![]()

Chapter One

The Darwins

Family, Friends, Religious Views

The coat . . . will never warm my body so much as your dear affection has warmed my heart, my good dear children. Your affectionate Father, Charles Darwin.

Emma knew her man well, and still loved him deeply. Charles returned her love in equal measure without truly understanding her after so many years.

They lingered at their favorite overlook above Lake Ullswater, quietly drinking in the view, alone in thought yet fully together in that moment. Their daughter Henrietta stood a few yards behind her parents, side-by-side with her husband Richard Litchfield—“the Litches” as her lovably irreverent Uncle Erasmus called them. Silently watching her parents, she was caught in a tangle of memories and thoughts.

The happy weeks of June 1881 in the Lake District would be Emma’s remembered treasure. Not as happy as their first visit two years earlier, when Charles could still scramble up outcropping rocks to get better views. His love of the scenery had revived his enthusiasm for life, and Emma loved to see it—the child-like openness of mind and heart that led her to love the young adult Charles just returned from his world-circling voyage on HMS Beagle. This time they knew the time remaining was short as they walked along the lakeshore. Charles was failing and would be gone before the next summer.

Emma felt his depression in the idle aftermath of his all-consuming book projects and ingenious experiments with pigeons, orchids, carnivorous plants, climbing plants, and earthworms. Charles felt spent after he finally put to bed his last book. He couldn’t conceive starting a new multi-year scientific project at his age, but it broke his heart to admit it. Collecting relevant facts, sorting them, comparing them, asking why this not that, speculating, theorizing, imagining all counterarguments, refuting, more collecting, writing, editing, more writing, persuading, promoting, adjusting, persisting, he had become “a kind of machine for grinding general laws out of large collections of facts,” as he put it. Scientific work had become his joy, his drug, his tonic, his obsession, his self-torture. His health predictably suffered from the intense anxiety of the mental work.

Eventually Emma learned the temporary cure—to whisk him away, with the family and household staff—away from the comforting but demanding routine of Down House to long seaside holidays, often against his will. Charles enjoyed these interludes, but too soon, separation from the drug of work would overtake Charles, and back to Down House they would go.

This time felt different.

Charles and Emma stood close together, as close as two people become after decades of truly successful marriage, watching rain clouds envelope the surrounding mountains and darken the lake to gun-metal gray. The penetrating breeze carried a mist of drizzle, chilling them, but not enough to drive them off their special promontory.

The Family

Charles was probably wearing the fur coat his grown children had given him the previous summer—it was a tearful surprise for an elder man sensitive to cold but disinclined to pay for luxury. Henrietta would have remembered her brother Frank arranging the fur coat as a surprise gift, in conspiracy with the butler Jackson and the other siblings. Frank’s letter to Henrietta described the caper and their father’s reaction:

Charles’s “delightful letter” ended with this:

Unlike most Victorian fathers, Charles was very close to his children and they to him. He played with them, listened to them, watched them with a scientific eye, worried for them, recruited them to assist in his experiments, conspired with them, cared for them. Still, he retained the formal manners of the well-bred gentleman, especially in writing. From the time his books brought fame and notoriety, he was always conscious that his letters might be studied long after he passed from the scene. He didn’t know that Frank would collect and edit two volumes of his letters for publication. Henrietta would do the same for their mother years later. They knew their parents well, but not as well while they still lived. In some respects, we cannot know our parents as well as their biographers would know them, but no one could ever know them as we do. Charles and Emma were so much a part of their children’s lives that all seven surviving children—William, George, Henrietta, Francis, Elizabeth, Leonard, and Horace, oldest to youngest—not only honored their parents but felt their love and loved them in return.

Arm in arm with Henrietta (“Etty” until the self-consciousness of young adulthood rendered the nickname undignified), Richard knew well enough to just stand with her in silent contemplation of the older couple and the magnificent view, allowing his wife to drift in thought.

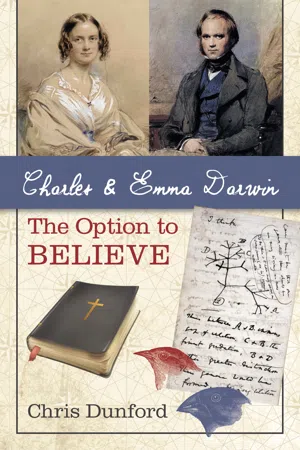

She could see her parents’ love for each other in their postures, at ease and close, quietly talking as they looked out on the lake. She imagined them as a young couple, recalling their 1840 portraits by Mr. Richmond, just a year after their wedding. Also the Wedgwood, Allen, and Darwin family reports that Charles had a rather ordinary face but pleasant to behold, especially when animated by his good manners and easy conversation. Emma was the youngest of Charles’s many Wedgwood first cousins (his mother Susannah [Sukey] was a Wedgwood), and Emma was reputed to be the prettiest, except perhaps the much older Charlotte. Emma was not considered a classical beauty, but her measured vivacity illumined face and figure to make them shine in speech, action, and interaction. Emma and Fanny, her sister just two years older, were known as “the Dovelies” for their lovely togetherness and were always welcome additions to family gatherings as well as parties in other country houses of Staffordshire and Shropshire.

Henrietta thought of the fun she and her siblings had at Down House. Not confined to “the nursery” or their own secluded space in the small mansion (an old parsonage, really), they had free run, even rearranging the furniture in the parlor for rough-and-ready games. She particularly remembered with a smile how they romped around that room while Emma, a superb pianist, hammered out her own “galloping tune” on the family’s grand piano.

Emma was never fastidious about keeping a tidy house (as a girl, she was known as “Little Miss Slip-Slop,” so unlike her very organized sister Fanny, “Miss Memorandum”). She let entropy have its way with the toys and clothes, until it became so topsy-turvy that she called in the housekeeper to clear it all up and restore order. Charles was by nature quite fastidious, so his tolerance was saintly—as long as the chaos did not invade his study. Even so, he did not overly mind the children bursting in to borrow scissors or other items deemed essential for their projects, as long as they respected his right to shush them out again and get the item back in good time.

Not that Down House was chaotic—quite the opposite. Emma oversaw with care and efficiency a household staff worthy of a country gentleman of property, led by their loyal and loving butler, Joseph Parslow (Jackson was a late-comer after Parslow’s retirement). Mrs. Evans was their cook for more than forty years. Their footmen, maids, and gardeners also stayed longer than usual because they enjoyed life and work at Down House. Emma organized household life around Charles’s needs, which included a daily regimen of meals, work in his study and in the garden or greenhouse, walks round the Sandwalk, reading newspapers or novels or listening to Emma read them aloud, listening to Emma playing the piano, playing with the children, attending to household and village business, and napping. Emma made it possible for Charles to be a “gentleman” meeting his responsibilities to family, household, and village and at the same time a remarkably productive “natural philosopher” (as scientists were called before mid-century), doing very original research and maintaining a massive correspondence with fellow scientists and other suppliers of information and specimens from all over the world. During some periods of months or years, the children and household staff could know the exact time of day by Charles’s methodical transitions from one activity to the next.

There were, however, other periods dominated by illness, most often Charles’s chronic and severe bouts of intestinal upset or headaches or dizziness or skin outbreaks, sometimes all at once, and even hysterical weeping (mostly at night). Though she struggled with her own health through ten pregnancies, Emma was Charles’s ever-patient and loving nurse, backstopped by Parslow. Whole weeks or months, even years, were lost to these symptoms—symptoms of self-imposed psychological stress, Emma suspected, but Charles persisted in believing their cause purely organic and probably heritable, stressing him even more with guilt when his children were mysteriously ill. So prevalent was childhood illness, and so often fatal, that Victor...