The Janus Head of Pride

Between 1945 and 1949, the American artist Paul Cadmus created a series of seven paintings depicting the Seven Deadly Sins.

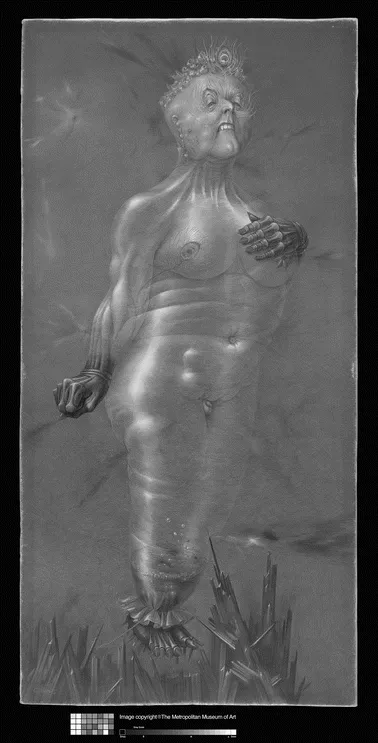

Pride was one of the series’ first paintings (Fig.

1.1).

1 While much of the painting is dominated by grays, dark greens, and blues, there is also a preponderance of an aristocratic purple. This purple is especially prevalent in the painting’s central image, adding to the figure’s evocation of haughty arrogance. With its up turned and rather hooked nose and narrowed eyes, the figure looks down disdainfully on the viewer. The figure’s right hand clenches in a severe and controlling fist. The left hand, also metallic and severe, is poised over the breast in a gesture of self-satisfaction and covers part of a gold, star-shaped, military-style medal. Besides using military accouterments, Cadmus also evokes pride’s showy vanity with peacock feather imagery, imagery that accentuates the other breast and that is repeated in the eyes and in the crown of the figure’s tightly curled gold hair. The figure’s somewhat bulbous face matches those same qualities in the torso and legs. In fact, most of the figure is a large, semi-transparent balloon, and this is even more pronounced as that balloon is tied together at the feet, from which emerge severe and metallic feet, similar to the hands. The whole figure is loosely tethered to a rocky landscape, seems inflated by some boiling, fetid liquid at the lower legs, and appears to already emit some of its gas due to a puncture by the landscape’s jagged outcropping. Finally, while the figure seems to have female features, the groin clearly displays small male genitalia. Cadmus’ painting powerfully conveys the vanity, arrogance, self-aggrandizement and self-satisfaction, disdain, and ironfisted control (that would compensate for a generative smallness and fundamental emptiness) that make pride so abhorrent.

It is significant that Cadmus created this work and the entire Seven Deadly Sins series just after the Second World War. The series distills with gruesome force the fundamental vices that resulted in the war’s nightmare of human cruelty and evil. In this context, Pride’s clenched iron fist may allude to the various forms of wartime abuse of power.

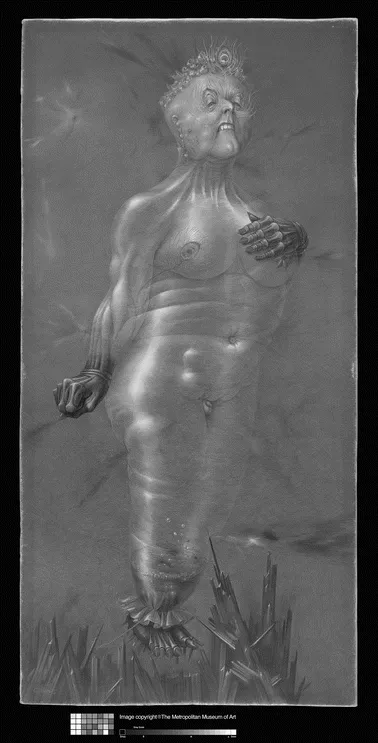

Where Paul Cadmus powerfully shows pride’s negative face, Aaron Douglas shows its positive aspect. About 15 years before Cadmus’ painting, Douglas created his depiction of Harriet Tubman (Fig.

1.2).

2 At the center of the work is the silhouette of the Underground Railroad’s powerful heroine breaking the shackles, striding forth confidently, and looking back as if to invite others to follow her to freedom. Behind Harriet are a variety of figures weighed down by the burdens of slavery and oppression. A cannon barrel smokes up from Harriet’s feet. This barrel is at the center of concentric circles, graphically illustrating successive waves of Harriet’s impact. The figures to the right of Harriet include a farmer, what appears to be a teacher, and two children, one holding a book. Cube or pillar-like mountains loom in the background.

Support for the idea that the female figure to the right of the painting is a teacher comes from the fact that the painting was created for Bennett College, a historically black women’s college. Douglas’ depiction of Harriet Tubman shows her as an ideal exemplar for the students of Bennett College. Her courage and leadership were instrumental in ending slavery and in continuing efforts for women’s suffrage. Just as Harriet leads some of the figures out of slavery’s oppression, so this woman could inspire black female college attendees to overcome continued racism and discouragement as they struggle toward a better world. Those in the present look back to Harriet and honor her legacy by continuing to carry it forward.

Douglas’ painting is not called pride, but it nevertheless demonstrates the positive face of this Janus term. The positive side of pride is associated with confidence. That confidence can be personal and centered in a sense of satisfaction or attainment by an individual, or it can be a sense of strength and belonging via the attachment to a larger group or cause. In this respect, Douglas offers a powerful version of Black pride. Black pride and other forms of ethnic and/or identity pride, including gay pride, provide a powerful antidote against the oppression of racist and homophobic cultural forces. Pride provides a sense of dignity and place, connecting one with a cause, a legacy, and a vision for which to strive. Pride heals, frees, lifts, and encourages.

So what are we to make of the concept of pride? Is it an auto-antonym like the verb “to dust,” which can mean to remove dust, as when you dust your apartment, but it can also mean to sprinkle lightly, as when you dust doughnuts with powdered sugar? This fundamental question about the nature of pride is half of what this book answers. The other half is a parallel question about the nature of humility.

The Janus Head of Humility

Just as Paul Cadmus’ painting shows the ugly and pathological side of pride, the Griselda story shows that side of humility.3 The Griselda story comes from oral folklore, but one of its earliest written versions appears in Boccaccio’s Decameron. In this version, the Marquis of Sanluzzo marries a poor peasant girl, Griselda, and then, to test her obedience and devotion, subjects her to a number of trials. His first trial is to take their newborn daughter from her mother such that the mother believes that the child is killed. The second trial comes with a similar fate of the couple’s second child, a son. When the Marquis notes his wife’s unwavering devotion, he subjects her to a third trial, wherein he divorces her, tells her that he plans on marrying another woman, and sends her back to her father. The Marquis’ final trial comes when he demands that Griselda return to prepare the palace for his upcoming wedding. When she dutifully agrees, working tirelessly in her debasing peasant clothing until all is prepared, Griselda is finally rewarded for her humility with the return of her two children (who were secretly and carefully raised by the Marquis’ extended family) and her place as the Marquis’ wife.

The face of humility presented in the Griselda story is ugly and pathological, because humility here robs the agent of power to positively affect the world around her. When Griselda’s first and then her second child are threatened by the hand of her infanticidal husband, Griselda’s humble submission to him keeps her from the normal responsibility she has toward both her children and her husband. She passively witnesses what she believes are murders, thereby at least tacitly assenting. How could a mother, or wife, or person do such a thing and be held up as a virtuous example? When she says to the Marquis, “My Lord, think only of making yourself happy and satisfying your desires and do not worry about me at all, for nothing pleases me more than to see you happy,” could she possibly surmise that he would be happy, first by killing their child, then by getting her pregnant again, then killing that child, followed by throwing her away and then bringing her back to disgracefully serve him?4 Some of the glaring deficiency in this example of humility is deflected in Boccaccio’s telling. When she returns home and is “grieved most bitterly” by her many losses, we are told that, “as with the other injuries of Fortune which she had suffered,” she met this one with determination and constancy.5 But the trials come not from mystic cosmic forces or an inscrutable wheel of fate; they come from her husband.

When the Marquis finally allows Griselda to “reap the fruits of her long patience,” he says that his pre-established goal for these trials was to “teach [Griselda] how to be a wife.”6 One of the ugliest aspects of this story is how it might teach both men and women what to expect of wives. A wife is to consider herself low if not unworthy of her husband/Lord. She allows herself to be taken from her home, stripped naked, dressed in clothing of his making, and then expected to graciously and flawlessly act as wife, mother, and consort. When he does something seemingly out of character, even if it is homicidal, she is to submit humbly to his will and wisdom. Putting his needs first, paramount of which is his happiness, she unwaveringly trusts in his benevolence in spite of obvious evidence to the contrary.

There is an additional element of this story that we should consider. That element is the Marquis. Right from the start we are told that the Marquis’ attention is completely consumed by hawking and hunting. In fact, the Marquis was “never thinking of taking a wife or having children.”7 He is only persuaded to find a wife by the constant begging of his people. He claims that his people “wish to tie [him] up with these chains.”8 Not only is the Marquis afraid of the bonds and obligations of marriage, but, at the end of the story, he reveals that when he decided to marry, “I greatly feared that the tranquility I had cherished would be lost.”9 In response to these fears, fears of the vicissitudes of intimate relationships, the Marquis takes several steps. First, he locates a young woman who is clearly his social inferior. He relies on social pressures to keep her in check. Furthermore, she lives in awe of his authority and grandeur. She does not have the example of a strong mother and instead seems to simply replace her father when she married the Marquis. In marrying her, he requires that she publicly promise that she would “always try to please him,” “would always be obedient,” and similar vows that would assure him of her complete subservience.10 Apparently unsatisfied by her outward signs of devotion, he presses upon her the story’s excruciating trials. By the end, he says, “I am your husband, who loves you more than all else, for I believe I can boast that no other man exists who could be as happy with his wife as I am.”11 The Marquis is happy because now that he has witnessed his wife’s complete constancy and submission, he is no longer afraid.

The Marquis’s confidence, born of his control of another, shows how humility is often what the powerful and frightened want of others. Terrified of interdependence, as well as the risks and contingencies of life, the frightened yearn for the sort of humility on the part of others that will make those people reliable, predictable, and controllable. They seek a tranquility that comes from the absence of different points of view, criticism, dissent, and disconfirmation. Wracked with insecurity, the frightened are compelled to constantly test those around them. In this respect, it is tellingly ironic that the Marquis, who wants peace and a reliable spouse, gives his young, vulnerable wife neither peace nor loving reliability. But for all of the Marquis’s careful testing, can he really be sure that she will be as constant in the future? How can he know that she will not wake one morning to the realization of what he has put her through and determine that he is not worth it?

Another painful fear that can be seen in the story comes to the fore when we see how Griselda may be like an ideal woman, namely, the Virgin Mary. Like Mary, Griselda is poor and called to a previously unimagined high role or calling. Griselda responds to her call with Marian humility. Both women lose beloved children, but both are ultimately blessed for their constancy. But it is deeply problematic to create a parallel between Mary’s relationship with God and a human woman’s relationship with a human man. Men are not gods and should not be followed or obeyed or worshipped as such. As this book will explore, women who submit to men as if they were gods as well as men who ask for such submission inevitably suffer.

If the humility evident in Boccaccio’s telling of the Griselda story is ugly and pathological because it is an obedience and submission that robs one of power and responsibility, that provides a most unhealthy mode and model of human relationships, and serves and sustains the fears of the powerful and frightened, then the opposite is the humility that can be seen in the life of Dr. Alice Stewart. Dr. Stewart is the physician and epidemiologist, famous for her discovery of the dangers of fetal x-rays. In 1999, Gayle Greene published a biography of the scientist called The Woman Who Knew Too Much: Alice Stewart and the Secrets of Radiation. Dr. Stewart, as she is described in this book, is an example of how humility can be a form of submission that reinforces power and responsibility, that provides a healthy mode and model of human relationships, and that can ultimately inspire courage.12

Like Griselda, Dr. Stewart, as Greene describes her, has many trials to overcome. In the 1920s, when Dr. Stewart attended Cambridge, women and minorities were allowed to attend, but were not welcomed. She says this about her first lecture:

It was a large room, an audit...