![]()

1

THE SOUND OF MUSCLE SHOALS

You ask me to give up the hand of the girl I love

You tell me I’m not the man she’s worthy of

But who are you to tell her who to love?

That’s up to her, yes, and the Lord above

You better move on.

—“You Better Move On,” Arthur Alexander (later covered by the Rolling Stones)

Pore over books and historical records focusing on northwest Alabama, and the bulk of what you’ll find will cover the Tennessee Valley Authority, a government-owned utility launched in Muscle Shoals in the 1930s. A 1950s Muscle Shoals Chamber of Commerce brochure indicated that the area had two radio stations, fewer than twenty-seven thousand residents and little to do (most of the listed activities—a football stadium, lighted baseball parks, playgrounds and so on—could have been based at area schools). It isn’t until that decade that music started showing up in a significant way.

A man named Dexter Johnson can claim credit for the area’s first recording studio, which he set up in his home in 1951. Johnson established a legacy not only for the region but also for his family; his nephew Jimmy Johnson grew up to become the Muscle Shoals Rhythm Section’s guitarist. The younger Johnson’s studio now sits cater-corner from his uncle’s garage studio.

Although Dexter Johnson’s initial forays into recording began in the earlier part of the decade, Shoals music didn’t hit the professional level until 1956. Tune Records was a partnership formed by James Joiner, Kelson Herston, songwriter Walter Stovall and attorney Marvin Wilson. The studio focused on pop and country music, including songs written by Phil Campbell’s Billy Sherrill and Franklin County’s Rick Hall.

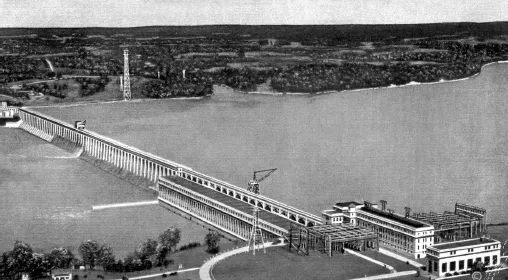

Muscle Shoals, circa 1933. Library of Congress.

This photograph of the Muscle Shoals Bridge appeared on a 1950s-era postcard published by Dexter Press. Auburn University Libraries Special Collections & Archives Department.

A 1940s postcard of the Wilson Dam in Muscle Shoals, Alabama. Author’s collection, Aero-Graphic Corp.

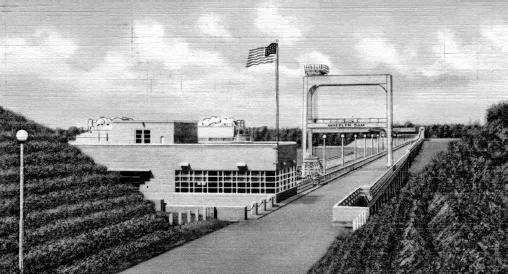

A postcard of Wheeler Dam in the Shoals area of Alabama. Author’s collection, Anderson News Company, Florence, Alabama.

The first-known recording studio in the Shoals (shown here in the picture hanging on the wall at the Alabama Music Hall of Fame) was at the home of Dexter Johnson, who is remembered at the Alabama Music Hall of Fame. Johnson was the uncle of Muscle Shoals Rhythm Section member Jimmy Johnson. Author’s collection.

“It may not have been Nashville or Memphis, but the music scene in Florence was suddenly a reality, and everybody was hungry for a hit,” Younger wrote.

When Percy Sledge, a hospital orderly at the time, came calling in 1966, though, Joiner sent him elsewhere. Sledge’s sound, which he developed by humming while working in cotton fields, didn’t jive with the more pop-sounding music of Tune Records, and so he turned to Norala Sound Studio. Rick Hall, who by then owned FAME Studios, let his friend Quin Ivy borrow his rhythm section for the recording of “When a Man Loves a Woman.” The song went to number twenty-two on Billboard’s Top 100 for the year and attracted other talent to the Shoals area. It was later covered by artists such as Michael Bolton, Rod Stewart and Bette Midler.

But the region’s music business had a long way to go before it attracted such big-name talent. First, the local folks needed to find a bit of success. Perhaps because of the region’s proximity to Nashville, Tennessee, area musicians would often make the pilgrimage to the country music capital. But the demos they would tote were sometimes cut back at home. A local radio station helped musicians recording those demos as they sought songwriting careers. The quality was iffy, but the tapes sometimes brought the songs to the attention of bigger recording artists. In 1957, teenager Bobby Denton recorded the Joiner-penned “A Fallen Star” at Tune Records and began to see some success.

“It became a regional hit, almost a big hit,” then Alabama Music Hall of Fame executive director David Johnson recalled in an interview with the (Mobile, AL) Press-Register. Denton, who later became a state senator, has noted that it is believed to be the first song recorded commercially in Alabama.

That inspiration was all it took for other aspiring musicians to jump in. Others saw Tune and Norala’s success and decided to pursue their own music industry dreams. In 1958, Tom Stafford teamed up with Joiner, who was mostly a silent partner, to form the record label Spar Music Company. Spar Music opened in 1959 and also began working to create demos to draw attention from Nashville. Stafford, Billy Sherrill and Rick Hall also opened FAME Recording Studios in 1960. The partnership dissolved soon after, with Hall retaining the name. Stafford retained the studio, artists and recording label. Spar eventually disappeared while FAME became the stuff of legends.

“They said I worked too hard,” Hall said to the (London) Telegraph. “So they fired me. They were thinking, by the time we get to 40 we ought to be millionaires. My thinking was, by the time I’m 30 I’ll be a millionaire.”

Hall used money loaned to him by used-car dealer Hansel Cross, whose jingles he recorded to open a new studio. Hall also married Cross’s daughter, Linda.

In 1961, a bellhop named Arthur Alexander traveled the short distance from Spar to Hall’s FAME Studios and made history. Stafford at Spar recognized that Alexander’s song “You Better Move On” had real potential, but in the previous business partnership, Stafford had not overseen the business aspect of recording. Spar remained focused on demos. So instead, Stafford sent Alexander to Hall to record a polished version of his song.

It was the song that put the Muscle Shoals region on the musical map. When he couldn’t find a label to release the song, Hall put it out on his own. The song traveled up the charts to number twenty-four. (A year later, the Rolling Stones would cover the song on the band’s debut EP. That was before the group became one of the greatest bands of all time and well before it traveled to the Shoals to record its own work.) Within a few years, the Playground Daily News noted in a 1970 article, Hall had turned a $5,000 investment into a $1-million-per-year success story.

Hall subsequently built the current FAME studio, modeled after Nashville’s RCA, and set to recording. Even in those early days, his stationery and the building’s exterior predicted success, with “Home of the Muscle Shoals Sound” emblazoned on both.

“The Shoals had its first homemade hit record, and its first homegrown star,” Lawrence Specker wrote in the (Mobile, AL) Press-Register in 2001. “It also had a recording boom on its hands: Once it had been proved that a hit record could be made in Alabama, any number of people were willing to try it.”

And so they did.

There aren’t any books specifically about Muscle Shoals…there are chapters.

—former Alabama Music Hall of Fame curator George Lair to the

(Mobile, AL) Press-Register

![]()

2

BECOMING FAMOUS

What you want

Baby, I got it

What you need,

Do you know I got it?

—“Respect,” Aretha Franklin

Recorded with the Muscle Shoals Rhythm Section at FAME Studios

This is the story of Muscle Shoals Sound Studio. But you can’t tell the story of Muscle Shoals Sound without FAME.

Rick Hall might have been in the right place at the right time when he ended up with the rights to the FAME name. But he began preparing for a career in music years earlier. Hall, a Mississippi native raised in rural Alabama, began writing songs and playing string instruments (especially guitar and mandolin) as a teen but didn’t pursue a life in music until after his wife and father died. He began writing songs with Billy Sherrill before the pair went into business with Tom Stafford at Spar.

After he formed FAME, Hall continued to write and record music. While working with musician Jimmie Hughes, Hall wasn’t certain the song they recorded, “Steal Away,” was going to be successful. Rather than finding a label for it, Hall opted to release the song himself. Its success—as well as hits like hospital orderly Percy Sledge’s “When a Man Loves a Woman,” recorded with some of Hall’s players at Quin Ivy’s nearby studio—led to steady interest in the Muscle Shoals sound.

FAME Recording Studios was established in 1959 and moved into its current location in the early 1960s. George F. Landegger Collection of Alabama Photographs in Carol M. Highsmith’s America, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division. Gift, George F. Landegger, 2010 (DLC/PP-2010:090).

And the interest included that of Atlantic Records, which, at the time, was renowned for its soul recordings and ended up releasing Sledge’s hit. Atlantic producer Jerry Wexler had established his credentials as well; while he was a writer for Billboard, Wexler introduced the phrase “rhythm and blues.” When fellow Atlantic producer Joe Galkin told Wexler he must check out a rhythm section in northwest Alabama, Wexler was initially skeptical. He insisted he needed to hear evidence of the group’s power before he would record there.

Percy Sledge’s “When a Man Loves a Woman” was proof enough that something special was happening in this corner of the state. “The song was Percy Sledge’s ‘When a Man Loves a Woman,’ a transcendent moment in the saga of Muscle Shoals, a holy love hymn that shot to No. 1 and made me realize Galkin was right: I had to get with Hall in a hurry,” Wexler wrote in his autobiography. The song spoke for the region as a whole.

“A record just walked in here that’s gonna make our whole year,” Wexler reportedly said.

So perhaps it wasn’t surprising that Wexler brought Wilson Pickett to Alabama in 1966, the same year Sledge’s hit was released. Pickett had previously recorded at Stax in Memphis, but the studio had since closed its doors to outside artists. That meant Atlantic Records–based Pickett was in need of a new location. Besides, some reports indicate that Wexler thought his artists could benefit from a change of scenery. An article that later appeared in the Huntsville (AL) Times quoted Wexler as saying, “Some sort of atrophy had set in by the middle ’60s. Just everything was running down because all the juice went out of the New York scene in that musicians were all out of licks and the arrangers were all out of ideas.”

Maybe this northwest corner of Alabama held the solution, Wexler thought. After the original players moved to Nashville in 1964, FAME’s new—and soon-to-be-legendary—rhythm section formed. Jimmy Johnson stepped in on guitar. David Hood took up the bass in tandem with Roger Hawkins’s drumming, and after Spooner Oldham left for Memphis, Barry Beckett found himself at home behind the keys. Those musicians helped set the tone for “When a Man Loves a Woman,” unwittingly setting themselves up for a long-term relationship with one of the recording industry’s most legendary producers.

That rhythm section found great success at FAME. Their predecessors recorded a number of memorable songs (“Steal Away” by Jimmy Hughes and “Hold What You’ve Got” by Joe Tex, to name two), and the new rhythm section would continue that tradition.

In fact, the studio’s reputation grew to the point that at least one musician would camp in the parking lot, desperate for a chance to play. Eventually Rick Hall took pity on that guitar player, and Duane Allman (later of the Allman Brothers) began his musical career.

Studios then operated differently from now. “We had no headphones in those days. There was a red light that came on and there’s no ‘talk back’ in the studio. It’s because of those circumstances that, it wasn’t a challenge, but I think it m...