Act I

Chekhov gives us clues, in the stage direction, to what may happen. The room is “still called the nursery” (Orchard, p. 1298). This may relate to something in the past, to something that has changed, but has yet to be recognized as changed. If it’s something that has yet to be recognized as changed, what, then, might that say about those people who refuse to recognize it? Chekhov additionally sets the scene by establishing the time. It’s nearly 2 a.m. and one knows the train is two hours late. Lopakhin, a merchant, is there to pick them up, but has fallen asleep. One inference that can be made is that he’s tired, but the other may be that he isn’t very interested in seeing whoever is coming. It might also allude to notions of “control” since control issues are important. One understands that it is Mme. Ranevskaya and her family who are coming and Lopakhin talks about her nostalgically but with a tinge of bitterness.

One learns that his roots are peasant roots. His father abused him, but that would have been expected, but it’s not the abuse that is an issue here. The issue is not one of correct political behavior but one of social status. The reader is aware that Lopakhin comes from peasant stock and that might be a key issue here. When Mme. Ranevskaya washed him off after he was hit in the face by his father, she said, “Don’t cry little peasant it’ll heal in time for your wedding” (Orchard, p. 1298) the comments he makes reaffirm his roots, but they also accent class differences and class differences are at the fundamental core of the play. Lopahin even repeats the word “peasant” especially in relation to the white waistcoat and yellow shoes that accent who he was, but also what he has become.

So, the implication of a combination of who he is and who he has become in relation to Mme. Ranevskaya and her family will establish a clear point of conflict not only between Lopakhin and Mme. Ranevskaya, but also between Lopakhin and the family. At the same time, one reads of Dunyasha, the maid, trembling. Lopakhin says, “You’re too soft Dunyasha. You dress like a lady, and look at the way you do your hair. That’s not right. One should remember one’s place” (Orchard, p. 1299). The fact that it’s important to remember one’s station acts as a kind of refrain throughout the play, but it also establishes an anxiety on Dunyasha’s part that will be demonstrated later.

At that point, a new character, Yepihodov, a clerk, brings in flowers from the garden. Yepihodov’s boots are polished, but squeaky and because of that Yepihodov then asks Lopakhin what to use to remove the squeak. It is of interest that he asks Lopakhin for advice about squeaking shoes and no one else, presumably, because Lopakhin claims he is a peasant. But Lopakhin responds angrily to the question by stating: “Oh, get out! I’m fed up with you” (Orchard, p. 1299). One can only assume that Lopakhin is still caught between “knowing his place” and “not wanting to recognize his place.” Chekhov expands Yepihodov’s comedic character by first having Yepihodov talk of awful things happening then the things happen to him: “Every day I meet with misfortune. And I don’t complain. I’ve got used to it, I even smile” (Orchard, p. 1299). His apparent buffoonery is expanded throughout the play.

Lopakhin asks Dunyasha for glass of kvass, which is one of the national alcoholic drinks of Russia, and also popular in Eastern Europe. It’s made by a simultaneous acid and alcoholic fermentation of wheat, rye, barley, and buckwheat meal, or of rye bread, with the addition of sugar or fruit. In this case, the fruit is obviously cherry. And though it has been a universal drink in Russia since the sixteenth century it is primarily a peasant drink. These “details” augment Lopakhin’s character.

So, what reads so far is an excellent example of the use of economic language. In a drama there isn’t the luxury of using narration to carry the action forward; in drama there is only dialogue and gesture to rely on both of which Chekhov excels at presenting. As Dunyasha talks to Lopakhin, she establishes the relationship between herself and Yepihodov yet Lopakhin’s response is indifference, which clearly relates to, and reinforces, class issues.

Dunyasha’s talk about her interest in Yepihodov is cut short by the sound of horses outside as Lopakhin re-emphasizes the time lapse of five years. The re-mentioning of five years reinforces the notion of passing time and with the passing of time comes change. At the same time, Lopakhin is concerned about his “appearance,” which coincides with the constant undercurrent about his interest in Mme. Ranevskaya.

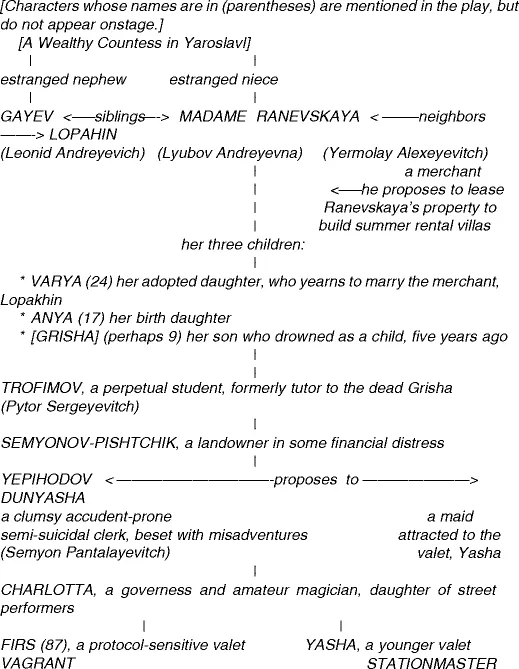

At this point, the rest of the ensemble arrives and in a particular order. Not unlike the characters in a Molière play, the main characters are presented in the following order:

Lopakhin

Dunyasha

Yepihodov

Lubov,

Anya, Charlotta, Varya, Gayev, Firs with

Mme. Ranevskaya and Gayev coming in led by Pishchik

First, Chekhov presents what could be considered the “marginal characters,” then, for the most part, “the aristocracy.” After they are presented, there is a series of interactions between the following characters:

Anya(Mme. Ranevskaya’s daughter)

Varya(Mme. Ranevskaya’s adopted daughter)

They begin with Anya’s line “Let’s go this way. Do you remember what room this is, Mamma?” (Orchard, p. 1300) and continues up to Lopakhin’s entrance (Orchard, p. 1301). Prior to Lopakhin’s entrance, there is a keen family interest in material objects, the comfort of material objects.

Some of the key issues that are established very early in the act are:

- 1.

An emphasis on things at the estate being the same as they were;

- 2.

The sale of the orchard appears as a prominent issue;

- 3.

The parallel monologues tend to reinforce separation between and among characters; and

- 4.

Indifference of former confidantes to something less than that station reinforces the fact that things are, in fact, not the same.

Each of these issues relates to one of the major components of the drama: conflict and, specifically, conflict related to change. At that point, Dunyasha informs Anya (a former confidante) about her engagement to Yepihodov; however, Anya’s initial response is “There you are, at it again…I’ve lost all my hairpins” (

Orchard, p. 1300). What continues is that they speak in

parallel monologues. Conventionally, speech in drama is a device for simultaneous two way communication: the characters talk directly with each other and at the same time they talk indirectly to the audience. But in Chekhov, these two functions of dialogue seem often separated. The characters seem to be talking to themselves in a daze primarily for the purpose of giving the audience direct exposition. (Deer 1958, p. 31)

This type of “audience directed” dialogue persists throughout the play either in the form of parallel monologue or a kind of absurdist dialogue.

While Dunyasha continues talking about Yepihodov, Anya is consumed by being back home. That relative indifference on Anya’s part not only establishes a class difference that was not apparent before she left, but it also establishes the fact that what they used to be they no longer are. Anya is now 17. Five years earlier they were both pre-teens, children; now, they are late teens and those intimate intrigues they shared are no longer important for Anya. The “trembling” that Dunyasha feels early in the act is related to her anxiety about seeing Anya again, which slowly gives way to an acceptance on her part that things will never be the same again. This is evinced by how Anya recounts the trip back to Russia, about living in Paris, and about specific things related to Mme. Ranevskaya’s character that will be critical to an understanding of the play. Anya not only talks about the kinds of people who visited them in Paris, but she alludes to the fact that all of Mme. Ranevskaya’s property is going to be sold.

In the middle of the dialogue, Varya says: “In August the estate will be put up for sale” (Orchard, p. 1301) prompting Anya to exclaim: “My God!” At that same instant, Lopakhin appears, bleats, then disappears. That appearance and disappearance is not serendipitous. Chekhov can’t waste words or gestures. The subtext is that there may be a connection between Lopakhin and the sale of the orchard. The fact Anya appeals to “divine intervention” coterminous with Lopakhin’s appearance is clear. Varya’s response to him: “What I couldn’t do to him!” followed by Anya’s statement: “Varya, has he proposed to you?” indicates that there is an obvious connection between them and while Varya continues to bear all to Anya in her confession about Lopakhin Anya changes the subject to the brooch that her mother bought her. Anya not only changes the subject, but also adds something about balloon rides. What that apparent indifference tends to do is further distance them from the relevant issues at hand (namely, the sale of the estate) and distance them from each other. In that sense there is a conflict between what is provincial and what is cosmopolitan.

At that point, there is the entrance of Yasha, the young valet. Clearly, he’s been affected by his time in Paris and by virtue of that experience anything that is unlike Paris suggests the provincial. His attitude clearly reflects that kind of affected behavior, especially in relation to Dunyasha with whom he had some interest in the past but to whom he affects ignorance now. With the acknowledgment of Trofimov, the tutor, one discovers from Anya that it’s been six years since her father’s death and many years since her brother’s; that acknowledgement introduces us to Trofimov.

There is also the re-introduction of Firs who their 87 year old manservant who still wears old-fashioned livery. In spite of age, senility, and infirmity, Firs is faithful; faithful both to the family, to the virtues the family has long held, and to the tradition of his station as reflected in his uniform, his demeanor, and his dialogue. His attitude is set in contrast to Yasha, which establishes differences in sensibility, but also reinforces Firs faithfulness to the family and to the traditions of the past.

Prior to this point, the dialogue has been focused on the rest of the family, but the dialogue finally shifts to both Gayev and Mme. Ranevskaya as they enter. As they walk into the room, they’re both talking about billiards. She says: “Let’s see, how does it go? Yellow ball in the corner! Bank shot in the side pocket!” as her brother replies: “I’ll tip it in the corner! There was a time, Sister, when you and I used to sleep in this very room and now I’m fifty-one, strange as it may seem” (Orchard, p. 1302). That exchange recalls the past, but also establishes the fact that they are of a different social class since peasants wouldn’t have been playing billiards and that he recalls those days with a bittersweet memory. It may “seem strange” since the comment is a denial of the present. It is not coincidental that it is Lopakhin who follows up Gayev’s comment by stating that “Yes, time flies.” Gayev replies “Who?” as if ignoring Lopakhin and Lopakhin repeats “I say, time flies” as a way of saying “if you didn’t get it the first time, then maybe you’ll get it the second.” Gayev again ignores him and says: “It smells of patchouli here” (Orchard, 1302). The allusion to patchouli is clear since the oil derived from the plant leaves is often used as a scent fixative in perfumes and fragrances, as well as to mask strong odors. In the sense that Gayev is using it the implication is that something “smells...