A Global Doll’ s House aims to answer a very simple question: what accounts for the global success of Henrik Ibsen’s most popular play? We consider the question from two angles: cultural transmission and adaptation. By tracing the cultural transmission of the play through its global performances, we uncover the social, economic, and political forces that have secured it a place in the canon of world drama; by looking at multiple adaptations we reveal how artists have been able to re-create the play successfully in so many cultural contexts.

When Ibsen wrote the play that he named

Et dukkehjem, he was hardly known outside Scandinavia and Germany, and it became his passport to international fame. Its protagonist, Nora Helmer, rivals Antigone, Carmen, Medea, and Juliet as the most performed, discussed, and debated female character on the international stage. The play premiered in Copenhagen in 1879.

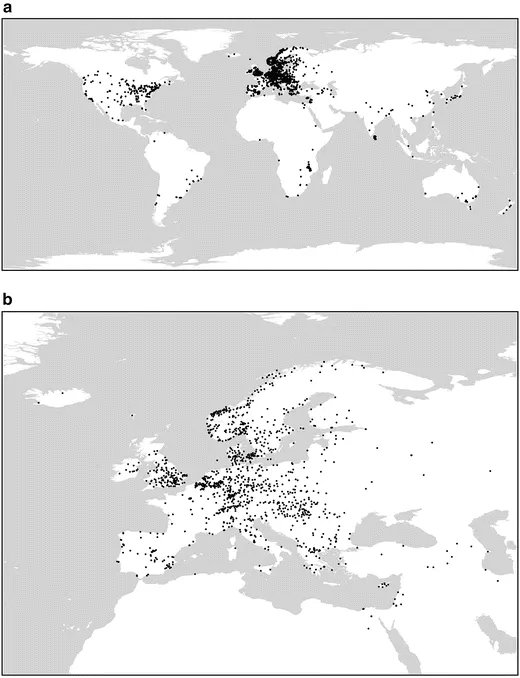

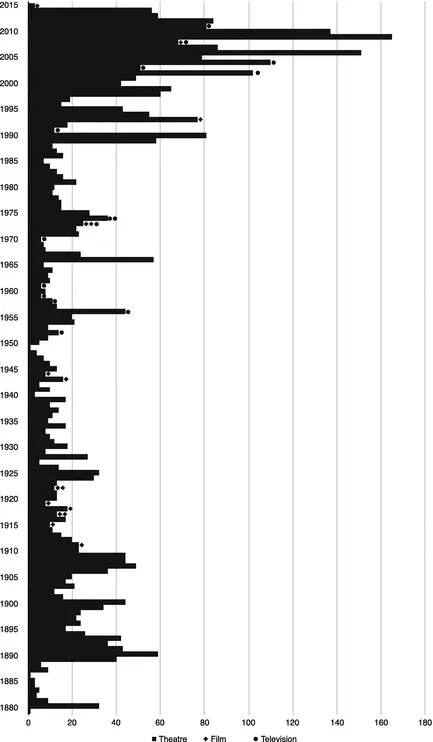

1 It has since been performed in thirty-five languages in eighty-seven countries, thirty-nine of which are outside Europe; with 3787 records of productions it has become one of the world’s most produced dramas (see Figs.

1.1 and

1.2). It has been adapted into eight silent films and seven feature films; been televised at least twenty-five times and had numerous radio broadcasts; and more recently, a plethora of extracts have appeared on YouTube. The play is known by multiple titles, the most familiar in English being the mistranslation

A Doll’ s House (Sandberg 2015, 72). In 1880, Ibsen wrote to his Swedish translator, Erik af Edholm, ‘[i]t is quite rightly the case, as you assume, that my play’s title,

Et dukkehjem [dukkehjem = dollhome] is a new phrase, which I myself have made up, and I am very pleased that they will repeat the phrase in Swedish in a direct translation’ (Ibsen 1880b, 11–12).

2 Rather than

A Doll Home, the title given to the play by William Archer was

A Doll’ s House, which has become the standard title used in English bibliographies and digital archives, and we follow this convention in the title of this book.

3 But within this study we use the original Dano-Norwegian title,

Et dukkehjem, to refer both to the play-script and the entire ‘work’: this is the play in all its versions, translations, and adaptations, and all the productions presented live on stage or recorded for transmission by film, radio, television, Internet, and so on. This all-encompassing ‘work’ is our focus, as we aim to avoid what Pierre Bourdieu has called the ‘ideology of the inexhaustible work of art’, and instead take as our point of departure ‘the fact that the work of art is in fact made not twice, but hundreds of times, thousands of times, by all those who have an interest in it’ (1993, 111). When we refer to individual productions we use their advertised titles if they conform to the Roman alphabet and translate them into English as

A Doll Home when the original is in a different script.

As

Et dukkehjem appears on school and university curricula worldwide, we assume that most of our readers will have encountered it on stage, on film, or in the classroom. To renew this acquaintance, we begin with Ibsen’s ‘Notes for a Modern Tragedy’, written a month after he moved to Rome and began working on the play in September 1878

4 :

There are two kinds of spiritual law, two kinds of conscience, one in man and another, altogether different, in woman. They do not understand each other; but in practical life the woman is judged by man’s law, as though she were not a woman but a man.

The wife in the play ends by having no idea of what is right or wrong; natural feeling on the one hand and belief in authority on the other have altogether bewildered her.

A woman cannot be herself in the society of the present day, which is an exclusively masculine society, with laws framed by men and with a judicial system that judges feminine conduct from a masculine point of view.

She has committed forgery, [and it is her pride]; for she did it out of love for her husband, to save his life. But this husband with his commonplace principles of honour is on the side of the law and regards the question with masculine eyes.

Spiritual conflicts. Oppressed and bewildered by the belief in authority, she loses faith in her moral right and ability to bring up her children. Bitterness. A mother in modern society, like certain insects who go away and die when she has done her duty in the propagation of the race. Love of life, of home, of husband and children and family. Here and there a womanly shaking-off of her thoughts. Sudden return of anxiety and terror. She must bear it all alone. The catastrophe approaches, inexorably, inevitably. Despair, conflict and destruction. (Krogstad has acted dishonourably and thereby become well-to-do; now his prosperity does not help him, he cannot recover his honour.) (Ibsen ([1878b] 1917, 91) 5

A year later when he delivered the manuscript of

Et dukkehjem to his publisher, Frederik Hegel, he wrote, ‘I cannot remember that any of my books have given me greater satisfaction in the development of the details than this particular one’ (Ibsen 1879b, 505–06). These meticulously crafted details were cemented into a plot line that manipulated familiar nineteenth-century tropes of illness, financial corruption, blackmail, and sexual desire. It was not until the second half of the play that Ibsen confounded the narrative expectations of his audience. The shift from the predictable to the unpredictable is evident in the final two sentences of our summary of the

Et dukkehjem plot:

Nora, a happily married woman with three small children, has a closely guarded secret. Early in her marriage, her husband developed a serious illness; his recovery was dependent on leaving the cold climate of the North. Nora forged her dying father’s signature to secure a loan to finance this journey. Eight years have passed and she is still secretly paying off the loan. Torvald, her husband, has just been appointed as the manager of a bank and the family’s finances are changing; it is Christmas and there is plenty to celebrate. Nora has never told Torvald about the loan. It is only when Krogstad, the loan shark, tries to blackmail her, that she realises her forgery was a criminal act. She suddenly understands the enormity of her crime and begins to believe that she is morally corrupt and unfit to raise her children. Krogstad now works at the bank, but with his history of financial indiscretions, he fears that he will lose his position. He tells Nora to persuade Torvald to secure his future employment, but she fails and Krogstad is sacked. Nora decides to seek help from Dr Rank, a close family friend, but she changes her mind when he confides his love for her and reveals that he is suffering from a terminal disease. The blackmail plot escalates when Krogstad writes a threatening letter to Torvald. While this letter sits in a letterbox, waiting to be opened, Nora asks Mrs Linde, her old school friend, for help. Mrs Linde agrees to use her influence over Krogstad to thwart the blackmail plot, but she insists that Torvald is told the truth. Nora is terrified that Torvald will sacrifice himself rather than see her prosecuted for a criminal act, but when he reads Krogstad’s letter, he capitulates to its demands, and blames Nora for ruining his life. Nora is deeply shocked to discover Torvald’s true nature. Through Mrs Linde’s intervention, the blackmail threat is removed, but Nora realises that her childlike dependency and ignorance of the world have made her incapable of raising her children. She decides to leave her husband and her children, educate herself, and strive to live as a self-determining human being.

The International Ibsen Bibliography lists 3540 items with material on Et dukkehjem that are attributed to 2085 authors; they include 1076 books, and 2392 journal and newspaper articles (Nasjonalbiblioteket 2012). Readers could be forgiven for assuming that there is nothing more worth saying about this theatrical phenomenon, but the underlying premise of our book is that new ways of looking produce new ways of thinking. IbsenStage, the database that holds over 15,000 production records of Ibsen’s plays, has made these new ways of looking possible.

The ‘distant reading’ developed by literary historian Franco Moretti is central to our approach: he notes that ‘distance is however not an obstacle, but a specific form of knowledge: fewer elements, hence a sharper sense of their overall interconnection. Shapes, relations, structures. Forms. Models’ (2005, 1). Looking from a distance at the 3787 records of Et dukkehjem productions in the IbsenStage database, we see patterns in the data that guide us towards new sites of enquiry. When we reach these sites, we zoom in to look at the work and lives of particular artists, commercial and government funding, specific performances, genres of adaptation, and multiple versions of a single scene to find the evidence that can help explain the global success of the play. No single performance is examined at great length, but full details of all the productions mentioned are held in IbsenStage. Before describing the database and the methodology we use to analyse patterns in its records, we first locate our study within the wider frameworks of digital humanities and contemporary Ibsen scholarship.

Digital Humanities

Digital humanities opens up new avenues for theatre scholarship. Sarah Bay-Cheng proposes that theatre historiography must take account of the digital; she advocates that theatre historians embrace ‘the digital records of past performances and the digital circulation of images in the present’ (2010, 133). This book takes up her challenge in applying a digital approach to interrogating the production history of one of the most popular plays in the global repertoire. We use techniques of data analysis, quantification,and visualisation in an attempt to understand the dynamic forces that have shaped, and continue to shape, the production of world drama.

Audiences for performance are now accustomed to the use of computer technologies in the theatre. Computers are used to control light, sound, and the projection of text and images in performance, and companies use digital media to transmit images and video of live productions to audiences around the world. The use of computers in theatre research has also become widespread. Databases assist in analysing information about performance events and artefacts; sound, image, and video are incorporated into digital multimedia to represent the production history of a play or new genres of performance; and three-dimensional theatre models provide virtual venues for re-creating performance from the past or simulating future prospects for production (Herbert 1986; Donohue 1989; Saltz 2004). Theatre scholars have become optimistic about the new kinds of teaching, research, and performance that digital technologies enable as the convergence of digital archives, broadband media, and Internet services provide distributed access to performance, and previously dispersed materials become increasingly accessible (Carson 2005; Causey 2006; Dixon 2007).

Across the arts and humanities, researchers have taken up the potential that computers provide, borrowing methodologies from the sciences, where data have been analysed using digital ...