![]()

CHAPTER ONE

THE SALOON YEARS

We learned our social and political fundamentals bellied up to the bar. I cannot recall that we ever got drunk, but upon occasion we were moderately stimulated and inspired to create and announce improvements in government, or denounce social inequities.

—Seattle newspaper reporter Jim Marshall, recalling local saloon culture during the 1880s

That Prohibition was an indictment against alcohol is, in many ways, a popular misconception. More specifically, it was a legal retaliation against the places where alcohol was served. Saloons, as they were known, had grown to become the social bogeymen of their time and would eventually be the driving force for America going dry under the Eighteenth Amendment. The starting point for all this goes back to the years immediately following the Civil War when a huge wave of German immigrants began settling here in America. These German newcomers brought with them their love of beer and soon began establishing traditional breweries that bore the Germanic surnames of their respective founders: Anheuser, Pabst, Schlitz.... Attempting to re-create the crisp lagers from their homeland, most of these breweries combined native brewing techniques with local ingredients to create a distinctly American beer that quickly became a hit with the working class. In Seattle, Andrew Hemrich established his own brewing empire, eventually founding the Seattle Brewing & Malting Company that would go on to produce the city’s most iconic beer, Rainier.

In an attempt to increase sales, many of these big breweries began setting up drinking establishments where the public could gather and enjoy their product, similar to the beer halls and brewpubs of their homeland. These German beer parlors colloquially became known as saloons, as that was already a popular term in use to describe a drinking establishment. To help entice new customers, free food was typically offered, such as cold cuts, pretzels and smoked fish. This certainly helped boost their popularity amongst the working class. By the late 1800s, beer saloons had become increasingly popular in urban areas throughout Washington State. They offered a place where men could gather to eat, drink and discuss daily affairs. Voting and banking services were commonly offered, providing a place where customers could cash their paychecks or cast votes in local elections. Overall, they were fairly honorable and respectable places where drunken behavior was relatively uncommon in favor of civil discourse and the slow imbibing of lager. These saloons provided a meeting place where one could find fellowship and good conversation, and where beer was more of a social lubricant than an intoxicant. A Seattle newspaper article at the time described the saloon as “a place where all men were equal and every man was a king.”

The majority of Washington State saloons at this time were located almost exclusively in urban areas such as Seattle, Olympia, Tacoma and Spokane. There were a few reasons for this. For one, saloons were typically owned and controlled by nearby breweries, as it ensured a location where only their beer would be sold. This type of arrangement, similar to the “two-tiered” systems found in Great Britain, helped breweries control the local market, which, in turn, allowed them to control the price of their beer. Thus, the more saloons that a brewery owned, the more of its beer that could be sold. From a logistical standpoint, though, breweries were quite limited in how far they could transport their product. Beer was not being pasteurized at this time, meaning it had a short shelf life and needed to be consumed quickly. Breweries also relied on horse-drawn beer wagons to deliver their product, limiting their delivery range to nearby streets and roadways. This kept saloons geographically anchored to their respective breweries and, as a result, they were seldom found outside of large metropolitan areas.

By the time Washington attained statehood in 1889, the nature and scope of saloons were beginning to change. The advent of transcontinental railroads allowed various items to be transported farther than ever before, and the Anheuser Brewery, in St. Louis, had recently patented the refrigerated boxcar, allowing perishable items to be transported across the entire country with relative ease. Breweries were also beginning to pasteurize their beer, allowing for a much longer shelf life. Adding to all this, crown bottle caps, which allowed beer to be sealed in individual bottles, were introduced in 1892. All these innovations now meant that large quantities of beer could be safely delivered to areas outside of a brewery’s immediate vicinity. In Washington State, companies such as the Great Northern Railway and Northern Pacific were in fierce competition with one another and, within a relatively short period of time, newly built railroad lines that crisscrossed the state opened up easy and affordable commerce between urban and rural locations. This included the transfer of beer and alcohol. Brewers certainly took notice of this and began setting up saloons along railroad routes in order to increase their market share. In the span of just one year—between 1889 and 1890—Washington State beer sales increased by 33 percent, a direct result of these new railway routes.

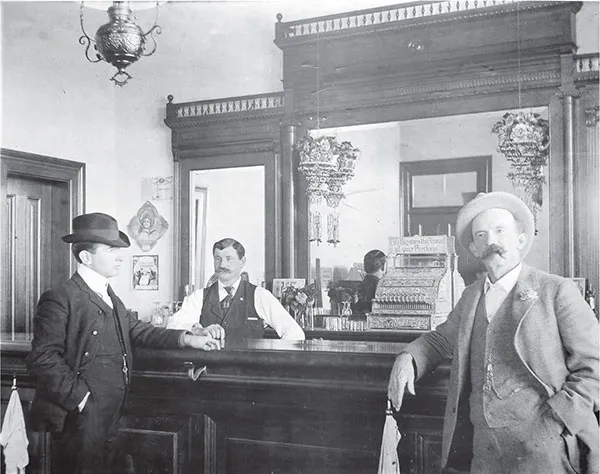

Seattle saloon, circa 1890s. Author’s collection.

As a result of all this, saloons began proliferating across the rural landscape at a dramatic rate. Unlike their urban counterparts, however, these smaller towns lacked the social infrastructure and evolved cultural nuances to properly handle such drinking establishments. Whereas the urban brewpub served as a civil gathering spot for enlightened conversation, rural saloons almost immediately established themselves as rowdy destinations where intoxication, violence and disorderly conduct disrupted the tranquility of small-town living. They were places where men went to drink and brawl and, amongst these bucolic communities, the whole thing felt like an immoral invasion. Stories emerged of families thrown into poverty and neglect due to the men spending all their time and money at the saloon. Rates of domestic violence and alcohol-related arrests spiked up, as did the rates of divorce. This followed national trends associated with the proliferation of saloons and the unintended social problems that accompanied them.

Rainier Beer delivery wagon, late 1890s. Author’s collection.

Tacoma saloon, circa 1890s. Author’s collection.

While saloons spiraled out of control throughout rural Washington, the once gentle nature of Seattle’s beer joints also began to transform. Major events, like the Yukon Gold Rush of 1896, had attracted thousands of people to the city, and local vice syndicates were happy to help satisfy their needs. No longer just controlled by local breweries, a new generation of saloonkeepers and parlor house owners emerged who were eager to cash in on all the gold rush money (“mining the miners,” as the catchphrase became known). Before long, saloons, cigar stores, gambling parlors, dance halls and brothels popped up all across the city, most of them located south of Yesler Way in an area that became known as the Tenderloin District. A large population of “seamstresses” suddenly began advertising their services in the Tenderloin and, while nobody ever witnessed any actual sewing, the boardinghouses where they lived sported telltale red lights.

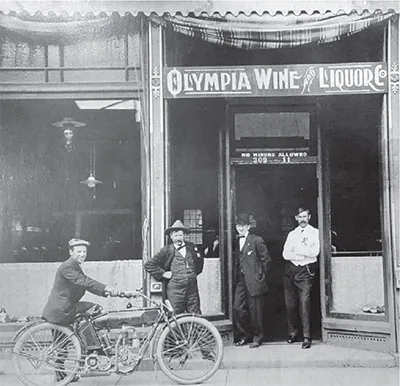

Olympia Wine & Liquor Co. in Olympia, Washington, circa 1910s. Author’s collection.

This neighborhood, which had already earned a notorious reputation well before the gold rush days, was now becoming even more dissolute. At any given time, the streets would be crowded with men looking for a good time. Lou Graham and other parlor house owners would parade their girls up and down the streets on ornately decorated carriages. Barkers would stand outside the doors of saloons and loudly try to entice new customers into their establishments amid the excited clatter of nearby gambling halls, billiard parlors and the all too frequent street fight. Adding to the adventurous excitement, there was also the constant threat of being shanghaied, in which men were drugged and rendered unconscious (usually in the setting of a saloon), and would then have their signatures forged on papers that committed them to compulsory service aboard a ship. The next morning, the man would wake up from his stupor and find himself as an enslaved crewman aboard some unknown ship bound for a foreign port. During the gold rush days, shanghaied sailors would usually find themselves on ships headed for Alaska. It was so prevalent, in fact, that the Seattle Star warned its readers that shanghaiing was being practiced in the vice district to “an alarming extent.” The Tenderloin ran twenty-four hours a day, though nights were particularly rowdy. One newspaper account at the time summarized the scene as “sin, vice and crime sneak forth like human wolves only after the sun goes down.”

From this, a new type of institution evolved in which all forms of vice blended together and became available at one convenient location. Boxhouses, as they became known, were saloons which also offered gambling, narcotics and prostitution. Typically, a stage was set up in which female dancers (in an early version of burlesque) would dance and perform in a suggestive manner for the entertainment of those inside. If the male patrons liked what they saw, there were private cubicles, or “boxes,” along the walls in which certain other transactions could be negotiated. Many of these rooms contained a single couch or small bed which, according to local religious leaders at the time, permitted “immorality in its most depraved form.” One popular boxhouse, located on an Elliot Bay pier, was known for having trapdoors hidden in the floor. If a customer became too drunk or belligerent the saloonkeeper would simply pull a lever, sending the person plunging into the cold Puget Sound waters below.

The so-called king of these boxhouses was a man by the name of John Considine. Considine himself was a teetotaler but operated his saloons with a tenacious business sense, controlling much of the city’s gambling, drinking and prostitution revenue. He used the People’s Theatre, one of the city’s largest boxhouses, as his headquarters. So strong was his grip on the local underworld that he famously chased notorious gunslinger Wyatt Earp out of town. Like many others before him, Earp had attempted to cash in on all the Alaskan Gold Rush money flowing into the city by setting up the Union Club—a saloon and gambling parlor—in the heart of Seattle’s vice district. Considine took notice of this new competition and personally advised Earp to leave. The famous gunslinger not only disregarded this advice but used his celebrity status to establish the Union Club as one of the city’s most popular saloons. Fed up, Considine made use of his local political connections, and on March 23, 1900, criminal charges were filed against Earp and his business partners. The club’s furnishings were confiscated and burned and Earp was essentially chased out of town. Despite his battles with the famous gunslinger, Considine formed symbiotic partnerships with other saloon owners. This included the notorious William Belond, who operated the popular saloon Billy’s Mug at First and Washington. Billy the Mug, as he was commonly known, had a reputation for being one of the toughest saloon owners in Seattle and was well known for grabbing rowdy customers by the scruff of the neck and forcibly throwing them through the front door and out onto the street. His saloon certainly reflected his own roughhouse character as he frequently hosted cockfights and pit bull fights with his bar packed full of loud and drunk customers shouting out their bets. Billy’s boasted a fifty-foot-long bar where skilled barkeeps such as Herman Butzke, the famous singing bartender, would expertly slide mugs of beer down the narrow bar and precisely land them in front of customers. For a mere nickel, Billy’s Mug offered a “quart and a gill” (essentially two and a half pints of beer), with a free schooner given to whoever could down it in one breath. Considine negotiated a deal with Billy in which he operated the rooms above the saloon to serve as a gambling joint known as the Owl Club. Considine’s vice empire was growing by the month, and his boxhouses were known for having the most beautiful and entertaining stage performers, including the then-famous belly dancer, Little Egypt.

In 1901, Considine had a falling-out with Seattle police chief William Meredith. The feud between the two men escalated, resulting in a very public war of words and, eventually, a shoot-out at a downtown drugstore. In the violent melee that followed, Meredith was fatally gunned down and Considine arrested. Later acquitted of the subsequent murder charges on grounds of self-defense, Considine would decide to go “legit,” using his boxhouse experience to help cofound a new, successful form of entertainment that would eventually become known as vaudeville.

Seattle boxhouse lord and vaudeville impresario John Considine, 1908. Courtesy of Museum of History and Industry (MOHAI).

William Belond, otherwise known as rowdy saloon owner Billy the Mug, 1897. Courtesy of Museum of History and Industry (MOHAI).

It didn’t take long for a moral backlash to begin forming against all this. For many local religious groups, the levels of vice in Seattle and the proliferation of saloons throughout the state had become too much and immediate action needed to be taken. In the Midwest, groups such as the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) and the Prohibition Party had become powerful social and political forces intent on shutting down these troublesome establishments and bringing temperance to the masses. This anti-saloon sentiment soon spread throughout Washington, representing a larger and broader attitude that would soon engulf both local and national elections.

![]()

CHAPTER TWO

THE PREACHER AND THE MAYOR

The saloon is the most fiendish, corrupt, hell-soaked institution that ever crawled out of the slime of the eternal pit....It takes your sweet innocent daughter, robs her of her virtue, and transforms her into a brazen, wanton harlot.... It is the open sore of the land!

—Reverend Mark A. Matthews of the Seattle Presbyterian Church

Of all of Seattle’s mayors, none have had a more controversial tenure than that of Hiram Gill. Arriving in Seattle as a brash, young attorney in 1892, Gill was able to recognize an unfilled niche amongst the vice-filled city and soon established a thriving legal practice defending saloonkeepers and brothel owners. His business proved to be a success, but Gill had loftier ambitions than keeping saloon owners out of jail. In 1898, he was elected to the Seattle City Council, serving on and off as a Republican candidate until 1910. His peculiar looks and controversial past made him a favorite target with the local media, with one reporter describing him as having “a pinched triangular face, a nervous, twitching mouth and keen but shifty blue eyes.” During this time, as vice spread across the city, Seattle politics became divided between “Open Town” and “Closed Town” factions. Open Town proponents believed that alcohol, prostitution and gambling were normal human activities and should be permitted as long as they were regulated and restricted to a certain part of the town. Closed Town advocates, including local clergy and temperance leaders, lobbied that no such conduct should be permitted at all and should be aggressively enforced.

One of the most prominent figures on the Closed Town side was local Presbyterian minister Mark A. Matthews. Known as the “black-maned lion” du...