![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Louisiana and Mississippi in the Colonial Period

In the mid-eighteenth century, the Mississippi River delta, which stretches from present-day New Orleans, Louisiana, to Vicksburg, Mississippi, was sparsely populated. Yet the people who came to the bayou were already diverse in origin, purpose and lifestyle. French traders scouted the wilderness for new settlements, while Spanish explorers moved eastward from New Spain in search of new colonial prospects. Meanwhile, Choctaw Indians, displaced by Europeans who were settling along the East Coast, had moved into the area around the mouth of the river. The region was poised for change, and no corner of the Mississippi River valley was more a crucible of that change than New Orleans.

The first documented Jewish settler arrived in this region, specifically in New Orleans, in 1757. Various land grants, newspapers, letters and legal records from this period serve as trace evidence of other Jewish persons who passed through the area. However, these indicators are based largely on assumption. The Caribbean world at this time was well populated with Jewish entrepreneurs who had planted roots in the tolerant Dutch colonies of Suriname and Curaçao, as well as British Jamaica and Barbados. These entrepreneurs often traveled from market to market, heading to wherever trade was most favorable at the time. In 1685, the French Crown issued a decree called the Code Noir, an edict that primarily regulated commercial and religious standards regarding the African slave trade. However, the edict’s first three clauses included provisions for the exclusion of Jews and Protestants from all of France’s American colonies, and that included Louisiana. The Code Noir was revised several times over the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, although the most significant revision took place in 1724. Thus, while some Jews from the Caribbean and elsewhere may have traveled to Louisiana, their identity as Jews would have had to remain secret.

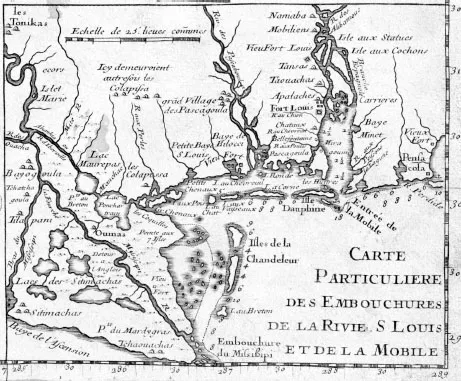

French Louisiana during the colonial period before the founding of New Orleans, circa 1718. Library of Congress Geography and Map Division.

As the slave trade expanded in Louisiana, the question of the conversion of slaves was foremost in the mind of colonial administrators and missionaries. According to the Code Noir, slaves must be baptized as Roman Catholics, and the presence of non-Catholic slave owners threatened colonial leaders with the possibility of slaves becoming Protestants. Louisiana was also a proprietary colony, in which commerce was strictly controlled, and even religious policy was focused on maintaining that control. It is likely that the exclusion of non-Catholics from the territory was meant to remove commercial competition, be it from French Huguenot traders, Dutch Jewish merchants or British Anglican privateers.

While the Code Noir banned Jews in the colonies, it is widely accepted among scholars that the prohibition was preemptive, as no record exists of Jews who may have been active in Louisiana before 1724. Additionally, the colony was not prosperous enough at the time to draw much competition. It was not until later in the eighteenth century that economic factors shifted attention toward New Orleans. Even at that point, the French administration in Louisiana did not strictly enforce the regulations of the Code Noir, often turning a blind eye to the portion of the code pertaining to Jews. In fact, Isaac Monsanto became one of the most prosperous Jewish merchants in French New Orleans, often dealing with high-ranking figures like Chevalier Louis Billouart de Kerlerec, Louisiana’s colonial governor.

Isaac Monsanto arrived in New Orleans in 1757 and quickly established a residence before gradually relocating his family to the city. His place in the mercantile economy of the New World is representative of the great network of trade forces present at the time. Having moved with his family as a young man from the Netherlands to Curaçao, he and his brothers engaged in transporting goods between French Saint-Domingue, British Jamaica, Spanish Cuba and the mainland colonies in North America. New Orleans factored heavily into his Caribbean business interests. In fact, it was in New Orleans’s courts that Isaac and his business partners fought for restitution after British privateers seized a ship carrying cargo that belonged to him. This incident not only prompted Isaac to relocate to New Orleans, but it is also indicative of the city’s burgeoning business landscape and the role Jews had in developing its trade relationships. By the time Isaac settled in Louisiana, he had already exchanged goods with coreligionists in Rhode Island and elsewhere. Isaac’s brothers and sisters followed him to Louisiana soon afterward.

Isaac Monsanto and his siblings may have been the first to become established in New Orleans, but it is possible that other Jewish individuals and families of various origins moved to the city within the next decade. While Isaac developed his trade empire, correspondence between colonial officials suggests other Jewish businesses had developed in and around the city as well. By 1769, Louisiana had roughly 14,000 colonists, 3,500 of whom resided in New Orleans. Although the exact number of Jews who occupied the area during this period is not known, they definitely made up a small portion of the population, possibly fewer than one dozen people.

During the 1760s, France fought against Britain in the Seven Years’ War, known in the New World as the French and Indian War. This war was waged on a large scale, which interfered with the bustling mercantile trade between the Americas and Europe. For the growing Crescent City, this meant obstruction of regular commerce, which forced the city into an economy of necessity. Jews and others who had engaged in Caribbean commerce with places like Curaçao, Jamaica and Saint-Domingue saw a growing market in New Orleans—seen as the gateway to the North American interior—and moved to meet demand. Motivated by the opportunity, other Sephardic Jews immigrated to Louisiana in the early 1760s. Isaac himself entered into the New Orleans scene with two partners, Manuel de Britto and Isaac Henriques Fastio, who had joined him from Curaçao. Other Jews who may have lived elsewhere but engaged in business in Louisiana were David Mendes France, Samuel Israel, Joseph Palacios and Alexander Solomons. While the Jewish population in New Orleans remained small throughout the 1760s, its members were significant figures in the colonial economy.

The Monsanto family—Isaac, his brothers Manuel, Benjamin and Jacob and his sisters Angélica, Eleanora and Gracia—was tightknit by any definition of the term. They often cohabitated in New Orleans, as well as in other residences they established over the years; numerous correspondences between the Monsantos show how affectionate and cooperative they were to each other despite the obstacles of distance and adversity. Isaac, considered the founder of the family’s legacy, was by all accounts a shrewd businessman, often engaging in banking as well as his trading ventures. In 1766, he lived on Chartres Street in the present-day Vieux Carré (French Quarter) of New Orleans. Chartres Street would later become a Jewish business district in the early nineteenth century. In 1767, Isaac purchased a plantation known as Trianon outside the city limits. His success was widespread and shared by other members of his family. By the time the family was forced to leave Louisiana in 1769, Isaac Monsanto was among the city’s wealthiest merchants.

The end of the French and Indian War caused a territorial shift that drastically altered the colonial landscape. The war had primarily been between France and Great Britain, but alliances between France and Spain had caused the Spanish to invest heavily in aid to France. With the close of the war and the Treaty of Paris in 1763, France relinquished its Louisiana colony to Spain, including the entire lower Mississippi territory. In turn, Spain, which had held territory in Florida and a long stretch of land along the Gulf Coast that extended into present-day Louisiana, ceded much of its holdings to Great Britain. All territory south of the thirty-first parallel remained in Spain’s possession, and some of the holdings included the fort at Nogales, once known as the French Fort Saint-Pierre, and what would become Vicksburg, Mississippi. Thus, present-day Mississippi was divided between Spain and Great Britain, and Louisiana came under the Spanish crown.

Louisiana’s transfer to Spanish control caused unease among the few Jews living in the territory, the Monsantos included. The local French colonial government’s lax enforcement of the Code Noir had allowed these Jewish merchants and storekeepers to settle in the area, but the Spanish were much more restrictive in their economic and religious interests. The arrival of the second Spanish governor, Alejandro O’Reilly, brought the harsh reality of Spanish rule to Louisiana. Not long after his arrival, he expelled all Jews from the colony.

But O’Reilly’s decree of expulsion was not limited to Jews; he banished all foreigners from Spanish Louisiana. This included all non-Catholics and even some French merchants in New Orleans. Jews were not welcomed in Spanish territory even before Spain’s takeover of the colony. In 1492, Spain’s King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella decreed that Jews were prohibited from Spain and its viceroyalties.

The fact that Isaac Monsanto was a Jew may not have been as relevant to the decree as was his fortune, property and overall success. Jews in New Orleans and colonial outposts who weren’t economic threats to the Spanish monopoly were left alone. Isaac Fastio, who had moved to the trade settlement of Point Coupee shortly after his arrival with the Monsantos in 1757, was permitted to remain, as were other less successful Jews. Marc Eliche, an Alsatian Jew, established a small trading post roughly fifty miles north of Baton Rouge in 1794 and operated it under the Spanish colonial presence without harassment. Regardless of the motivation for the expulsion, though, Isaac Monsanto was stripped of most of his property, including his plantation at Trianon, and made to leave with little remnants of his once great fortune.

The Monsanto family left New Orleans in 1769 and dispersed in search of stability. Manuel Monsanto may have traveled north within the colony toward Natchitoches, although he did not arrive there. Some sources speculate that he may have partnered with Isaac Monsanto’s colleague, John Fitzpatrick, in the town of Manchac near Lake Pontchartrain in British territory. Benjamin and Jacob Monsanto also joined their brother in this venture. In the years following their expulsion and until Isaac’s death in 1778, the Monsanto brothers frequently moved between the towns of Manchac and Point Coupee.

The undeniable resourcefulness of the Monsanto family is only one example of a greater trend among Jews who were involved in the Caribbean trade. These merchants had developed a culture of trade so wide and successful that historians have recognized it as an integral part of the economy of this period. Their commercial activities provided an indispensable source of American and European goods. Even in a hostile climate, the Monsanto brothers engaged in vital entrepreneurialism that foreshadowed the economic future of Jews in the Mississippi region.

The Monsanto sisters settled in Pensacola, then part of British West Florida. Over the next few years, all three sisters married non-Jewish men. Eleanora moved to Saint-Domingue, where she married Pierre André Tessier de Villauchamps. She would soon return to Louisiana and join her brother Manuel in 1775. Gracia married Thomas Topham and was also later reunited with her brothers. Angélica Monsanto married George Urquhart, an active leader in the West Florida colony, and the couple also moved to Manchac for a time before Urquhart’s death in 1779. Spanish forces captured Manchac during the American Revolution, and this disruption likely ended the Monsantos’ activity in the town.

Isaac Monsanto died at Point Coupee in 1778 and never regained the wealth he had known while living in New Orleans, but he continued his entrepreneurial pursuits. Until his death, Isaac repeatedly visited New Orleans and other towns in Louisiana territory with little consequence. It seems that once the Monsanto family was eliminated as an economic power in New Orleans, the Spanish authorities had little interest in their presence.

After the death of her husband, Angélica returned to New Orleans to be near her brothers, who had moved back to the Crescent City and were continuing to manage the family business. She eventually married again, this time taking Dr. Robert Dow, a Protestant physician who was prominent in New Orleans philanthropic circles, as her husband. After marrying Dow, Angélica became a devout Protestant. She remained in New Orleans for the rest of her life, even when her new husband wished to escape the oppressive weather of the city and return to Europe. After she died in 1821, he returned to Scotland. Angélica was interred at New Orleans’s Protestant Girod Street Cemetery.

Benjamin, Manuel and Jacob Monsanto continued to manage their mercantile firm and primarily dealt in land, commodities, dry goods, debt collection and slaves. Documentation shows that the three brothers and Isaac, before his death, made many small and a few large transactions in selling slaves, including a 1785 exchange in which Benjamin traded thirteen slaves for roughly three thousand pounds of indigo. Most merchants at that time engaged in slave trade as part of a wider range of interests. The Monsanto brothers did rather well in slave trading, as well as other areas. They purchased items that could be marketed in New Orleans and rural outposts, including liquor, clothes, silverware, lumber, fabric, tea, tobacco, soap, animal skins and horses.

By the 1780s and 1790s, Manuel and Jacob Monsanto had relocated to Toulouse Street in New Orleans. Benjamin, however, moved to Natchez with his wife, Clara, and their children and operated part of the family’s affairs from there. He also established a plantation in Natchez by 1785. Then known as the Natchez District, the town was in the process of becoming a commercial hub. It was also strategically located on a high bluff on the eastern bank of the Mississippi River, and because other trade settlements like Manchac and Point Coupee had begun to decline, colonial powers fought over control of the district. By the time Benjamin Monsanto established his plantation along St. Catherine’s Creek in Natchez, the town had become Spanish territory.

Although growing, Natchez was still small, with only about one thousand residents and very few merchants. Most early settlers in Natchez were, like Benjamin Monsanto, planters and farmers. Undoubtedly, the town proved to be an ideal market for the Monsanto brothers’ partnership, and the townspeople held Benjamin in high esteem. His language skills in English, Spanish and French made him an asset in this transforming settlement. In an oft-quoted letter from Major Samuel Forman dated circa 1790, the major indicates that the Monsantos not only found it unnecessary to conceal their religion in the Spanish city but also enjoyed some personal notoriety in the town: “In the village of Natchez resided Monsieur and Madam Mansanteo [sic]—Spanish Jews, I think—who were the most kind and hospitable of people.” Yet life as a planter did not seem to bring Benjamin much success. Evidence shows that his plantation venture was eating into his mercantile business shortly before his death.

By the 1790s, the Mississippi region was still a politically and socially volatile area. The early settlers found themselves sandwiched between the new United States and the Spanish Empire, which continued to dispute ownership of the territory, as well as vie for commercial use of the river system. Anticipation of opportunity and profit in the new American frontier spurred population shifts westward that would continue into the nineteenth century. The development of the Natchez Trace as a trade route spurred the growth of new towns along its path, including the settlement of Port Gibson. New Orleans continued to grow in population as well.

The manner through which the Monsantos and others expressed their Jewish heritage is difficult to ascertain. It is clear that while the Monsanto siblings were raised by practicing Jewish parents in the Netherlands, their assimilation into French and Spanish Louisiana societies left little freedom to engage in an established Jewish community. Even in private homes, there is no evidence of a Jewish congregation in the Mississippi region in the colonial period. Although life under French and Spanish rule had been relatively permissive regarding the religious backgrounds of its colonists, the practice of any religion outside the Roman Catholic Church was not well received in Louisiana. This social norm was so ensconced in colonial life in the area that Benjamin Monsanto likely had no other choice but to marry his wife, Clara, in St. Louis Cathedral, which he did in 1787. Indeed, marriage within a church was a common practice amongst crypto-Jews who resided in Spanish lands. However, with the exception of Angélica Monsanto Dow, none of these early pioneers converted. Converting to Catholicism would have prevented Isaac Monsanto’s exile from the colony, but it is apparent that, although conversion was an option for members of the Monsanto family, no brother or sister was willing to deny their heritage. These Jews of the eighteenth century were part of a dynamic colonial world that rewarded adaptation and intuition. That they were secularists for the most part is not surprising, and their legacy carried on into the turn of the century, when many more like them arrived in the lower Mississippi River valley. To a greater extent, these non-practicing Jews and those who would soon follow were the norm rather than the exception. Overwhelming evidence suggests that, until the second quarter of the nineteenth century, “there were Jews in Louisiana, [but] there was no Judaism.”

During the colonial period, New Orleans served as a gate city to an enormous frontier. It was also the principal port for all commerce along the Mississippi River and interior territories. Spanish rule had restricted aspects of trade occurring in the city but could not completely bridle the aspirations of merchants, planters, investors and even pirates. An elite Creole class had already developed in the city itself, and this class would guide political development within New Orleans over the next century. For the most part, members of this class were restless under the Spanish crown. The desires of this elite class, along with the desires of Napoleon Bonaparte, led to the return of French rule to the territory in 1800. This second French period hardly lasted three years, and the colonists themselves knew only by rumor that they were again under French rule. The territory was once again transferred in 1803, but this time, it would come under the control of the United States.

![]()

CHAPTER TWO

Antebellum New Orleans and the Civil War

At the time of the Louisiana Purchase, New Orleans was a rapidly growing city composed of numerous cultures and languages. Spanish rule had encouraged settlers from Mexico and Cuba to move into the area. French Acadians who had been expelled from British Canada migrated southward into Louisiana territory, where they would eventually become the ethnic group known as the Cajuns. Colonists from British West Florida also moved into New Orleans, as well as other towns that bordered the Mississippi River. Additionally, Native Americans from various tribes came to the city to trade. Migration from the United States westward accounted for a great deal of this population shift as well; many of the first Jews to arrive in New Orleans at the beginning of the nineteenth century had, in fact, been born as Americans. By 1800, New Orleans’s population had increased to roughly ten thousand and would increase tenfold by 1860.

Joining the mostly Sephardic Jewish immigrants who had arrived in this early period were Central European Jews, many of whom were Bavarian and Alsatian. Some of these newcomers likely left Europe for personal reasons, but there were broader migration trends among Ashkenazic Jews already at work by 1803. In the wake of the Napoleonic Wars, the quality of life for Jews in Central Europe was miserably restrictive. Quotas were placed on the Jewish community regarding property, marriage and even the number of children a Jewish family could have. The prospect of life in the new United States was attractive to many, and as letters came in from Ashkenazic Jews who had relocated to the New World, more and more individuals and families made the trip overseas. Over the course of the nineteenth century, the Jewish community in New Orleans would develop significantly.

Bird’s-eye view of New Orleans by John Bachmann. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs.

The small group of Jews who were active in New Orleans in the first de...