![]()

1

From Nikolsburg to Ems

The completeness of the Prussian success in 1866, and the speed with which it had been achieved, took all Europe by surprise. The brilliance of the victory brought Helmuth von Moltke in an instant out of the shadows to become the best known soldier in Europe. His own comments after the ending of the campaign were expressed in measured terms. He wrote to his cousin Edward Ballhorn on August 8 that ‘even if I do not rate my share in the matter so highly as you do out of goodwill towards me, I have at least the comfortable consciousness of having done my duty. The grace of God was clearly with us, and we can all wish ourselves joy of the consequences, for indeed it was a matter of life and death.’ He was not unmindful, however, of the extent of the achievement; ‘a campaign so swiftly ended is unheard of; after exactly five weeks we are back in Berlin.’1 He felt, though, profound distaste for the ‘fulsome praise’ which he received, which he said upset him for the whole day. As he saw it, he and his comrades had merely done their duty, and he reflected on the ‘indiscriminate censure’ and ‘senseless blame’ that would have been his lot if, like Benedek, he had returned home in defeat. For his luckless adversary he felt the deepest compassion. ‘A vanquished commander! Oh! If outsiders could form but a faint conception of what that means! The Austrian headquarters on the night of Königgrätz – I cannot bear to think of it. A General, too, so deserving, so brave, and so cautious.’2

The international political consequences of the Prussian victory were of course profound. The expectation, or at least the hope, felt by many in the French government at the outset of the war that it would in some way lead to some useful benefits for France meant that Napoleon's acquiescence in Bismarck's terms for ending the war left a very bad taste in their mouths. There immediately began a struggle to develop a policy that would lead to France after all getting something out of the situation. Drouyn de L'Huys in particular clung to the belief that, in exchange for neutrality, France would be able to present a bill to Prussia in the form of a request for territorial compensations and get a favourable response. It was, after all, what Bismarck had at times led Napoleon to expect. But by the time the details of the invoice were finally settled, the terms of peace were ready for signature at Nikolsburg, and Bismarck had no difficulty in brushing aside Benedetti, the French Ambassador, when he sought to raise the subject of payment.

The feeling, as Thiers put it, that ‘it is France that is beaten at Sadowa,’ was a powerful one. The events of July 3 cast a long shadow, and thereafter defined the fundamental relationship between France and Germany. Emile Ollivier, who was to become French Premier in 1870, was in no doubt as to its significance, both for the government he led and for his nation.

The first cause of the War of 1870 is to be found in the year 1866. It was in that year, to be marked forever with black, it was in that year of blindness when one error was redeemed only by a more grievous error, and when the infirmities of the government were made mortal by the bitterness of the opposition; it was in that accursed year that was born the supreme peril of France and of the Empire.3

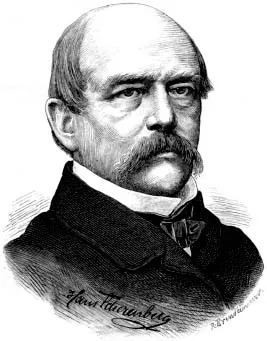

Bismarck (Pflugk-Harttung)

In the first shock of the news from Northern Bohemia there had been sharply divided views in Paris about the feasibility of armed action.

The higher levels of the French Army expected intervention as a matter of course and were innocent of any abnormal anxiety on the subject… Canrobert, Valazé, Chasseloup-Lambert, Bourbaki, and Vimercati all awaited or actively promoted military steps. The prevailing mood in the upper echelons of the army appears to have been one of readiness and even eagerness.’4

Napoleon himself, however, remained firmly of the view that France was not ready to risk war. He told Cowley, the British Ambassador, that the stationing of an army of observation on the frontier, as had been urged by the Austrian Ambassador Richard Metternich, ‘in the present excited state of Germany… would have no effect. On the contrary, insolent questions as to his intentions would be put to him, and war would be the consequence. But he was not prepared for war, nor could he be under two months.’5 This was also the view of foreign observers; the astute Colonel von Löe, the Prussian Military Attaché in Paris, had been saying much the same thing before the outbreak of war, and views of this kind, strongly supported by Moltke, sustained Bismarck when he called Napoleon's bluff over the Nikolsburg terms.

Napoleon's demand for compensations, as a modern historian has pointed out, originated rather as a ministerial policy than as a popular demand. For this reason it had been pursued during the Nikolsburg negotiations too late to achieve anything; and perhaps it was always half hearted because the policy was seen as likely in any case to prove ineffective. Since it was devised as a means of removing what was supposed to be popular dissatisfaction with the whole of French policy during the recent German crisis, it is certainly true that ‘French opinion as a whole was only indirectly responsible for the policy.’6 Goltz, however, the Prussian Ambassador, held firmly to the view that the demands for compensation were indeed ‘brought about by the state of public opinion in France.’ He told Cowley that Eugénie had said to him ‘that she looked upon the present state of things as “le commencement de la fin de la dynastie”.’7 At all events, Napoleon had to content himself with the publication in September of a diplomatic circular in which he represented the events of the last three months as a triumph of French policy, and in which he sanctimoniously disavowed any self interest in the territorial aggrandisement of France.

But the shock to the French system caused by the stunning Prussian victories was not just a matter of injured pride, although in terms of the Bonapartist dynasty it was always a matter of what was apparent rather than what was real. So profound was the feeling of dismay that gripped many that moved in court circles in France that it fuelled thereafter Napoleon's concern to achieve some success to offset the effect of the Prussian victory; as the years went by, his failure to do so created a vicious spiral which was to exercise a fatal influence on the decision making process in July 1870.

No war could ever be properly regarded as entirely inevitable, but the language of both contemporary observers and subsequent historians can make it seem so. When those whose responsibility it is to take decisions that may lead to war come to believe that sooner or later it is in any case inevitable, the most effective moral brake upon their progress down the slope is removed. It is at this stage that, necessarily, the influence of those who will have the conduct of the war itself, the military leaders, may become decisive. And if they can see that there exists the possibility that the military balance will at some time in the future begin to tip against them, that influence may be directed towards immediate action. The complexities of the mobilisation of an army in the second half of the nineteenth century exerted for this reason a strong thrust on the accelerator.

Certainly the language of those at the centre of events suggested that a Franco-Prussian conflict could not be avoided. In Paris, Colonel Claremont, the British military attaché, summed up the generally held view of most foreign observers of French military opinion when he wrote:

That the war against Prussia is certain at some future date does not seem to be doubted for a moment by any officer in the Army. Time may modify their views, but I never saw them so excited on any subject; the most sensible, the quietest, and most reasonable amongst them say openly that it is a question of existence for the Emperor, and that the aggrandisement of Prussia renders it imperative that they should again have the Rhine as their frontier line.8

It was a view which Cowley repeated to Lord Stanley, albeit with a different emphasis. Although, as he remarked, he was generally ‘mistrustful’ of his own judgement on internal matters, he wrote: ‘I hear on all sides that there is great dissatisfaction in the country, and particularly in the Army, not that people care one sixpence about an extension of the frontier, but that they cannot stomach the favour displayed by the Emperor towards Prussia. War is in general looked upon as inevitable.’9

Public opinion, at least as he perceived it, continued to weigh on Napoleon's mind as 1866 drew to a close. France, he told Cowley, was suffering under ‘une malaise et une mécontentment’ which, although not justified, he believed to be due ‘entirely to the position which Prussia had taken and which has aroused or rather revived, the ancient animosity of the French towards her.’ He went on to complain that intentions were attributed to him which ‘together with the insinuations of the German press that France would be obliged to restore Alsace and Lorraine to Germany, were doing incredible mischief.’10 Jingoistic press comment in these terms, on both sides of the border, kept the temperature high. In May 1868, for example, an anonymous pamphlet appeared in France publicly advocating a ‘sharp, short but decisive’ preventive war with the object of defeating Prussia before she reached a position of equal military strength.11

Almost certainly Napoleon privately recoiled from the horror and uncertainties of war with Prussia; but both he and Eugénie were prepared to stoke up the fires of French belligerence whenever they supposed it might help. During his abortive attempts to acquire Luxembourg in 1867, he told Goltz that if the Dutch King signed the proposed agreement and the Prussians refused to evacuate the Federal fortress that they still garrisoned there, he did not see how war could be avoided. A few days earlier, a more convincingly menacing tone was displayed by Eugénie, when according to Cowley she told Metternich that they ‘were very much annoyed with Prussia’, but that they were not grumbling, ‘for a great nation should not complain until she is ready to act….military preparations were proceeding on a grand scale and she hoped that everything would be ready by the end of the year.’ Metternich concluded that she felt ‘that war with Prussia is inevitable, sooner or later, and that both sides are playing for position.’12 The danger remained that utterances of this kind could be drawn from France's leaders whenever it was supposed that public opinion was or might become discontented with the regime; Napoleon was regularly speaking to Cowley of the state of opinion in France as being such that ‘matters could not remain for any length of time in their present uncertain state’.

And yet Napoleon was not lacking in sources of advice that were both cooler and better informed than those available to him in the hothouse atmosphere of Paris. Stoffel, his military attaché in Berlin, sent home a stream of thoughtful and analytical reports on the state of the Prussian army and, from time to time on the general situation. When expressly asked by Napoleon to report on the prospects of war, he set out his views on August 12 1869 in unambiguous terms:

1. War is inevitable, and at the mercy of an accident. 2. Prussia has no intention of attacking France; she does not seek war, and will do all she can to avoid it. 3. But Prussia is far sighted enough to see that the war she does not want will assuredly break out, and she is, therefore, doing all she can to avoid being surprised when the fatal accident occurs. 4. France, by her carelessness and levity, and above all by her ignorance of the state of affairs, has not the same foresight as Prussia.13

Stoffel's opinions were entirely consistent with those of Benedetti, the French Ambassador, who also emphasised repeatedly that France need have no fear of an unprovoked assault by Prussia. Bismarck's objective, he wrote on January 5 1868, was

not to attack us, as I have said, and as I repeat at the risk of assuming a grave responsibility, because this is my profound conviction; his end is to free the Main and to reunite South Germany to the North under the authority of the King of Prussia; and I would add that he proposes to achieve it, if necessary, by force of arms should France openly obstruct this.14

Although feelings on the other side of the Rhine were somewhat calmer than those in France, a sense that conflict must sooner or later arise was wide spread. Moltke was one of those who had always regarded war with France as inevitable. His own responsibility was, as he saw it, to be ready for it whenever it came. In May 1867, writing to his brother Adolf, it seemed to him unlikely to his regret that this would be in the immediate future, since

the Luxembourg question will hardly lead to war just at present. Louis Napoleon must be aware that he is not prepared for it; but he cannot say so to his vain Frenchmen; public opinion is much excited in Paris, fomented by party spirit, and an explosion is not impossible. Nothing could be better for us than that war, which is bound to come, should be declared at once, while Austria is, in all probability, engaged in the East.15

In the following year, musing on Napoleon's position, he wrote to Adolf: ‘I cannot believe that the domestic difficulties of France would ensure peace. On the other hand he will only play the “va banque” of war when he sees no other way of holding on. The better guarantee lies in the fact that France alone is too weak, and Austria not ready.’16

In Germany, as elsewhere in Europe, there was a generally held understanding that the most serious threat to the general peace was to be found in French territorial ambition. This belief, added to the traditional German fear and dislike of the French character, certainly confirmed Moltke in his view that war was bound to come. In 1860 in one of his earlier memoranda, he had noted that France ‘aims at the annexation of Belgium, the Rhenish provinces, and possibly Holland. Further she would have the certainty of such territorial gains in the event of the Prussian armies being held upon the Elbe or Oder.’17 The bruises inflicted by Königgrätz upon French national pride would certainly bring the risk of conflict closer still. In November 1866 Moltke found it necessary to strengthen the process of intelligence gathering in France, appointing the 33 year old Captain Alfred von Schlieffen to Löe's staff in Paris with the object of building up a reliable picture of French war planning.

The climate of opinion in Court circles reflected the general perception in Prussia of French attitudes. The Crown Prince, by no means a bellicose influence, observed in February 1867 to Bismarck that ‘there is no denying the fact that our policy is endangered by the malevolence and ambition of France. We must face the danger boldly, but it is too great for us to provoke; I am, however, greatly reassured by the decided manner in which you expressed the desire to me on January 31 to avoid a war with France.’18 Looking back, Bismarck himself felt that perhaps he had overrated the risk of war with France, which he never supposed he could avoid, but which he sought to delay as long as he could.

I did not doubt the Franco-German war must take place before the construction of a United Germany could be realised. I was at that time preoccupied with the idea of delaying the outbreak of this war until our fighting strength should be increased. I considered a war with France, having regard to the success of the French in the Crimean War and ...