![]()

Chapter 1

THE HAGENBECK-WALLACE

CIRCUS

By 1918, the name of Ben E. Wallace had stood out in the circus world for more than thirty years. In fact, it had stood out since before 1886; that was the year the “Great Wallace Show” took to the rails for the first time.

Although technically a veteran of the Civil War, Wallace was not a combat soldier. He was an eighteen-year-old bounty soldier, a hired substitute for Robert F. Effinger, who was enrolled on February 28, 1865, into Company K of a reorganized Thirteenth Indiana Volunteer Infantry Regiment then encamped at the west edge of the government center for LaPorte County. A little more than four months later, shortly after arriving at New York Harbor, Wallace was discharged from Federal service and returned home.1

That home was a growing community named Peru, the center of local government for Miami County, Indiana, and it was becoming a bustling railroad transportation hub. It was also adjacent to the nonreservation lands owned by members of the Miami Indian tribe who remained on individually owned farms after the majority of the tribe members had been forced westward nearly twenty years earlier.

Once back in Peru, Wallace soon developed a modest and growing horse-trading business, which, by 1881, he was advertising as “the largest livery stable in Indiana.” Author Nancy Newman, in an article that appeared in the local newspaper about one hundred years later, wrote about how Wallace got into the circus business:

In 1882, Wallace, who had been interested in circuses for several years, attended a sale of equipment of the W.C. Coup show. The large railroad show had passed through Peru on its way to Detroit. Heavily mortgaged, it could not meet its financial obligations and was declared bankrupt.

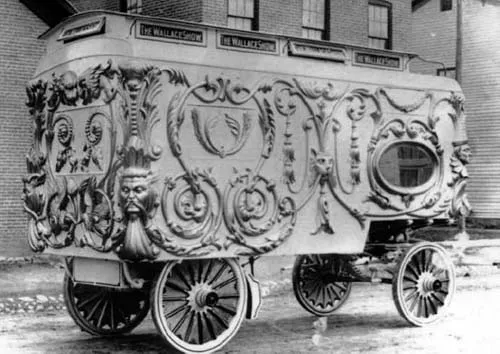

Wallace returned from the sale with six or seven rail cars full of tents, poles, costuming and other equipment. He attended a sale for another show in Texas, returning with several rail cars of horses. He purchased other animals in Chicago, and in December he contracted with a local firm, Sullivan & Eagle, for construction of some ornate wagons.2

Throughout 1883, Wallace continued to build up his circus by hiring the best performers he could find. Finally, after recovering from a late January 1884 fire that killed some of his exotic animals, the first Wallace Show gave its inaugural performance in Peru and then went bravely forth in the spring of 1884.3

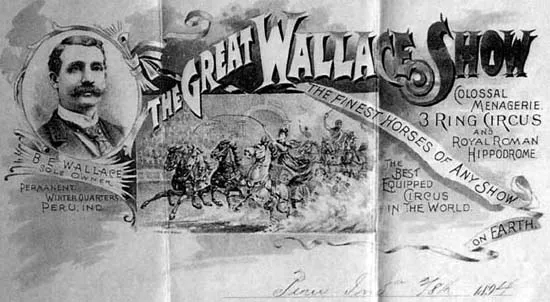

Traveling as a horse-drawn road show, the Wallace and Co.’s Great World Menagerie spent most of its time in southern Indiana, Ohio, West Virginia and Kentucky and, quite possibly to the amazement of all its investors, returned a sizable sum. After another successful tour in 1885 that saw the one-ring show traveling in a procession of twenty-six wagons, Wallace made the decision to expand his next performance route throughout the nation. He also decided to change its name. Consequently, in 1886, the Great Wallace Show took to the rails and traveled by train for the first time.4

Ben Wallace had an eye for good horseflesh, and by 1886, he was considered one of the top horse experts in the country. He also had the gift of showmanship. Within a few years, his Great Wallace Show grew from a mere fifteen cars to more than forty freight and wagon carriers that held a massive big top tent, a menagerie tent, two horse tents, the sideshow tent, a cookhouse and various sleeping quarters for the performers.5

The Wallace Winter Quarters were located on an old farm that was once owned by Gabriel Godfroy, son of the last Miami Indian chief to live in Indiana. Wallace bought the 220-acre farm when Godfroy lost the ability to have the farm counted as part of the Miami Indian tribal lands. It was the state and local tax assessed on the property that forced that sale. Wallace bought the Godfroy property in 1892 and continued buying other farmlands (there were several other Indian farms nearby in the same situation) until he owned all land on both sides of what is now Indiana State Route 124 all the way to the eastern edge of Peru, Indiana, a distance of two miles. The Godfroy Farm and the other farms nearby, situated on the north side of the Wabash River at the confluence point where the Mississinewa River joins the Wabash, were notorious not only for being some of the best crop-producing acreage in the area but also for being subject to annual floods.

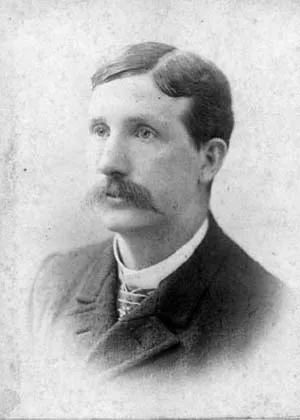

A young Benjamin Wallace. Courtesy Miami County Museum.

One of the original wagons of the Wallace Show. Courtesy Miami County Museum.

The Wallace Show bandwagon. Courtesy Miami County Museum.

An 1894 flyer for the Wallace Show. Courtesy Miami County Museum.

Finally, in July 1892, the law of averages caught up with the Great Wallace Show. After logging thousands of miles on the nation’s ribbons of steel, the Wallace Show experienced its first railroad train wreck. Twenty-six of the Wallace Show’s highly prized, performance-schooled horses, worth a total of at least $5,000, were killed.6 The Show would spend a lot of money and months of training to replace them.

Eleven years later, at the town of Durand, Michigan, fate again caught up with the Great Wallace Show. On August 7, 1903, the show train was arriving at the local rail yard after having been conveyed from its departure point as two separate train sections. The first train section, traveling several minutes ahead of the second section, was safely in the Durand rail yard. The second circus train section did not slow down as it approached and entered the yard at its regular traveling speed. It slammed into the rear of the first section, killing twenty-six men, including the trainmaster, and an unknown number of railroad employees. Several animals were also killed. The engineer of the second section later claimed that his air brakes failed even though subsequent testing revealed that they were in perfect working order. This would become the second worst circus train wreck ever.7

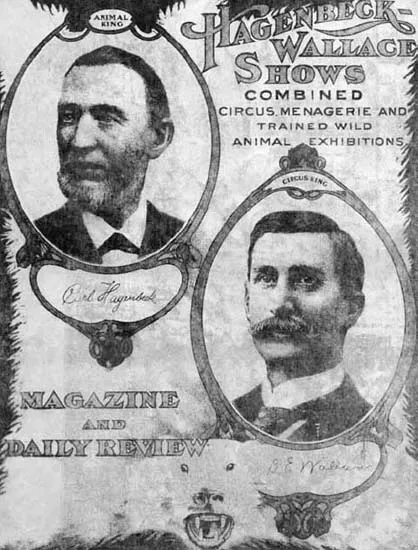

By some adroit legal maneuvering, the details of which are still not clear, in 1907 Ben Wallace obtained the famous animal circus of Carl Hagenbeck, Chicago’s version of New York City’s P.T. Barnum show. The price reportedly paid was $45,000, truly a princely sum in that day and age. Immediately, Wallace changed the name of his show to the Hagenbeck-Wallace Circus and began advertising the show as the “world’s highest-class circus.”8 In truth, it may actually have achieved that classification, for it was ranked beside both the Ringling Brothers and the Barnum & Bailey Circuses. The size of the augmented circus in 1907 required that it travel as two completely separate train sections, with each section numbering at least twenty-eight rail cars.

A 1914 advertising insert of the combined Hagenbeck-Wallace Shows. Courtesy Miami County Museum.

Evidently, Carl Hagenbeck was not very happy with Ben Wallace’s business reputation. Some people have since claimed that Wallace’s philosophy was, perhaps, best summed up in an admonition he gave to his employees, “Shoot square as long as you are in Peru.” True or not, the man who spent his first eighteen adult years as a horse trader in Peru desired, and got, the respect and honor of his hometown.9 What he thought about the opinion of the rest of the world is now unknown.

Despite a 1908 lawsuit filed by Hagenbeck in the courts of Cook County, Illinois, the combined show remained the Hagenbeck-Wallace Circus for evermore. And the newest version of the Hagenbeck-Wallace Circus was no nickel-and-dime affair either, even though Wallace made his living off those nickels and dimes. According to one of Peru, Indiana’s newspapers (most likely the Peru Republican), at the end of 1907, after Ben Wallace had bought out the interests of three other partners for $125,000, the Hagenbeck-Wallace show was completely owned by Wallace and John Talbot of Denver, Colorado.10

That was the way things stood until the latter part of March 1913, when the advent of a spring storm system proved devastating to the Midwestern states drained by the Ohio River. Marked by a massive tornado that caused widespread destruction in Omaha, Nebraska, the storm system continued eastward up the Ohio River Valley, dropping two inches of relatively warm rain on the snow-covered and frozen ground of southern Ohio and Indiana. The rain and melted snow could only drain off into the lakes, creeks and smaller rivers, pushing the Miami and Wabash Rivers, which eventually received that runoff, well beyond flood stage. Newspaper reports of between two and five thousand deaths in Dayton, Ohio, and between two and four hundred deaths in Peru, Indiana, were printed on March 26 and, even today, still testify to the severity of the overall situation.11

The departure parade of the Hagenbeck-Wallace Circus in Peru, Indiana, 1909. Courtesy Miami County Museum.

The departure parade passing Ben Wallace’s house in Peru, Indiana, 1909. Courtesy Miami County Museum.

Fortunately, those newspaper reports would prove to be incorrect, at least as far as the deaths of Peru citizens were concerned, but the overall effect of the flood was very costly nonetheless. Ben Wallace and his family actually did not live on the winter quarters grounds (he had an imposing home in Peru), but a good many men did live on the grounds, and seventy-five of them were trapped on the property by the floodwater. The location of Wallace’s home did not prevent him from being trapped, however. The floodwater was knee-deep around his house, and he, like every other city resident, sought shelter on the upper floors of whatever second-story building was available.

Several days would pass before a firm estimate of the flood damage could be made. Finally, on March 29, the reports that the Wabash River had dropped nine feet in Peru and would be completely gone by that night, along with another that the death list had a total of twenty-eight people, were sent to all newspapers. However, those reports would not begin to list the costs of the damages to individual homes, business or industries in and around all of the affected cities. Later, it was reported that damages to the Hagenbeck-Wallace Circus would total over $150,000. That figure included the loss of eight elephants; one of the dead elephants was found lying next ...