We ought not to look back, unless it is to derive useful lessons from past errors, and for the purpose of profiting by dear bought experience. To enveigh against things that are past and irremediable, is unpleasing; but to steer clear of the shelves and rocks we have struck upon is the part of wisdom…

George Washington to John Armstrong, March 26, 1781 1

Over two hundred years ago, as British–American colonial relations began to deteriorate, colonial leaders recognized the importance of informing and connecting with the public, both domestically and overseas. 2 Only a month after convening as a congress to represent the colonies of then British America, the representatives of the First Continental Congress deemed addressing the British public a prudent initial step toward resolving the ever-widening breach between the colonies and the British government. The gathered congress “resolved, unanimously” on October 11, 1774, to compose an address to the people of Britain , to explain the British–American colonists’ view of Parliament’s actions toward the colonies. 3 More open letters would be written to the people of Quebec and Jamaica in order to explain the colonies’ reasons for opposing England ’s legal measures against the colonies.

Today, US leaders still note the importance of engaging with people abroad, evidenced not only by The 9/11 Commission Report, but also subsequent reports and public statements made by political and military leaders. 4 More recently, comments by US leaders advocate bolstering public diplomacy to counter the effects of terrorist propaganda and Russian propaganda . 5 Despite continued interest and repeated calls to strengthen US public diplomacy, more than a decade after 9/11, America’s national communication efforts with foreign publics are inadequate; the “…public information campaign is a confused mess,” 6 despite considerable reforms since 2013. 7 When the nation was most vulnerable immediately following the 9/11 attacks and when America most needed to engage with publics abroad, the country was unable and remains unable to use public diplomacy effectively in US statecraft . Since the onset of the Cold War, “…the American people and their government struggled to define the appropriate role for overseas information. There has always been a broad consensus on the need to more effectively communicate U.S. messages and values. However, when it came to the specific nature of such communication, opinions diverged.” 8

For over a decade, American political leaders, public diplomacy practitioners, and academics have raised the issue of how America practices and incorporates public diplomacy in its statecraft, especially in the last three years. 9 Much of the debate focuses on the issues which continue to inhibit effective practice and bureaucratic questions as to public diplomacy’s place in American statecraft, as well as defining the concept.

So why look back at the past when the problems facing US public diplomacy are in the present? As George Washington observes, looking at the past affords the opportunity to see where the “shelves and rocks” are so that they may be avoided. This is the intent of this book, to look back in order to learn from past experiences of US public diplomacy. More than this, this book seeks to provide context for today’s problems facing US public diplomacy. As the following chapters will demonstrate, some of the problems plaguing US public diplomacy are deeply embedded in past experience, US political culture, foreign policy traditions, and ideas about how the US should engage the world. Unfortunately, the US cannot escape its past, and the nation is unlikely to surmount obstacles tied to national identity, traditions, and experience which inhibit the strategic integration of public diplomacy in US statecraft. Then, why bother at all with examining over 170 years of US history to “fix” public diplomacy if it cannot be fixed? The reason is just as Washington said: to know where hazards are so that we may avoid them as much as possible. This manuscript will draw upon the history of US public diplomacy in order to suggest ways to navigate the problems currently impeding US public diplomacy, to provide context.

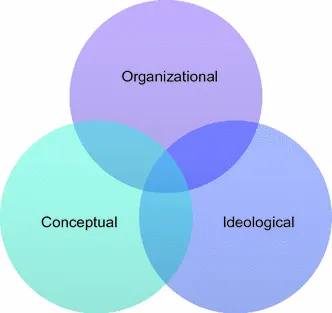

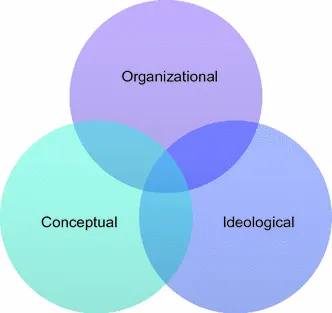

Before delving into early examples of US public diplomacy, the proceeding pages identify three general categories of problems facing US public diplomacy based on assessments and observations made by former practitioners, policymakers, scholars, Congressional reports and testimony, Inspector General and Government Accountability reports, and assessments of the US Public Diplomacy Advisory Commission. These problem categories provide a framework for observing connections between public diplomacy of the past and the present, demonstrating how these issues are tied to the nation’s past experience, traditions, and political culture, as will become apparent in the proceeding chapters. As the cases of early US public diplomacy will show, some factors such as national experience, tradition, and national political culture act as catalysts, stimulating and shaping US public diplomacy as we know it today. On the other hand, those same forces also act as inhibitors of public diplomacy, contributing to the problems seen today. The proceeding pages identify and describe the three broad problems of public diplomacy based on scholars’ and practitioners’ assessments and government reports: conceptual, organizational, and ideological. In examining each problem category, connections will be made between how the issue effects public diplomacy and the historical roots of the problem. The final section of this chapter will outline how each historical case was selected and evaluated.

Problems of Public Diplomacy

In the last thirty years, public diplomacy has become the subject of inquiry among academics, current and former practitioners, government research bodies, and independent think tanks. The ever-growing body of research on US public diplomacy acknowledges its importance and that its significance in international relations is increasing, rather than diminishing. 10 The body of research furthers understanding of public diplomacy either from a historical angle, a practical perspective, or by looking at the impact of public diplomacy. This study traces the origins of US public diplomacy to better understand the roots of the problems regularly cited by scholars, practitioners, and government audits, to provide context for practical ways to overcome these issues.

There is general agreement regarding the problems confronting US public diplomacy. These problems or impediments often highlighted by scholars and practitioners can be grouped into three categories: conceptual, organizational, and ideological (Fig.

1.1).

Organizational problems refer to issues related to the agencies’ or departments’ responsible for administering US public diplomacy as well as the role or non-role public diplomacy plays in policymaking or carrying out foreign policy. Conceptual problems are issues tied to what public diplomacy actually is, what public diplomacy is used for, and what it should or should not do. Ideological problems are derived from deep-rooted beliefs and interpretations about America’s relationship with the world, what is appropriate or not. Ideological issues are also connected to an ingrained view that American values and principles are universally acceptable. Many of these issues plague other elements of US statecraft (diplomacy, intelligence, defense), but for US public diplomacy, each of these areas can be connected to all of the often cited problems confronting US public diplomacy both in the past and in the present. 11 The case studies featured in this book demonstrate how these problems manifest themselves in early US public diplomacy and often become recurring issues.

Whether looking at scholarly, practitioner, or government literature regarding the practice and use of public diplomacy; the problems cited fall into these three categories. For example, Nancy Snow and Philip Taylor noted that while “scores of reports and white papers” are produced on the need for reform and new public diplomacy initiatives, there is little done to clarify and solidify the conceptual understanding of public diplomacy itself. 12 Cull’s comprehensive historical work on the United States Information Agency (USIA) from 1945 through its eventual dissolution recounts the repetitive structural and organizational problems which plagued the institution. 13 Many of these same issues are noted by Richard Arndt, Wilson Dizard, and Hans Tuch: the disconnect between public diplomacy and policymaking; overlap between USIA and other government agencies’ work; and problems clearly defining USIA’s mission, to name a few. Even after the USIA ’s absorption into the Department of State in 1999, structural and organizational problems continue to undermine the practice of public diplomacy. 14 US political ideology is not often cited as a specific issue confronting American public diplomacy, but some scholars and practitioners have made passing references to this issue. 15 For example, Hans Tuch refers to an observation made by a public diplomat and how Americans assume the world is sympathetic to American ideas and by extension the nation’s policies. 16 The cases featured in the proceeding chapters...