eBook - ePub

Civil War Legacy in the Shenandoah

Remembrance, Reunion & Reconciliation

- 160 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This regional history examines the process of mourning and reconciliation for the people of Virginia's Shenandoah Valley in the aftermath of the Civil War.

After four bloody years of Civil War battles, the inhabitants of the Shenandoah Valley needed to muster the strength to recover, rebuild and reconcile. Most residents had supported the Confederate cause, and in order to heal the deep wounds of war, they would need to resolve differences with Union veterans.

Union veterans memorialized their service. Confederate veterans agreed to forgive but not forget. And each side was key to the rebuilding effort. The battlefields of the Shenandoah, where men sacrificed their lives, became places for veterans to find common ground and healing through remembrance.

In Civil War Legacy in Shenandoah, historian and professor Jonathan A. Noyalas examines the evolution of attitudes among former soldiers as the Shenandoah Valley sought to find its place in the aftermath of national tragedy.

After four bloody years of Civil War battles, the inhabitants of the Shenandoah Valley needed to muster the strength to recover, rebuild and reconcile. Most residents had supported the Confederate cause, and in order to heal the deep wounds of war, they would need to resolve differences with Union veterans.

Union veterans memorialized their service. Confederate veterans agreed to forgive but not forget. And each side was key to the rebuilding effort. The battlefields of the Shenandoah, where men sacrificed their lives, became places for veterans to find common ground and healing through remembrance.

In Civil War Legacy in Shenandoah, historian and professor Jonathan A. Noyalas examines the evolution of attitudes among former soldiers as the Shenandoah Valley sought to find its place in the aftermath of national tragedy.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Civil War Legacy in the Shenandoah by Jonathan A Noyalas in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & American Civil War History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

“RECONCILE…TO THE CONQUEROR”

Several months after the Civil War ended, John Trowbridge—a noted author of the time—toured Virginia’s battlefields. As a train carried him into Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley, he peered out his passenger car window and viewed the aggregate impact of four years of incessant campaigning, numerous battles and occupations by armies of blue and gray. “We passed through a region of country stamped all over by the devastating hell of war. For miles not a fence or cultivated field was visible,” Trowbridge observed.11 As Trowbridge gazed at the passing landscape, a resident of Winchester who was sitting next to him informed Trowbridge: “It is just like this all the way up the Shenandoah Valley…The wealthiest people with us are now the poorest. With hundreds of acres they can’t raise a dollar.”12 A correspondent for the New York Herald who visited the valley shortly after the war ended echoed Trowbridge’s assessment of the region’s appearance: “Between Harpers Ferry and Staunton, a distance of one hundred and thirty miles, they have been devastated almost as thoroughly as the valley of the Elbe from the thirty years’ war of Germany.”13

The scene of desolation in the Shenandoah Valley shocked Confederate veterans as they looked at the communities and farms so terribly devastated by the conflict. For Confederate veteran Robert T. Barton, his native Frederick County in the lower (northern) Shenandoah Valley appeared a barren wasteland in the spring of 1865. Barton explained in his postwar memoir: “The fences and woods were wholly destroyed, the stock and farming implements all gone, no crops in the ground, many of the houses and barns destroyed or decrepit from long want of repairs.”14 When Confederate cavalryman John Opie returned, the destruction in the valley shocked him. He described the scene simply: “This Valley, which once blossomed as a flower garden, was one scene of desolation and ruin.”15

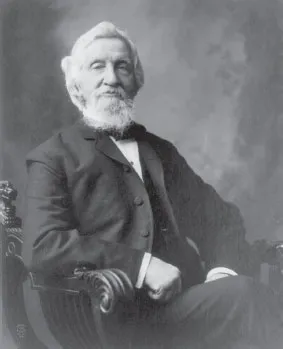

Author John T. Trowbridge. Library of Congress.

To valley residents—a people who, before the war, produced nearly 20 percent of Virginia’s wheat and hay crops and almost 30 percent of the Old Dominion’s rye crops—the region’s economy and lifestyle seemed ruined.16 Although the livelihoods of so many valley families appeared destroyed, what had not been broken was their resolve to rebuild and rise as quickly as possible from the ashes. As early as August 1866, area newspapers reported that many of the mills destroyed during the conflict had been either rebuilt or repaired and stood ready to grind wheat.17 Although the Shenandoah Valley had a long way to go on its path to recovery, it made significant strides within one year after the conflict’s end.

A visitor to the Shenandoah Valley the following spring seemed inspired by the unbreakable spirit of the region’s inhabitants. “It is wonderful, truly wonderful, how the people of this beautiful Shenandoah Valley have rallied from the prostration of war,” noted a New York correspondent in May 1867. The journalist continued in awe: “But, without fences to their fields in numerous cases, these Virginians have raised their annual crops, and without fences still to a great extent, there is a good prospect that they will have the largest wheat crop this year that was ever known here, the whole length of the valley, and indeed throughout the States.”18

Visitors who focused on the recovery of the region’s farms and mills saw progress, but when those same individuals entered the region’s towns and cities, they noticed an interesting dichotomy. While the Shenandoah Valley’s landscape appeared to be physically on the mend due to the hard work of farmers and laborers, the valley’s inhabitants—although determined to rebuild—still publicly bore the emotional scars of the conflict. The same New York newspaper correspondent who stood in awe of the valley’s physical transformation in the spring of 1867 appeared despondent at the depression exhibited by the area’s citizens. Although he observed physical recovery in Winchester, he noted that “the old time gayety of the place is gone. There is no show of fashion on the main street in the afternoon, and among the women seen abroad a fearful proportion are in somber black.”19

As this reporter from the New York Herald journeyed throughout the valley, he noticed the same dejected attitude in every community he visited. “The number of widows in this and all the other towns up to Staunton is large,” the New Yorker observed.20 When the correspondent engaged in discussions with these Confederate widows, he discovered that although the war had been over for two years, they still held a “strong secesh sentiment.”21

Nowhere was that pro-Confederate sentiment displayed more glaringly than in the Shenandoah Valley’s Confederate cemeteries. The creation of memorial graveyards to honor the Confederate dead concerned a number of northern politicians in the Civil War’s immediate wake. Some, such as Pennsylvania congressman Thomas Williams, believed that the establishment of Confederate cemeteries would allow the “strong secesh sentiment” to persist, foster disdain among future generations of southerners toward the national government and provide a seemingly insurmountable obstacle to national reconciliation. So adamant had Congressman Williams become that he proposed legislation on June 4, 1866, to prohibit any activities that honored the Confederate dead.22 Williams’s legislation did not gain momentum because a majority of Congress viewed the individuals in charge of the effort to honor the Confederate dead—women—politically irrelevant and no real threat to the Republic’s future political stability.

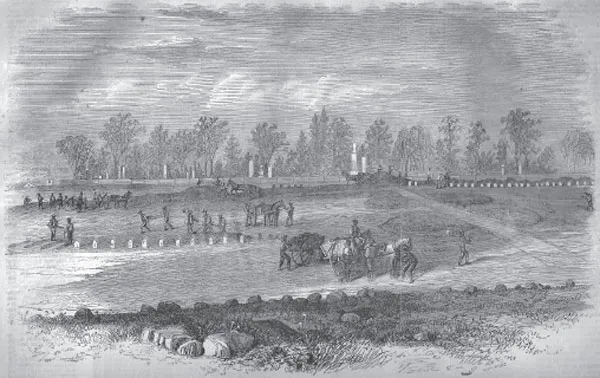

Two days after Williams offered his legislation, the Confederate Ladies’ Memorial Association of Winchester observed the first Confederate Memorial Day in the Shenandoah Valley. Held in the under-construction Stonewall Confederate Cemetery, a place identified by one former Confederate as “the Mecca of our people,” the place seemed an inspiration to not only the valley but also the entire South. Largely regarded as one of the first established Confederate cemeteries in the South, if not the first (its origins can be traced to early May 1865), the Stonewall Cemetery clearly illustrated that the defeated Confederacy might have to accept the war’s results but would not forget those who fought for the “Lost Cause.”23

Several Union soldiers who served as part of the Union occupation force that remained in the region after the conflict attended the ceremony out of curiosity. As the Union soldiers walked into the cemetery, they spied the speaker’s stand decorated with an arch. The arch bore the simple words: “To the Confederate Dead.” Beneath the arch’s center hung a dove, the symbol of peace. Beyond the arch, the cemetery bore no decorations that indicated the commemoration of Confederate Memorial Day. Those who participated in the ceremony, however, did not refuse to display Confederate symbols because they wanted to promote the Union but because they had no other choice. Although federal law did not prohibit the establishment of Confederate cemeteries, it did forbid the display of any of the Confederacy’s old symbols.24 Citizens and former Confederate veterans who participated did display a new emblem of the old Confederacy in the cemetery—a large cross of evergreens, which symbolized the blue cross that bore the white stars of the Army of Northern Virginia’s battle flag.25

Stonewall Confederate Cemetery under construction. Author’s collection.

The Union soldiers—some of whom had fought in General Philip H. Sheridan’s 1864 Shenandoah Campaign—watched intently as the first speaker, Confederate veteran Uriel Wright, walked to the podium. Those Union veterans listened carefully for any defamatory remarks against the government and, perhaps somewhat to their surprise, heard none. A visitor to that ceremony recorded of the tense moment: “The propitious moment had arrived. Many leaned forward to catch the first words of the speaker. What would he say? What could he say, were questions no doubt asked in the minds of many.” Tensions eased when Wright opened: “No potentate or power upon Earth can deprive us of the right to mourn for the dead.”26 With these words the Union soldiers seemed satisfied that this was a mere act of mourning and remembrance, not one intended to rekindle the old Confederacy. The Union soldiers left without uttering a word.27

Four months after the first Confederate Memorial Day in the Shenandoah Valley, its inhabitants prepared to formally dedicate the Stonewall Confederate Cemetery. The day of the formal dedication, October 25, 1866, began with the re-interment of four Confederate officers: Captain George Sheetz, Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Marshall, Captain Richard Ashby and Brigadier General Turner Ashby. All of these officers had been buried at other places during the conflict but were now used to further consecrate the ground at the Stonewall Cemetery.

Undoubtedly the most beloved of these Confederate officers had been General Ashby. Ashby was killed while fighting a rear guard action in Harrisonburg, Virginia, on June 6, 1862, and valley residents viewed him as the Civil War’s first tragic hero in the region. The people of Winchester manifested their devotion to Ashby when they chose his death date as the observance of Confederate Memorial Day, a date still honored in that city. As the horse-drawn hearse bore the bodies of these four Confederate officers into the cemetery, the U.S. Army officer commanding the post in Winchester, identified in the records as simply a Captain Brown, ordered the flag in the National Cemetery—separated from the Stonewall Cemetery by only a narrow lane—to be lowered to half-staff. Brown’s act proved to be the first step on the path to healing the Civil War’s wounds in the Shenandoah Valley between Union and Confederate veterans.28

An unidentified group gathers around the grave of Turner Ashby and his brother Richard following a Confederate Memorial Day service in Stonewall Confederate Cemetery. Author’s collection.

Despite this gesture, many former Confederates had tremendous difficulties in burying animosities so soon after the conflict’s end. Although challenging to quantify, evidence indicates that former Confederates in the Shenandoah Valley tried to put on a brave face but still grieved for the defeat, loss of property and, above all, the loss of loved ones. Newspapers in the valley conveyed a sense as early as the summer of 1865 that valley inhabitants “have resolved to be, in [the] future, loyal citizens of the United States.”29 That transformation would not occur immediately, however. Valley resident Kate McVicar wrote that area residents who supported the Confederacy could not “reconcile themselves to the conqueror yet, or forget the scenes they passed through,” but they would try to move forward.30 A northern visitor to the Shenandoah Valley observed: “They cannot forgive the North” for the war “in their hearts, but it is not often they allow their sentiments to overcome them.”31

In addition to a strong lingering Confederate sentiment in the area, visitors to the valley also noted that former Confederates seemed to place much of the blame for the Shenandoah’s hardships on one man: General Philip H. Sheridan. Identified by a Shenandoah Valley newspaper in 1870 as “a Ghoul and barn burning villain,” Sheridan became the focus of a hatred that still exists to this day in the Shenandoah Valley.32

Valley inhabitants targeted their anger toward Sheridan because it was during his tenure in the region that the campaign with the most widespread destruction of private property in the shortest period of time occurred—“the Burning.” While Shenandoah Valley inhabitants first suffered the consequence of war by the torch in the late spring of 1864 when Union general David Hunter marched through the region, Sheridan brought the most widespread devastation to the Shenandoah Valley in the autumn of 1864.33 In the campaign’s aftermath, Sheridan reported that his command, between late September and early October 1864, destroyed around 1,200 barns and in excess of 435,000 bushels of wheat, the valley’s staple crop, as well as seized nearly eleven thousand head of cattle.34

General Philip H. Sheridan. Author’s collection.

Former Confederates in the Shenandoah loathed Sheridan not only for the destruction committed during the Burning but also for the time of year that he conducted his operation of desolation—autumn. With the devastation to fall harvests, it meant that the region’s inhabitants did not have an opportunity to replant and therefore confronted starvation during the winter of 1864–65.35 John O. Casler, a Shenandoah Valley resident who served in the Thirty-third Virginia Infantry, concluded after the war that it was the timing of Sheridan’s operations that brought such terrific economic devastation to the region and thus cultivated such great animosity toward Sheridan. “Poverty stared the citizens in the face, as this was in the fall season of the year, and too late to raise any provisions. Their horses and cattle were all gone, their farm implements burnt and no prospects of producing anything the next year,” Casler noted.36 Henry Kyd Douglas, who served with both “Stonewall” Jackson and Jubal Early in the Shenandoah Valley, recalled that it would be very difficult to forgive Sheridan and his army for the devastation. “I try to restrain my bitterness at the recollection of the dreadful scenes I witnessed…I saw mothers and maidens tearing their hair and shrieking to Heaven in their fright and despair and little children, voiceless and tearless in their pitiable terror,” Douglas wrote after the conflict. “It is an insult to civilization and to God to pretend that the Laws of War justify such warfare.”37

Even individuals who did not live in the Shenandoah Valley held Sheridan singularly culpable for the hardships endured by the valley’s inhabitants...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Introduction

- 1: “Reconcile…to the Conqueror”

- 2: “Sons of a Common Country”

- 3: “There Was Not So Much Treading on Eggs”

- 4: “Reconciliation…A Common Interest”

- 5: “Keeping the Appomattox Contract”

- Epilogue: “Hope for the Future”

- Appendix A

- Appendix B

- Notes

- Bibliography

- About the Author