![]()

1 Pop Kills Poetry?

Interior. Night. The handheld, documentary-style camera moves unsteadily out from a dark corner to reveal the cluttered, poorly lit bedroom where Diego Luna’s teenage Tenoch is having sex, missionary-style, with his equally young girlfriend Ana (Ana López Mercado). His pale body and, most especially, his naked buttocks are centre frame through most of an unbroken sequence shot that lasts for a full two minutes. As there is no music, diegetic or otherwise, we can hear clearly the young couple’s orgasmic moans, followed by their graphic dialogue in which the verb ‘fuck’ (Mexican coger) is repeated over and over again. As the couple will be temporarily parted, each is promising the other not to succumb to the charms of foreign partners. With the lovers still in the act, the many nationalities of these imaginary rivals are incongruously (humorously) declaimed in turn, starting with ‘French fags’ (putos). Halfway through the sequence the couple change place and the naked girl is on top (the camera is constantly reframing). Suddenly, the ambient sound goes down, the camera retreats once more from the bed, and we hear for the first time the affectless voiceover of Daniel Giménez Cacho. It is describing Ana’s divorced mother, a member of one of the many broken families in the film. Although the mise en scène is unexceptional (shelves stacked with anonymous books, the dull red patterned fabrics of curtains and bedstead), a large movie poster is prominent on the wall behind the couple. It is for the French release of Hal Ashby’s Harold and Maude (1971), a cult movie on the romance between a troubled young man and a free-spirited older woman.

In accounts of Y tu mamá también’s creation, Alfonso Cuarón (who takes multiple credits as director, writer, producer and editor) is keen to draw a line between his then recent work as a film-maker for hire in Hollywood and his return to his home country for this passion project. Cuarón had made his feature debut with sex comedy Sólo con tu pareja/Love in the Time of Hysteria (1991), in which a Mexican macho, played by Daniel Giménez Cacho (later to provide the voiceover for Y tu mamá también), is taught a cruel life lesson when one of his many mistreated girlfriends falsifies his HIV test. Decamping to the US, Cuarón made two literary adaptations: A Little Princess (1995) was a tasteful period piece; Great Expectations (1998) a somewhat more daring updating of a classic Dickens novel to contemporary New York. Both fitted well within US paradigms of production at the time.

The initial premise of Y tu mamá también, we are told, was more simple, less calculated. In El Universal’s account, repeated elsewhere, it was cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki ‘El Chivo’ who had suggested as early as 1988: ‘What if we make a film about two weyes [dudes] who go to the beach?’ To this the brothers Cuarón responded with a single word: ¡Chido! (Cool!). The unapologetically Mexican Spanish, exotic to global speakers of the language, would prove to be essential to the distinctive dialogue of the film and to the international success of the final feature. This linguistic dimension was thus prominent even at the project’s birth.

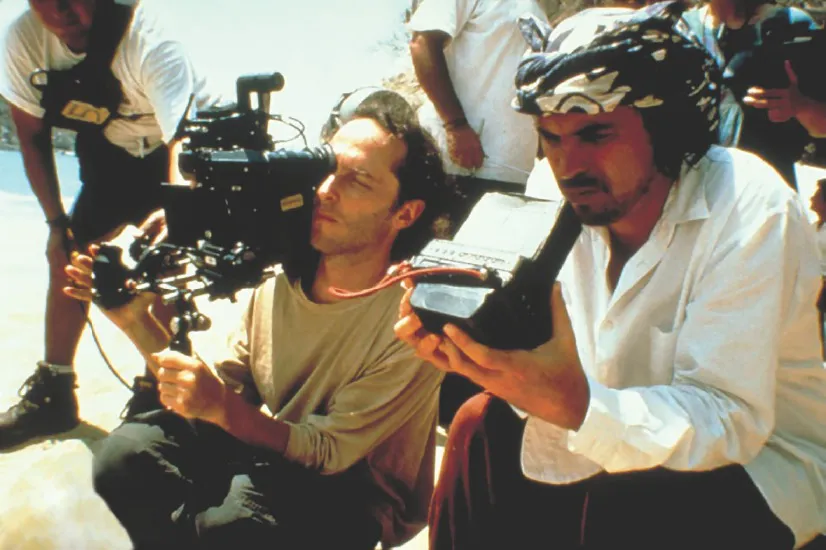

Lubezki (left) and Cuarón on the shoot

The millennium was not exactly a propitious time to make movies in Mexico. In a nation with a population of just over 100 million, only seven features would be produced with public support and fourteen with private funding in 2001, the year of Y tu mamá también’s release (by 2019, with Cuarón’s Roma still streaming on Netflix, the figures had swelled to a pre-pandemic peak of 105 and 111).3 One harbinger of renewal had been Alejandro González Iñárritu’s Amores perros the year before. Not only was this a critical and popular success that made the charismatic Gael García Bernal a star; it was also a production made without a peso from state sources. Its director and producers were proud of their independence from a cinema establishment that they identified with Mexico’s ancien régime, the PRI (Partido Revolucionario Institucional), which had ruled for over seventy years.

Following Iñárritu’s lead, Cuarón turned for support to businessman Jorge Vergara, CEO of Omnilife, a controversial nutritional supplement company, and owner of Chivas, Guadalajara’s famed football club. Non-actor Vergara (who is granted the only above-the-title credit in the film) was rewarded with the role of President of the Republic in the key scene where Julio and Tenoch meet the Spanish Luisa at a lavish wedding, although he is seen only from behind. Y tu mamá también would be the first feature made by Vergara’s shingle (later it would reunite García Bernal and Luna as footballer siblings in Carlos Cuarón’s comedy Rudo y Cursi [2008] in association with Canana, the production company set up by the actors themselves in 2005). The apt name of Vergara’s enterprise was Anhelo (‘longing’). It suggests the urgent desires of both Y tu mamá también’s characters and its creators, eager to set off on a cinematic journey together.

From left: Verdú, García Bernal, Luna and Cuarón on the shoot

Criterion’s release of the film offers in its extras no fewer than three distinct accounts of the making of Y tu mamá también, whose shoot began on 21 February 2001. They offer valuable versions of public self-fashioning by the film’s participants that contrast with the more objective press coverage that I treat later in this book, especially with regard to the media profiles of its cinematographer and cast. The unusual ‘making of’, described as an ‘on-set documentary’, offers a sarcastic introduction to the main participants in the production, voiced once more by a laconic Daniel Giménez Cacho. This playful early video insults all those who were involved in a production that was shot, wholly and by all accounts uncomfortably, in authentic locations. A Steadicam operator was hired but then never used, as El Chivo opted for a handheld shooting style. Cuarón himself is famous on the shoot for three exasperated lines: ‘Who’s not ready?’; ‘Have another beer, I’ll stress out for you’; and ‘Who’s the guilty party? I want names.’

Of the actors, Gael is just a ‘frustrated footballer’ (we see him contentedly kicking a ball about), while Diego, a telenovela star, is flattered when extras ask him for a signature (he doesn’t know the producers have paid them to do so). Meanwhile, Maribel Verdú, whose character is named after conquistador Cortés, has come to ‘conquer Mexico’ but, like her illustrious predecessor, suffers a disaster (a new ‘Noche Triste’, the ‘Sad Night’ of Cortés’s temporary defeat). In a carefully prepared but cruel prank, one of the hazing rituals traditionally inflicted on novices on Mexican shoots, Cuarón pretends that the boat in which she is sailing has run out of fuel and has the non-swimming actor fear for her life. Giménez Cacho announces, still deadpan, over a final snapshot of the crew taken at the end of their forced coexistence: ‘They’ll always be together. At least in the photo.’

The frat boy humour exhibited by the commentary is belied by visual evidence of the cast and crew’s meticulous care and craft which offers valuable documentation of the shoot. El Chivo struggles with the underwater camera in one of several tricky swimming pool sequences; the resentful crew is banned from the shoot during one of many nude scenes, where, in spite of the film’s free and easy depiction of sex, the actors’ intimacy on set is zealously protected; and Cuarón himself minutely directs even the extras: the bodyguards at the wedding graced by the president are instructed exactly how to stand as they eat their tacos and precisely which football match they are pretending to watch on their portable TV.

Unsurprisingly perhaps, two sets of interviews (from 2001 and 2014) offer a more nuanced approach in which the participants present themselves in markedly different ways to the film’s prospective audience. In the first a startingly young Cuarón confirms that the idea for the film came from before he made first feature, Sólo con tu pareja. Cuarón lends Y tu mamá también a very personal origin story. His son (future film-maker Jonas) had just turned 17; and, sick of the banal romantic teen movies of the time, Cuarón senior wanted to make a more realistic contribution to the genre. This new project would be based on a double journey: the conventional odyssey from innocence to experience of the two Mexican youngsters, Julio and Tenoch; and the less expected arc of the older married Spaniard, Luisa, who abandons her erring husband to travel with the boys but keeps secret from them (and us) her diagnosis of terminal cancer.

Also in Criterion’s video extra, Verdú herself confesses that she found the script ‘terrifying’, ‘tough’ and ‘disturbing’. García Bernal and Luna stress rather their long-time friendship before the shoot in spite of their equally durable rivalry for roles (there are just ‘three or four boys’ in Mexico who go up for everything). Cinematographer Lubezki invokes friendly familiarity also, naming Cuarón ‘his director’ and faithfully following him on a return trip to Mexico from his own successful career abroad. The pair agree that, paradoxically, Y tu mamá también’s approach to telling the story on film, ‘radically different’ from the earlier American features, was both less complex and more difficult than their previous projects. Lubezki aimed for the tricky sweet spot of a naturalism that would not be misrecognised as documentary. For Cuarón the new film was both harder than his Hollywood films, because of its smaller budget and crew, and simpler because of that same crew’s commitment and energy.

Thirteen years later the team reflects on the shoot of a now classic film with the luxury of hindsight. Cuarón, feted for his prize-winning English-language features Children of Men (2006) and Gravity (2013), calls Y tu mamá también his first ‘conscious film’ after having been ‘lost’ in the Hollywood system. Carlos Cuarón, his co-screenwriter, says that although he loved the American comedy of Lubitsch and Blake Edwards, his references here were to the French nouvelle vague (the narration was cribbed from Godard). Making rare metaphysical claims for the film, not offered to the press at the time of his film’s release, Alfonso says that its moral is that ‘everything is transient’; and openly claiming it as a national narrative, he calls it an allegory of ‘Mexico on the brink of transformation’ at the end of the PRI regime.

The central characters’ full names now seem not quite so parodic, encompassing as they do the history of Mexico. As mentioned earlier (and as critics have also noted), ‘Luisa Cortés’ is named after the conquistador. ‘Tenoch Iturbide’ combines two leaders, the perhaps mythical Mexica (Aztec) warrior who founded the settlement (Tenochtitlan) that would become Mexico City and an ill-fated emperor in the aftermath of independence from Spain. ‘Julio Zapata’ is named after Mexico’s most celebrated and virile revolutionary, an ironic baptism for a scrawny teenager. Cuarón admits to employing the changing power balances between this central trio of actors to feed the dynamic of their characters. An established star in Spain with over fifty credits in film and television, Verdú at first intimidated her less experienced Mexican co-stars. But, like her character, she soon found herself alone, a stranger in a strange land. She even required an eight-page glossary to decode her co-stars impenetrable chilango (Mexico City) slang. As shooting progressed Verdú, like her character Luisa, regained her composure, claiming that when they filmed their first sex scene (the movie was shot, unusually, in sequence) Diego Luna was ‘shyer’ than she was on set.

When Cuarón talks in the 2014 interviews of ‘conflicts’, it is not always clear if he means between the actors or their characters. Both boys describe Cuarón as a ‘bully’ and a ‘nightmare’, recalling ‘physical fights’ with him. Yet despite the apparently casual shooting style, there was, we are told, no improvisation on the set, as every detail was worked out in advance. When Verdú told the director that she had channelled authentic emotion in one of the touching scenes in which she was required to weep, Cuarón told her coldly to ‘feel it less’. What the director calls ‘moments of truthfulness’, in which the camera seems simply to ‘witness’ the action, are thus the result of a controlled and conscious technique by all concerned (we shall see that Verdú is keen to confirm this point in interviews with the Mexican press). It is telling that, unlike in his Hollywood films, Cuarón chose here to avoid subjective (point-of-view) shots. Aiming for objectivity, he situated the characters firmly in their settings with the use of wide angles that made them ‘surrender to their environment’. And if one striking scene is shot on the fly amidst a real-life student demonstration in the capital, scouting for the main locations of the action in Mexico City and the southern states of Puebla and Oaxaca took several laborious months.

Likewise, the film’s final fluid threesome between Tenoch, Julio and Luisa was,...