade to occur until the equilibrium between supply and demand is attained. But in fact the competitive equilibrium model is silent on the manner in which transactions are performed and how equilibrium is arrived at.

Wanna trade?

The experimental study of competitive markets begins with Edward Chamberlin (1948) and matures with the experiments of Vernon Smith (1962, 1964). Both attempt to test the competitive model in an isolated market (i.e., to test whether the theoretical values of the competitive equilibrium model are good predictors of the magnitudes reached by prices and quantities in the experiment) as well as to check whether, as implied by the competitive model, the experimental market outcome maximizes the sum of the profits for buyers and sellers, in which case we say that we have reached 100% efficiency. Yet market experiments allow us to observe the buying and selling decisions made by the experimental participants (or “subjects”) in real time: as a result, we are induced to focus on the dynamics by which individual decisions drive economic variables, sometimes towards equilibrium and at other times away from it.

In order to construct an environment, no matter how simple, in which to explore the behavior of a market, one must establish the rules by which the market should operate (i.e., the norms that regulate how participants can bargain, how agreement is reached, or how to ensure that agreements are implemented). No market can exist without operating rules, be they simple or complex, explicit or implicit, because a market is essentially the set of its operating rules. For this reason, when an economist refers to a market she means the rules and institutions that define it, rather than the physical location where trade occurs (say, the village market place, or the central market in Southampton).

Two important features differentiate the experimental market rules of Chamberlin from those of Vernon Smith. First, in Chamberlin’s experiment participants move about a room and try to reach a buy–sell agreement with another participant. As in more primitive markets, sellers and buyers are scattered in space and time, and this entails a transaction cost because they have to find each other and negotiate one on one. Vernon Smith (1962) replaces the rule of one-on-one bargaining with a more modern institution: he creates an environment where buyers and sellers meet by rules that publicly disclose their offers to buy or sell in real time, as well as the prices of the trades already contracted. More specifically, it is a form of auction, called a double auction, where buyers increase their buying (bid) prices and sellers decrease their selling (ask) prices until some bid price coincides with an ask price and a deal is closed. Hence, the main difference between Chamberlin’s and Vernon Smith’s markets is that participants in the former have to search for trading partners and bilaterally negotiate, whereas in the latter negotiation is multilateral: everybody is aware of what everybody else is doing. The information on the various bids and asks, as well as on the prices of the transactions reached, becomes a public good: both buyers and sellers may use the information at zero cost.

The second difference is that, whereas Chamberlin ends the experiment once all possible transactions have occurred, Vernon Smith repeats the experiments several times, keeping the same parameters, but without carrying over the outcomes of any one round. Each round is independent of the other rounds: the experiment starts each time at zero, but of course the participants acquire experience that will no doubt influence their decisions in the following rounds. What is the motivation for repeating the experiment?1 Vernon Smith explains that, if we want to test whether the market converges to the theoretical competitive equilibrium, we must allow participants in the experiment to acquire experience and modify their behavior in light of previous experience, as happens in real-life markets. Rather than trying to confirm that prices coincide with competitive equilibrium prices from the first transaction, the aim is to check whether there is a trend of convergence towards the equilibrium, and, if so, what is the speed of convergence.

But the preferences of the participants are similarly “induced” in either experiment: each buyer and each seller is told her (or his) reservation price for buying or selling one indivisible unit of the (fictitious) good traded in the experimental market.2 When we, the experimenters, fix the reservation price of each participant (i.e., for a buyer, the maximum price at which she will be willing to buy and, in the case of a seller, the minimum price at which she will be willing to sell), we induce in each participant “her” preferences which, obviously, may well vary from person to person.3,4 To summarize, the reservation price is private information for each participant: only she (and of course, the experimenter) knows it.

Note that, because the experimenter knows all reservation prices (she has provided them), in order to construct the demand curve for this market, all she has to do is to aggregate the buyers’ reservation prices. Similarly, by aggregating the sellers’ reservation prices she will obtain the supply curve.5 Once she has determined the supply and demand curves, it is trivial to find the competitive equilibrium price and quantity from the point of intersection of the curves. Next, after knowing the equilibrium values, she can compare the theoretical values with the prices and quantities observed throughout the experiment and, using this comparison, she can ascertain the extent to which the equilibrium of the competitive model provides a good approximation to the experimental results observed. This last sentence should be emphasized because it encapsulates the capacity of an experiment to act as a method to test, or check, a theory: the idea is to create an environment in which the predictions of the theoretical model are precise, so that one can experimentally verify the extent to which they are fulfilled.

Finally, we should note that the incentives of the participants in either experiment were similar. In each period, sellers could sell a maximum amount of the “good,” and buyers could only buy a given quantity of the “good.”6 A buyer’s earnings were higher the greater the difference between her reservation price and the price paid for the purchase, and a seller’s earnings were higher the greater the difference between the price received in the sale and her reservation price.

Why, at the risk of being tedious, do we go to such lengths to explain the details of the rules imposed on their markets by Chamberlin and Vernon Smith? First, because their designs have been copied by many subsequent experiments.7 Second, because, as we discuss below, we face a crucial issue in experimental methodology. Chamberlin observed that the predictions of the model were not realized, and interpreted his results as supporting the hypothesis that what happens in real markets differs from the predictions of the theoretical competitive model. Vernon Smith, on the contrary, observed a very clear tendency to converge towards the predictions of the competitive model, and, moreover, that the convergence was fast. In addition, the experimental markets approached the 100% efficiency predicted by the competitive model. Leaving aside for the moment a detailed analysis of these results, we must make a key methodological remark. We have seen how a change in the design of the experiment, which at first blush may not seem essential, may drastically alter the outcome of an experiment. Moving from individual bargaining to a market organized by a double auction allows us to validate a hypothesis that had been disproved with the first design. The reader should draw an important lesson from this: details are very important in the design of an experiment. Sometimes a small alteration can substantially modify the results of an experiment. Thus, one may ask, how can you trust an experimental result? The answer is obvious but important. One must repeat and replicate the experiment in order to test its robustness to variations.

Makin’ magic

The miracle

Let us now pay attention to the results of the experiments described. Few people are surprised when the predictions of a theoretical model are not fulfilled in reality; perhaps because of this, Chamberlin’s experiment went relatively unnoticed.8 Yet it is nothing short of extraordinary that the competitive model, which hypothesizes a price known to all market participants but not manipulated by any of them, can be an excellent predictor of what happens in an experimental market, where these and other assumptions (presented in detail below) are not met.

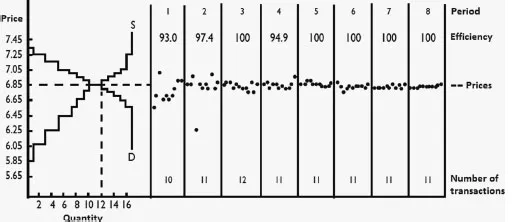

But is the competitive model such a good predictor of Vernon Smith’s experiments? Consider Figure 1.1, which is representative of thousands of similar experiments conducted over the years. On the left are the curves of supply and demand that the experimenter knows (but as will be recalled, are not known by the participants in the experiment) and allow the experimenter to compute the price and the equilibrium quantity. On the right, represented by dots, we have the prices at which each transaction has been carried out in each of the periods of the experiment: eight in this case, numbered from one to eight; the vertical lines are used to separate periods. For each period, under the period number, we read the percentage of market efficiency in the period (93.0, 97.4 . . .) and, at the bottom, another number indicates the number of transactions that have occurred in the period (10, 11, 12, 11, . . .). What do we see in the graph? At least three things: a rapid convergence of prices towards the equilibrium price (6.85) and of efficiency towards 100%, as well as transaction volumes that stabilize in the middle of the three equilibrium quantities – 10, 11 and 12.

Figure 1.1 Vernon Smith (1962)

Note: Equilibrium price and quantity. Experimental prices and quantities across the eight periods of the experiment.

We do not know what your reaction was when you first encountered this result. As noted, the competitive model is based on extreme assumptions. In detail:

(a) Buyers and sellers take the price as given.

(b) The above assumption is justified by the idea that buyers and sellers are so numerous, and each of them is so unimportant that none of them in isolation can have an effect on prices: for example, both Cournot (1838) and Edgeworth (1881) justify the above assumption as a limit when the number of participants tends to infinity and the weight of each of them in the economy becomes negligible.9

(c) Participants know the market price.

(d) Knowing the price, agents make decisions on how much they want to buy or sell in order to maximize their own profit or utility.

Well, perhaps in the experiment participants did make maximizing decisions (although we cannot be sure of that). Yet we certainly can be sure that buyers and sellers in the experiment in no way felt that the price was fixed, and not only did their best to manipulate the buying and selling prices, but actually managed to do this. Nevertheless, the predictions of the model are fulfilled. Furthermore, the experimental results were obtained without the participants needing to know the “market price:” they just needed their private information and the information acquired by observing the various bids and offers, as well as the actual prices of a few transactions in a few repetitions. (This is particularly the case in Figure 1.1’s experiment, where 100% efficiency is reached and maintained after five repetitions. After that, prices just fluctuate around the equilibrium value and the quantities exchanged are the equilibrium ones from the beginning.) Finally, the convergence of the prices and quantities to the competitive equilibrium is achieved with only four or five buyers and four or five sellers: far from the infinite numbers proposed by Cournot and Edgeworth.

Although we do not know what your reaction was, we do know Vernon Smith’s reaction because he put it in writing: “I am still recovering from the shock of the experimental results. The outcome was unbelievably consistent with competitive price theor...