![]()

Select Battles & Campaigns

Lexington and Concord, Battles of (Boston Campaign)

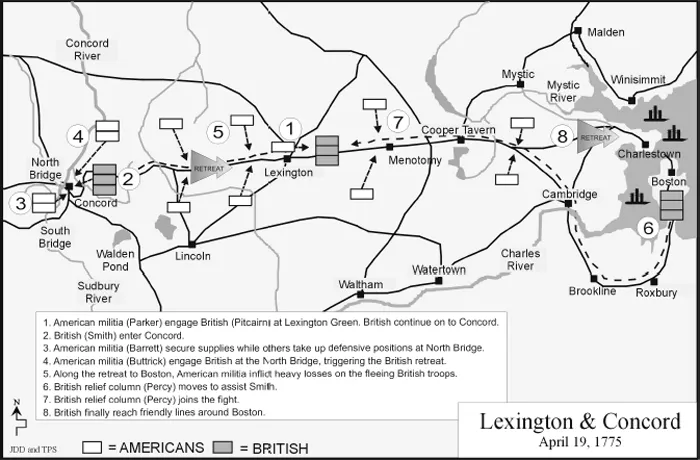

Date: April 19, 1775

Region: Northern Colonies, Massachusetts

Commanders: British: Lieutenant Colonel Frances Smith, Major John Pitcairn, Major (Lord) Hugh Percy; American: Captain John Parker (Lexington), Colonel James Barrett (Concord and along British retreat to Charlestown-Boston)

Time of Day / Length of Action: Early morning (Lexington and Concord), morning and afternoon (retreat to Boston)

Weather Conditions: Unremarkable, clear and pleasant

Opposing Forces: British: 700-man force of infantry, grenadiers, Royal marines with cavalry escort (reinforced with 1,000 soldiers and two cannons during retreat phase); American: 70 at Lexington; 200 at Concord, with more along British retreat to Charlestown (loosely organized local militia units).

British Perspective: By the spring of 1775, the American colonies were on the verge of revolt. Nowhere was this radical energy more fervent than in Boston and the surrounding countryside, where British troops eyed the locals with justifiable suspicion. In the port of Boston, British authorities focused closely on the export businesses as local merchants sought ways around the numerous tariffs imposed by the Crown. Smuggling was rampant. New Englanders avoided high taxes by trading illegally with the Dutch and French. Violent protests in the streets of Boston reached a new phase on March 5, 1770, when British troops fired into a mob killing five protestors. Anti-British sentiment escalated over the next few years.

In May of 1774, Lt. Gen. Thomas Gage, the commander-in-chief of the British Army in America, returned to the colonies after a leave in England and assumed command as the military Royal Governor of Massachusetts. Rebellion loomed as the Crown implemented additional retaliatory measures for what it deemed rebellious acts against the King’s authority.

The colonials established a Massachusetts Provincial Congress in May 1774, which met illegally in Concord. Its leadership included John Hancock and Samuel Adams. In February of 1775, Parliament declared the colony of Massachusetts to be in open rebellion and authorized British troops to kill violent rebels. General Gage was ordered to quell the rebellious behavior. He was instructed to arrest the membership of the Massachusetts Provincial Congress, but decided instead to seize arms and munitions stored at Concord. During the early hours of April 19, he dispatched troops under Lt. Colonel Frances Smith and Maj. James Pitcairn to seize these munitions.

American Perspective: Burdensome taxes imposed by the Crown were enacted to recoup expenditures of the French and Indian War, but the American colonists despised the British authorities for their heavy-handed tactics. Between 1763 and 1765, the Americans were hit with the Sugar Act, Currency Act, and Quartering Acts. In 1767, the Massachusetts House of Representatives officially denounced a new tax known as the Townshend Act. Hailing these acts passed in England as “taxation without representation,” disgruntled colonials subject to the Crown expressed their displeasure loudly and frequently. Royal Governor Sir Francis Bernard sought assistance from British authorities and on October 1, 1768, Boston was occupied by British soldiers. Parliament eventually repealed the Townshend Act, but its tax remained on imported tea. In 1773, the East India Trading Company enjoyed British favor as the primary importer of colonial tea, and an official decree known as the Tea Act was established to enforce it as policy. The colonists consumed tea with a passion, and the increased prices served only to further anger them.

On December 16, 1773, colonists covertly boarded an East Indian merchant ship laden with tea and poured it into the harbor. The consequence of what came to be known as “The Boston Tea Party” was the passage of a new imposition known as the Intolerable Acts, which included the closure of the port of Boston until restitution for the lost tea was made to the Crown. Previously elected officials were replaced with appointed British authorities, and private homes were seized to quarter British troops.

The establishment of the Massachusetts Provincial Congress in May 1774, coupled with the increased rhetoric against the Crown’s authority, left the region a dry tinderbox awaiting a spark that arrived in the form of British troops marching from Boston to Concord.

Despite British efforts to march in secret to Concord, a network of local spies sounded the alarm. Two Bostonians, Paul Revere and William Dawes, avoided capture and slipped out of the city into the countryside. Before his departure Revere placed lanterns in the Old North Church to signal movement details of his enemy (which resulted in the well-known mantra “One if by land or two if by sea”). Dawes and Revere traversed different routes to warn colonials in Lexington that the British were on the march toward Concord. In Lexington, which lay on the road to Concord, another colonist named Samuel Prescott joined the “midnight riders” in order to spread the word to the rebels. British cavalry patrols captured Revere and forced Dawes away from the area, but Prescott reached Concord.

Shortly after Revere was captured the rebels assembled on Lexington Green. Led by their militia commander Capt. John Parker, the “Minutemen” waited for the main body of British troops marching rapidly toward Concord. The British would have to march through Lexington to reach their destination. The first clash of what would be a long hard war awaited them there. As the British approached the rebel position and the sunlight rose in the eastern sky, a scout returned with word the enemy had arrived.

Terrain: Gently rolling fertile farm region. Lexington and Concord are both small New England towns. In Lexington, the brief fight occurred on the town green. The Concord action began at the Concord North Bridge and continued along the retreat route to Charlestown, a dirt road lined with alternating forests and fields that provided the colonial militia with advantageous areas for picking off the retreating British soldiers.

The Fighting: (Battle of Lexington): Captain Parker organized his men on the town green to interrupt the march of the approaching British. The sun was just rising. The handful of rebels quickly realized they were heavily outnumbered and that defeat was inevitable. Captain Parker ordered his men to disperse. Exactly what took place next is not clear. As the British soldiers reached the green, someone may have fired into the British forces from behind a stone wall. Other shots rang out. Under Major Pitcairn’s direction, the British returned fire and assaulted the colonials. The skirmish ended quickly with the blood of eighteen rebels spilled onto Lexington Green (eight killed, ten wounded).

Battle of Concord: The British resumed their march to Concord, six miles distant. News the British were coming had reached Concord about 2:00 a.m., and several companies of minutemen turned out. Local militia leader Col. James Barrett led a contingent of men to remove munitions and military stores from his property and conceal them elsewhere. Others watched for the enemy from a ridge lining the road leading to town. They fell back when the Redcoats approached Concord between 7:00 and 8:00 a.m. Captain Lawrence Parsons led three companies to search homes and farms to uncover the hidden weapons and powder while three other companies under Capt. Walter Laurie secured the North Bridge. The British set fire to several cannon mounts in the courthouse. The colonials watched in horror, certain the enemy was torching the town.

![]()

![]()

By this time (perhaps 9:30 a.m.), 300 to 400 militia had gathered on the high ground above the North Bridge. With fife and drum Maj. John Buttrick led his motley group of farmers and merchants toward Laurie’s companies defending the span. Laurie ordered his men to fall back to the opposite side of the bridge, where they deployed in a tight in-depth defensive formation that allowed only one of the three companies to fire on the approaching rebels, who continued advancing unaware of the brief fight at Lexington. When the British opened fire the rebels confidently returned it. The exchange lasted for several minutes and eventually drove the Crown’s professional soldiers back in some disorder into Concord. They left three killed and eight wounded on the field. The Americans, who suffered two killed and three wounded, made no real attempt to pursue Laurie or cut off the column of British out searching Barrett’s farm. A chagrined Lieutenant Colonel Smith led his men out of Concord about noon, cognizant that the force of Massachusetts militiamen was growing.

Retreat to Charlestown: The British passed through a hail of enemy lead as they withdrew from Concord to Lexington. Just outside Lexington, Captain Parker, who had earlier led the militia on Lexington Green, organized an ambush known today as “Parker’s Revenge.” Parker’s surprise attack inflicted many casualties and wounded key British leaders, including Lt. Col. Francis Smith. A British relief force led by Maj. (Lord) Percy joined Smith’s column at Lexington. Without Percy’s men, artillery, and leadership, the colonials may have overwhelmed and destroyed Smith’s expeditionary force. Using his cannon to disperse the advancing rebels, Percy regained some control of a difficult withdrawal. Although Percy managed to lead the British column back to the safety of Charlestown, the rebels fired on it from the woods throughout much of the march, inflicting several hundred casualties. By the time the march ended, some 6,000 colonial militiamen had assembled on the outskirts of Boston.

Casualties: British: 73 killed, 174 wounded, and 26 missing; American: 49 killed, 41 wounded, and five missing (most losses on both sides incurred during the running battle to Charlestown).

Outcome / Impact: The Battles of Lexington and Concord (“The Shot Heard Round The World”) initiated armed hostilities between the British and American forces. The bloodshed was exactly what many in the colonies were hoping for to raise popular support for an armed revolution. The colonial fighting style was unconventional and disorganized, but the asymmetric form of warfare had a tremendous impact upon the morale of the British soldiers, who suffered nearly 20 percent casualties. The seemingly invincible British army suddenly found itself in a war fighting an enemy who used tactics as foreign to them as the soil upon which they were fighting. Colonial Gen. William Heath organized the thousands of militiamen milling about outside Boston and established a quasi “siege” around Gage’s shocked British command. The war was now on in earnest.

Today: The Minute Man National Historical Park in Concord interprets and preserves these opening battles of the war through exhibits and living history programs.

Further Reading: Tourtellot, Arthur Bernon, Lexington and Concord: The Beginning of the War of the American Revolution (Norton, 2000); Forthingham, Richard, History of the Siege of Boston and the Battles of Lexington, Concord, and Bunker Hill; Also, An Account of the Bunker Hill Monument with Illustrative Documents (Scholars, 2005); Hibbert, Christopher, Redcoats and Rebels: The American Revolution Through British Eyes (Norton, 2000).

Fort Ticonderoga, Battle of (Canadian Campaign)

Date: May 10, 1775

Region: Northern Colonies, New York

Commanders: British: Captain De La Place; American: Colonel Ethan Allen and Captain Benedict Arnold

Time of Day / Length of Action: Dawn

Weather Conditions: Unremarkable, spring morning

Opposing Forces: British: 85; American: 100 Vermont militiamen

British Perspective: Hostilities in Massachusetts were far removed from the stone ramparts of Fort Ticonderoga. Although the revolution had been underway for several weeks, most of the British outposts and garrisons in North America, including Ticonderoga, remained undermanned and isolated. As with any frontier outpost, the drudgery of daily routine and isolation dulled the senses and lulled inhabitants into a false sense of security. Fort Ticonderoga was built by the French in 1755. By 1775 the post was armed with 79 pieces of heavy artillery, but had a garrison of only 85 soldiers. British authorities, however, believed it was adequately defended. There was no indication local citizens were preparing for an assault on the fort or that any hostile force was approaching.

American Perspective: Following the Battles of Lexington and Concord, the Second Continental Congress called up a national standing army, naming George Washington as its commander. Washington opened a quasi-siege against the British in Boston, Massachusetts. He and his officers realized from the outset they were short on nearly everything an army required, especially artillery and ammunition. The British outpost at Fort Ticonderoga 200 miles to the north had both guns and powder in substantial quantities. If the fort could be taken, its resources and strategic location would meet other needs as well. Colonel Ethan Allen organized a 100-man force of Vermont militiamen (known as the Green Mountain Boys) to conduct the difficult mission. Joined by Connecticut militia leader Captain Benedict Arnold, the Patriot force launched its effort to capture the British fort.

Terrain: Located in Essex County, New York, 95 miles north of Albany, Ticonderoga derived its name from the Indian word Cheonderoga, or “Place between two waters.” Fort Ticonderoga was strategically located on dominating high ground surrounding the area between Lake Champlain and Lake George in the Hudson River Valley.

The Fighting: Before dawn on May 10, the Green Mountain Boys stealthily crossed Lake Champlain from Vermont into New York. The Vermonters crept undetected up to the fort’s stone walls. To their surprise, the raiders discovered an unmanned and unlocked entrance, through which they quietly entered the bastion. As they hoped, except for a single guard the garrison was sound asleep. A brief fight broke out during which the lone British guard and a Vermonter were wounded. The Americans moved quickly to the commander’s quarters, where Captain De La Place awoke slowly to the realization that his fortress had been captured by the enemy. When Colonel Allen demanded his surrender, the sleepy De La Place, who was still in his ...