![]()

1

“WHERE A GOAT CAN GO,

A MAN CAN GO”

With the trained eye of an army engineer, Lieutenant William Twiss gazed over the terrain he saw atop Sugar Loaf Hill, later known as Mount Defiance. It was about two o’clock in the afternoon on July 5, 1777. American defenders had lost a grip on their outer lines around Fort Ticonderoga three days earlier. The thirty-two-year-old officer was accompanied by Major Griffith Williams, commander of Burgoyne’s artillery corps, and Brigadier Simon Fraser, the latter using “an excellent compass” to guide the party up the hill. They joined Captain James Craig, forty light infantrymen and a handful of Indians who had been dispatched the day before by Fraser to occupy Sugar Loaf. Twiss had already garnered accolades from General Guy Carleton, the commander of British forces in Canada. Carleton reported that he recognized Twiss’s “particular distinction” in the previous year’s campaign. Now that British forces had gained access to the mountain, Twiss would have another opportunity to shine. It was an “abominably hot” summer day, Fraser later remembered, but the redcoat officers’ arduous climb up the wooded slope yielded much promise for the British army facing Fort Ticonderoga.9

Twiss had been assigned as an aide to Major General William Phillips, in addition to his duties as chief engineer for Burgoyne’s army, which had left Canada on June 16, bound for Albany. Phillips was second in command in Burgoyne’s army. But more importantly, Phillips was an accomplished artillery officer who had gained fame during the Seven Years’ War in Europe. His handling of British guns at the 1760 battle of Warburg became a textbook example of how artillery could attack alongside cavalry. Twiss and Williams had been ordered to climb the 853-foot hill to see if it offered an opportunity for the placement of an artillery battery. Cannon atop the undefended position would dominate the American army’s position at Fort Ticonderoga on the west side of Lake Champlain and at Mount Independence situated on the lake’s east side. It would require a one-milelong road cut for the guns, but the rewards were worth it, Twiss argued. Once a battery was in place, the Americans could not “make any material movement or preparation [during the day] without being discovered, and having their numbers counted,” Burgoyne later reported.10

Modern-day view of Fort Ticonderoga taken from Mount Defiance. Courtesy of Sandy Goss/Eagle Bay Media.

Possession of Sugar Loaf would put the American position well within the range of Burgoyne’s twelve-pounders. To support Twiss’s report of the advantages offered by Sugar Loaf’s elevation, General Phillips allegedly claimed, “Where a goat can go, a man can go, and where a man can go, he can drag a gun [behind him.]” Whether Phillips actually uttered these now famous words, his biographer has concluded that this statement was “a precise reflection of Phillips’ battlefield perspective” and “his personal philosophy.” Phillips’s gutsy leadership and the gritty determination of four hundred British foot soldiers paid off as two guns were manhandled up the hill within twenty-four hours.11

Major General Arthur St. Clair (1737–1818). Courtesy of the National Archives, 148-CCD-43.

A logical question is: why wasn’t Sugar Loaf fortified by the Americans to protect it from British seizure? The Ticonderoga promontory was a system of earthworks, redoubts and blockhouses, all constructed over a two-year period to tie together the old fort on the lake’s west side with the newly fortified encampment across the lake. Montcalm’s old French Lines from 1758 were incorporated into the scheme. But no works were ever built on the mountain that overlooked the La Chute River southwest of the fort. An American staff officer named John Trumbull had argued for a redoubt on top of the mountain, but his commander at the time, Horatio Gates, rejected his young aide’s proposal. Gates felt that to tie Sugar Loaf into the existing defensive plan would require more time, money and manpower than it was worth. But the major deterrent for a fortification on Sugar Loaf was water. There was no reasonable way to supply the isolated garrison with water, especially one under siege. Sugar Loaf went undefended, to Burgoyne’s advantage.12

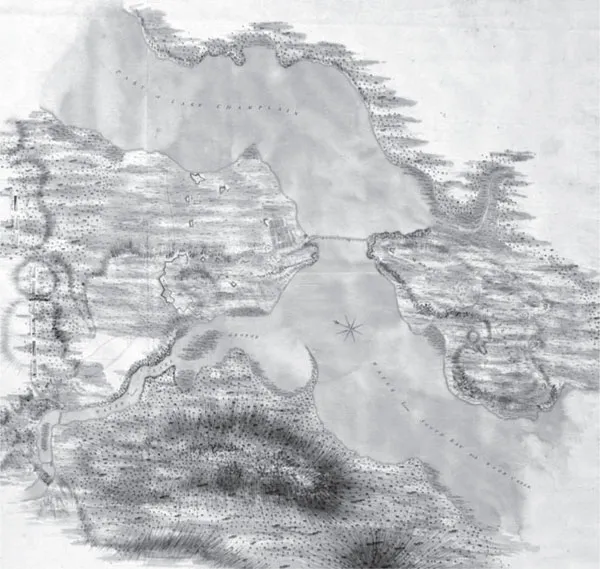

A map of Fort Ticonderoga and Mount Independence as surveyed by British assistant engineer Lieutenant Charles Wintersmith in 1777. This map shows the bridge across Lake Champlain connecting the two fortifications before St. Clair’s evacuation on July 6, 1777. Courtesy of the Fort Ticonderoga Museum Collection and Chris Fox, curator.

Three days prior to Twiss’s excursion, Burgoyne had begun to disembark his army for an attack or, if need be, a siege of the American fortifications. At Three Mile Point north of Fort Ticonderoga, the redcoat contingent of Burgoyne’s command, led by Brigadier Simon Fraser’s Advance Corps along with some Loyalist scouts and Indian allies, was put ashore.13 On the east side of Lake Champlain, Major General Friedrich Baron von Riedesel’s German command, mostly soldiers hired from the principalities of Brunswick (Braunschweig) and Hesse-Hanau, was unloaded. Burgoyne’s plan was to create a double envelopment of the American lines, with Fraser investing Fort Ticonderoga and Riedesel cutting off a Patriot retreat by crossing East Creek above Mount Independence. The thirty-nine-year-old German general, a veteran of the Seven Years’ War, was expected to block the military road that led out of the eastside fortifications to the commonly called New Hampshire Grants (present-day Vermont). The name was shortened to the “Hampshire Grants” by settlers who moved there.14 Burgoyne had masterminded a brilliant military strategy for capturing Fort Ticonderoga and destroying the enemy. However, like so many well-conceived military operations, its execution did not go as planned.

General Arthur St. Clair, the newly appointed American commander at Fort Ticonderoga and Mount Independence, watched Burgoyne’s movements with great anticipation. St. Clair had only arrived at the rebel fortifications on June 13, three days before his adversary sailed from Canada. The Scotsman found the Ticonderoga works grossly undermanned and badly in need of repairs. On the Fort Ticonderoga side, the Patriots had improvised on remnants of the old French Lines west of the fort by adding some redoubts. The French Lines had been built nearly twenty years earlier when another fort commander, Marquis de Montcalm, had successfully defended Fort Carillon (Ticonderoga’s previous name) against the British in 1758. On Mount Independence (formerly known as Rattlesnake Hill), the Americans had built a star-shaped fort with barracks inside, along with several blockhouses, a hospital and a large fortification called the Horse-Shoe Battery.

To connect the main fort and French Lines with the works on Mount Independence, a floating bridge supported by sunken wooden caissons had been constructed. To protect the bridge from enemy ships ascending Lake Champlain from the north, a chain and log boom was anchored above the bridge on either side of the lake. When St. Clair arrived at the promontory in June, much work still needed to be done to make the installation fit for military defense. The forty-year-old Scotsman immediately set fatigue details to work strengthening all parts of the terrain. Unfortunately, progress on the fortifications was painstakingly slow when alacrity was essential. Despite St. Clair’s best efforts, the steps he would take and the decisions he would make would be roundly criticized, resulting in a formal court-martial a year later.

Early in the War for Independence, Fort Ticonderoga had been captured by a surprise attack jointly led by Benedict Arnold and Ethan Allen and his Green Mountain Boys. In May 1775, the lightly guarded British post was a valuable prize for the Continental Congress. Several months later, the Congress’s newly appointed army commander, George Washington, soon saw value in the old fort, a relic of the French and Indian War, along with its sister fort at Crown Point. It was the two forts’ contents, not their strategic locations, that appealed to the Virginian at the time.

During the siege of Boston—which had followed clashes at Lexington, Concord and Bunker Hill—New England militia regiments under Washington’s command had bottled up the British army in the Massachusetts town. Among the redcoat generals stationed in Boston at the time were three men who would play major roles in the 1777 campaign two years later: John Burgoyne, William Howe and Henry Clinton. It’s fair to say that Burgoyne’s observation of the battle of Bunker Hill from Boston’s Copp’s Hill probably influenced his later decision to mount guns on Mount Defiance first, rather than risk an immediate frontal assault on St. Clair’s works at Ticonderoga.

Six months after the capture of Fort Ticonderoga, Washington seized the opportunity presented by the captured contents of the fort. The forty-threeyear-old general ordered his chief artillery officer, Colonel Henry Knox, to deliver as many cannon as he could haul from the Lake Champlain forts down to Albany and then over the Berkshire Mountains in western Massachusetts to Boston. It was an arduous assignment, but the competent, rotund Knox carried out his orders flawlessly. Some fifty-nine guns and mortars were delivered to Washington. Once the cannon were mounted on Dorchester Heights overlooking Boston Harbor, the British army was forced out of the city on March 17, 1776.

The Americans would hold Fort Ticonderoga from its capture in May 1775 until Burgoyne approached the fortress in June 1777. Patriot forces were lucky in October 1776 when British major general Guy Carleton’s invading army was stalled at Lake Champlain’s Valcour Island by the plucky leadership of a former merchant sea captain turned army officer named Benedict Arnold. Although defeated by Carleton in a pounding naval engagement, Arnold’s dogged tactics delayed the British invasion long enough into the autumn months that Carleton was forced to rethink his campaign options. Despite urging from his subordinate commander, John Burgoyne, to continue the campaign, New York’s approaching winter made further action unfeasible in Carleton’s mind. The future Lord Dorchester retreated down the lake back to Canada; Fort Ticonderoga was safe for another season. As one historian has concluded, “Had Ticonderoga been taken [by Carleton] and held that coming winter, Burgoyne’s campaign of 1777, starting from that point, would have almost certainly succeeded.”15

The intervening months at Fort Ticonderoga after Carleton withdrew were mostly peaceful for the garrison and its commanders. Food and tent shortages, disease and frigid weather sapped the men more than gunfire. A soldier was more likely to freeze to death than die of a gunshot. The fort’s commander during the winter months, Colonel Anthony Wayne, lamented the number of men in the ranks who were daily falling from fever, “camp distemper” and other maladies. At a post that General Schuyler claimed needed 10,000 soldiers to defend it properly, Wayne could barely muster 1,600 Continentals, supplemented by a few hundred New England militiamen. When the Pennsylvania officer was promoted to brigadier general and ordered to join Washington’s army in April 1777, he tried to put a good face on his former command. Wayne inaccurately reported to Washington that “all was well” and that the fort “can never be carried, without much loss of blood.”16

Wayne’s opinion might have influenced Washington’s belief in Fort Ticonderoga’s impregnability when he was considering dispatches from Schuyler in June 1777. Despite Wayne’s optimism, it was a miserable situation that St. Clair walked into two months later. St. Clair later wrote, “Had every man I had, been disposed in single file on the different works and along the lines of defence [sic], they would have been scarcely within the reach of each other’s voices.”17

Brigadier Simon Fraser (1729–1777). Courtesy of the Guttenberg Project.

A month after Wayne penned his misleading report to Washington, things were racing forward at British headquarters in Quebec. The campaign of 1777 would see Burgoyne, who was more aggressive than the cautious Carleton, leading troops. The man calling the shots in London, George Germain, hated Carleton; the feeling was mutual. Carleton would remain in Canada as governor, while his former subordinate sailed south with grand fanfare. Now, in July 1777, the mighty fortress that some would call the key to the continent was in Burgoyne’s sights, a prize that had eluded his commander the previous year.

With regimental bands playing, drums beating and flags flying, Burgoyne simultaneously landed the two wings of his army at Three Mile Point and north of East Creek. Investment operations against Fort Ticonderoga and Mount Independence had begun. His general orders the previous day reflected the pomp and circumstance of the occasion. He wrote, “We are to contend for the King, and the constitution of Great Britain, to vindicate Law, and to relieve the oppressed—a cause in which his Majesty’s Troops and those of the Princes his Allies, will feel equal excitement.” Adding the zest of an acclaimed author, the general continued, “The Services required of this particular expedition, are critical and conspicuous. During our progress occasions may occur, in which, nor difficulty, nor labour nor Life, are to be regarded.” Finally, Burgoyne haughtily stated, “This Army must not Retreat.” He would hold steadfastly to this caveat until all hope was lost three and a half months later.18

Brigadier Simon Fraser made short work of the anemic American defenses outside the French Lines. The forty-eight-year-old Scotsman was a career officer and veteran of the French and Indian War in America who commanded Burgoyne’s Advance Corps, a highly specialized unit of shock troops. As preparations were underway for the upcoming campaign, there was an army rumor that if Fraser did a good job with his assignment, he would be made Earl of Lovat. This honor would restore his family’s confiscated lands, lost when a previous earl had backed Bonnie Prince Charlie in the Scottish rebellion of 1745. An experienced combat commander, Fraser had developed a close personal friendship with Burgoyne during their previous year in Canada. Fraser served in the present campaign at the commanding general’s personal request. Burgoyne was happy to praise his brigadier to Lord Germain, writing of Fraser’s “uniform intelligence, activity, and bravery which distinguish his character on all occasions, and entitle him to be recommended in the most particular manner to his Majesty’s notice.” The feelings were mutual. Fraser considered his commander “a fine agreeable manly fellow.” Burgoyne was also thought to have said that Fraser never begrudged “a danger or care in other hands than his own”—a prescient remark that would be fulfilled on the morning of July 7, 1777.19 Fraser was the right man to command such a nonpareil unit.

The Advance Corps was made up of a grenadier battalion, the physically largest and most rugged men in each regiment; a battalion of light infantry, consisting of each regiment’s most agile and fittest fighters; and eight companies of Fraser’s own Twenty-fourth Foot, a so-called hat battalion. In the eighteenth century, British army grenadiers wore high mitered helmets to increase their height appearance, the light infantry had leather caps and the regular companies were accoutered with the traditional tricorn hat. Fraser was lieutenant colonel of the Twenty-fourth Foot, effect...