- 372 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

For eight decades, an epic power struggle raged across a frontier that would become Maine. Between 1675 and 1759, British, French, and Native Americans soldiers clashed in six distinct wars to claim the land that became the Pine Tree State. Though the showdown between France and Great Britain was international in scale, the decidedly local conflicts in Maine pitted European settlers against Native American tribes. Native and European communities from the Penobscot to the Piscataqua Rivers suffered brutal attacks. Countless men, women and children were killed, taken captive or sold into servitude. The native people of Maine were torn asunder by disease, social disintegration and political factionalism as they fought to maintain their autonomy in the face of unrelenting European pressure. This is the dark, tragic and largely forgotten struggle that laid the foundation of Maine.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The French & Indian War in North Carolina by John R Maass in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

THE WAR BEGINS

The hostilities between Great Britain and France in America during the 1750s and early 1760s were part of a long history of conflicts between these two kingdoms dating back to the late seventeenth century and were rooted in European politics and expansion. The first of these conflicts to spill over into North America was the War of the League of Augsburg, known in the colonies as King William’s War. This minor struggle erupted in 1688, shortly after William of Orange and his wife, Mary, became England’s new Protestant monarchs once the Catholic James II was deposed. France’s power under Louis XIV during these years alarmed England, as did its fervent Catholicism and domination of Europe.

The English government also worried about French possession of territory in North America, especially as France’s lucrative fur trade posts on the Mississippi River and in the Illinois country increased and the French claimed all the land in the interior wilderness for themselves. France also posed a growing threat to England’s seaboard colonies by establishing and strengthening a string of forts, outposts and villages from Quebec on the St. Lawrence River to the Gulf of Mexico. During King William’s War, Americans in the northern colonies suffered French and Indian attacks on the frontiers, while English troops failed to take both Montreal and Quebec in 1690. The conflict in America ended in 1697, with neither side gaining any real advantage.

War flared up again in 1702 in Europe during the War of the Spanish Succession, a conflict over who would become the king of Spain after the death of Charles II in 1700. This conflict, known as Queen Anne’s War in the American colonies, was fought primarily along the border between the French and English colonies in the North, the scene of numerous raids and massacres and the destruction of towns and farms. The fighting resulted in the capture of Newfoundland and Acadia by English forces before the war’s end in 1713. The English colonies also battled Spain (France’s ally) in Florida, although the fighting in the South was indecisive.

Over two decades later, the War of the Austrian Succession (1740–1748) involved most of Europe in a group of conflicts over territorial and dynastic disputes following the death of the Holy Roman Emperor Charles VI. The British feared French supremacy in Europe and territorial gains in America and the islands of the West Indies. By 1744, the war became primarily a fight between France and Britain, although the Prussians under Frederick the Great were actively involved against their bitter Austrian enemies as well.

In America, this military contest was called King George’s War, after the British monarch on the throne at the time, George II, who reigned from 1727 to 1760. During this conflict, British military officials launched a joint land and sea expedition in 1741 against the fortified Spanish port of Cartagena in modern Colombia. The ambitious campaign included the embodiment of a large regiment of 3,373 officers and men raised in the American colonies. The expedition, an unqualified disaster for the British and colonial force, included hundreds of North Carolina soldiers, few of whom ever returned from the Caribbean theater. This war also impacted North Carolinians in September 1748, when two Spanish ships sailed up the Cape Fear River and attacked the port town of Brunswick. A small force of armed locals drove off an enemy landing party a few days later but only after citizens lost £1,000 in property and suffered several casualties.

On a brighter note, a force of New England colonists supported by British navy warships managed to capture the French fortress at Louisbourg on Cape Breton Island in 1745, although once the war ended in 1748, British diplomats returned this strategic bastion to the French as part of the peace settlement. The duration of the conflict and its financial drain eventually led the weary European powers to negotiate a truce, the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle. Signed in 1748, this treaty was more of an armistice or cease-fire in Europe, not a true end to the conflict, especially in the Americas.

The final colonial struggle between Britain and France for supremacy in North America was what Americans have come to call the French and Indian War (1754–1763), part of a global conflict now known as the Seven Years’ War or “the Great War for Empire.” Many of the old antagonisms between European powers had remained since the previous war, especially between France and Great Britain in the New World. As one recent historian has noted, “The Seven Years’ War was…essentially a continuation of the War of the Austrian Succession,” since Britain and France continued to skirmish in their colonies, on the high seas and in India.3 The Seven Years’ War quickly became a worldwide struggle, involving by 1756 France, Britain, Russia, Austria and Prussia after the initial hostilities began in the frontier wilderness of America two years earlier.

Something of a “cold war” existed after the 1748 Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle between the French in Canada and the valleys of the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers and the British colonies along the Atlantic seaboard. Both of the former belligerents sought to lure North American Indian tribes into their commercial and military spheres of influence—or at least keep them neutral. In search of trade opportunities, small numbers of British entrepreneurs began to move across the Appalachian Mountains toward the upper Ohio River Valley, while land company investors and speculators sought to obtain huge property grants to resell to future settlers. Pennsylvania and Virginia commercial interests also tried to muscle into the fur trade by establishing posts west of the Appalachians, which had long been the purview of French traders.

The colonial French government, headquartered in Quebec, sought to block these alarming English encroachments into what it considered to be its own territory, by right of earlier exploration and occupation. It feared that determined American colonists would eventually settle the fertile Ohio Country, which would block communications from New France (Canada) to the French settlements along the Mississippi River and in the Louisiana and Illinois Territories, including New Orleans. It began to construct new forts in this vast, sparsely settled wilderness to protect its scattered possessions, including the upper reaches of the Ohio River, where daring Pennsylvania, Maryland and Virginia traders and surveyors were already intruding.

As part of their new defensive measures, in 1753, French officials sent a strong force to construct a chain of earth-and-log forts to link Lake Erie with the strategic point called the Forks of the Ohio. This was the confluence of the Allegheny and the Monongahela Rivers, which combined to form the Ohio River at today’s city of Pittsburgh. When French colonial troops arrived at the Forks in April 1754, they found a small contingent of Virginia provincial soldiers already building a stockade fort there, in what the French regarded as their own domain. Virginians had also established trading storehouses opposite the mouth of Wills Creek on the Potomac River, which also displeased the French.

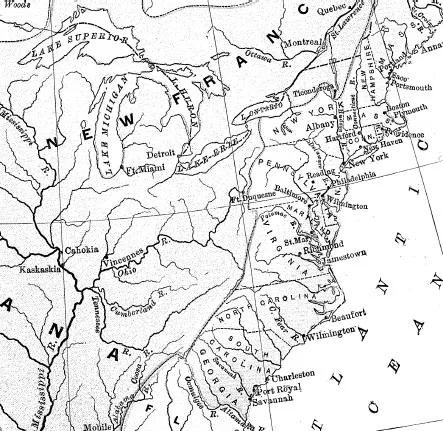

The British North American colonies and New France during the French and Indian War. George Park Fisher, The Colonial Era, 1896.

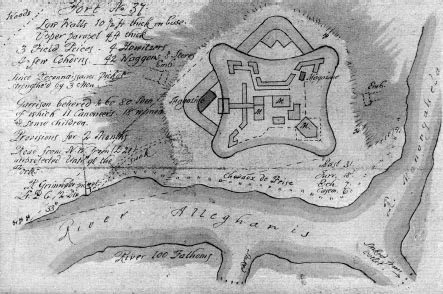

The French soldiers constructed Fort Duquesne—a square earth-and-log fort with four bastions, outer works and a palisade to the east—after forcing the outnumbered Virginians to leave the Forks. This stronghold and three smaller forts between the Forks and Lake Erie would effectively block American commercial enterprises west of the mountains if they were allowed to stand by colonial leaders. A combination of powerful Virginian and British investors, along with imperial authorities bent on defeating the French in the American wilderness, moved to evict the French from this remote area with military force in the spring of 1754—the first of three such endeavors launched against Fort Duquesne during the war.

British authorities in London reacted promptly once apprised of the French military threats on the west side of the Appalachian Mountains. The secretary of state for the Southern Department (responsible for the British Crown’s American colonies) Robert Darcy, the earl of Holderness, sent a letter in August 1753 to all American colonial governors warning them of the French danger to the west and that they should force the French off British territory by peaceful means if possible. The colonies were permitted to raise troops to meet “Force by Force,” in the words of the secretary, if the French could not be made to withdraw quietly. With few British soldiers stationed in America at the time, this would mean military action by the colonies themselves.4

This set of instructions stirred Virginia’s lieutenant governor Robert Dinwiddie into action by the beginning of 1754. He saw the immediate need for a military response to France’s aggressive program of fort construction in the Ohio region, as well as its influence among the Indians there. Governor Dinwiddie ordered the deployment of a regiment of Virginia provincial soldiers to the western frontier, commanded by a young, ambitious militia officer named George Washington. Lieutenant Colonel Washington had planned to supervise construction of the Virginia fort at the Forks. When his men were prevented from doing so by the French in April, he instead strengthened the stockade built by Maryland provincial troops on a hill on the north bank of the Potomac River at Wills Creek. He named it Fort Cumberland, which today is the city of Cumberland, Maryland.

Fort Duquesne, built by the French in 1754 in western Pennsylvania to control the Ohio River Valley. The Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

About seventy miles southeast of the Forks of the Ohio, Washington built at the Great Meadows a circular log palisade, which he named Fort Necessity. He garrisoned this hastily constructed post with provincial troops recruited for frontier duty, the Virginia Regiment. It was joined by an independent company of British regulars from South Carolina. Washington and Dinwiddie hoped to receive reinforcements and additional supplies from other American colonies in their efforts to control the strategic river junction and defend the backcountry from hostile Indians and French troops.

In January 1754, Dinwiddie sent a circular letter to his fellow colonial governors in Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, New York, New Jersey, Maryland, North Carolina and South Carolina, asking for soldiers, supplies and money “to defeat the designs of the French.”5 Virginia’s hopes for intercolonial cooperation went largely unfulfilled, however, as only North Carolina responded to Virginia’s plea for assistance. By the 1750s, the various North American colonies were not a united collection of governments bound by mutual interests. Most of the colonies were rivals with one another in terms of trade, culture, religion and land acquisition, and many were more closely aligned to Great Britain than to their fellow American provinces. An attempt to create a cooperative union of the colonies at a meeting of their representatives in Albany, New York in 1754 failed in the face of opposition, mistrust or disinterest. Thus, when Dinwiddie called on other colonies to assist Virginia’s efforts to expel the French from the Ohio Valley, most were disinclined to help in what they saw as Virginia’s attempt to obtain valuable lands and lucrative trade for its own commercial interests, not for the good of the British Empire.

Given North Carolina’s weak political and economic situation in the prewar years, the colony’s contribution to Virginia’s military enterprise is surprising. Up to the French and Indian War (and long after it), North Carolina had a well-deserved reputation as a poor, contentious and politically divided colony. With few good harbors for large ocean-going ships, the province was economically limited and dependent on Virginia and South Carolina for access to commercial markets. North Carolina had also seen several internal rebellions and devastating Indian wars over the previous decades. Internal political divisions often prevented effective government. Factions developed over the years that created conflicts between the eastern counties and the backcountry and between Albemarle Sound planters and their Cape Fear counterparts. The backcountry was also known as a lawless region populated by people of questionable character, loose morals and little interest in being taxed, governed or recruited for military duty.6

Despite this history, Nathaniel Rice, president of North Carolina’s colonial council (the governor’s appointed advisors) after the death of Governor Gabriel Johnston in 1752, noted that “the Country enjoys great quietness, and is in a flourishing condition, the western parts settling very fast, & much shipping frequenting our rivers.”7 Another observer, however, saw the colony on the eve of war differently. Moravian religious leader August Gottlieb Spangenberg wrote that some of the colonists were “naturally indolent and sluggish. Others have come here from England, Scotland, & from the Northern Colonies[,] some have settled here on account of poverty as they wished to own land & were too poor to buy in Pennsylvania or New Jersey.” The minister also reported that other Carolinians were “refugees from justice or have fled from debt; or have left a wife & children elsewhere,—or possibly to escape the penalty of some other crime; under the impression that they could remain here unmolested & with impunity.” He also saw that “bands of horse thieves have been infesting portions of the State & pursuing their nefarious calling a long time,” which was “the reason North Carolina has such an unenviable reputation among the neighbouring provinces.”8

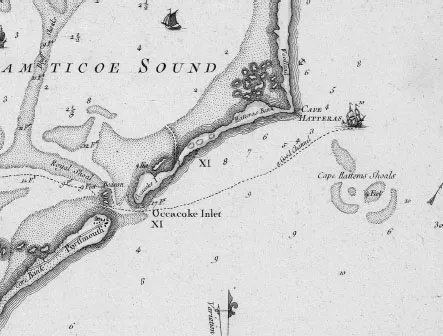

Upon the death of council president Rice in January 1753, Matthew Rowan of Brunswick County became president of the council (in effect, acting governor until one could be appointed by King George II). He and other Carolina officials began to prepare for the possibility of war with France in the American wilderness, given the news of French activities on the Ohio River and warnings from London. In late May, the North Carolina Assembly (the colony’s legislative body, often called the “lower house”) enacted a law to erect a fortification on the Outer Banks at Ocracoke Inlet, between Core Banks and Ocracoke Island, to prevent French maritime raids on the colony’s coastal port towns.9 Rowan and his council also tried to refurbish the colony’s militia organization, which in the preceding years “had been very much neglected.” He was pleased to report in particular that in the far western frontier counties of Anson, Orange and Rowan, “there is now at least three thousand [men,] for the most part Irish Protestants and Germans and dayley increasing” available for militia service.10

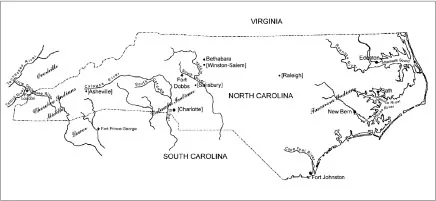

North Carolina during the French and Indian War (western border is modern). Map from Maass, “‘All This Poor Province Could Do.’”

Detail of postwar map showing Ocracoke and the new town of Portsmouth, fortified during the war. North Carolina Collection, Wilson Library, UNC–Chapel Hill.

...Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1. The War Begins

- 2. The Colony Fights an Imperial War

- 3. Turning Point: 1757

- 4. Struggle in the Wilderness

- 5. The Cherokee War

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Bibliography

- About the Author