- 168 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The Civil War historian and author of

A Season of Slaughter continues his engaging account of the Overland Campaign in this vivid chronicle.

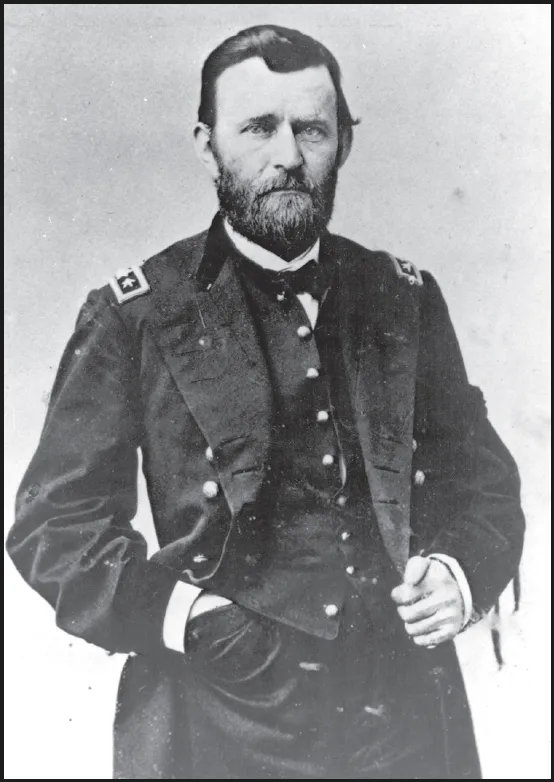

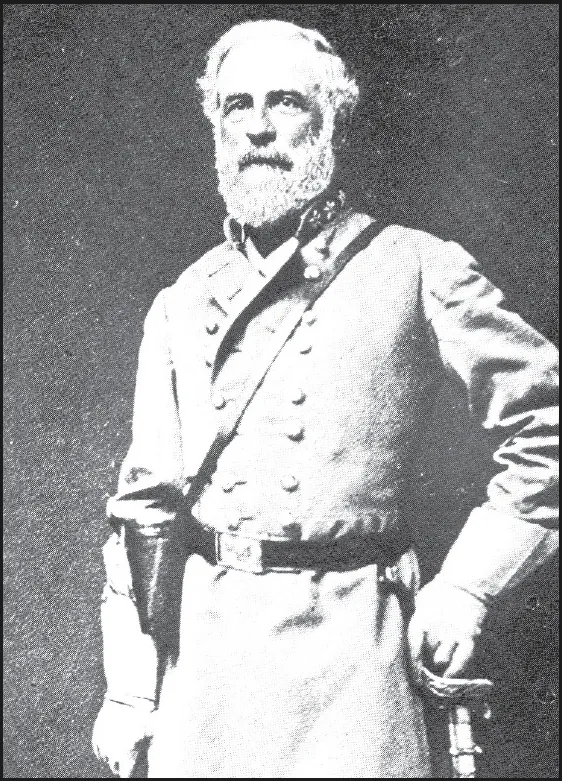

By May of 1864, Federal commander Ulysses S. Grant had resolved to destroy his Confederate adversaries through attrition if by no other means. Meanwhile, his Confederate counterpart, Robert E. Lee, looked for an opportunity to regain the offensive initiative. "We must strike them a blow," he told his lieutenants.

But Grant's war of attrition began to take its toll in a more insidious way. Both army commanders—exhausted and fighting off illness—began to feel the continuous, merciless grind of combat in very personal ways. Punch-drunk tired, they began to second-guess themselves, missing opportunities and making mistakes. As a result, along the banks of the North Anna River, commanders on both sides brought their armies to the brink of destruction without even knowing it.

By May of 1864, Federal commander Ulysses S. Grant had resolved to destroy his Confederate adversaries through attrition if by no other means. Meanwhile, his Confederate counterpart, Robert E. Lee, looked for an opportunity to regain the offensive initiative. "We must strike them a blow," he told his lieutenants.

But Grant's war of attrition began to take its toll in a more insidious way. Both army commanders—exhausted and fighting off illness—began to feel the continuous, merciless grind of combat in very personal ways. Punch-drunk tired, they began to second-guess themselves, missing opportunities and making mistakes. As a result, along the banks of the North Anna River, commanders on both sides brought their armies to the brink of destruction without even knowing it.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Strike Them a Blow by Chris Mackowski in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & American Civil War History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

The Campaign

CHAPTER ONE

MAY 1864

“The sun went down red,” noted Surgeon William Morton as he surveyed the blighted landscape around Spotsylvania Court House. “The smoke of the battle of more than two hundred thousand men destroying each other with villainous saltpeter through all the long hours of a long day, filled the valleys, and rested on the hills of all this wilderness, hung in lurid haze all around the horizon, and built a dense canopy overhead, beneath which this grand army of freedom was preparing to rest against the morrow.”

It was May 18, 1864. That morning, Federal commander Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant had ordered another massive assault against Confederate fortifications. Unbeknownst to him, though, they were the strongest field fortifications yet seen in the eastern theater. His attack ended in disaster.

“Our lines advanced splendidly to within three hundred yards of their works when they opened their Artillery and mowed the men down in rows,” said Rhode Islander Elisha Hunt Rhodes. “We stood it for two hours and then fell back to our own works where we have fortified. Our loss is fearful.”

When the smoke of battle cleared away, it “disclosed the ground for long distances thickly strewn with our dead and dying men,” said engineer Wesley Brainerd. “It was an awfully grand spectacle, one often repeated around that ground which has been justly styled ‘Bloody Spotsylvania.’”

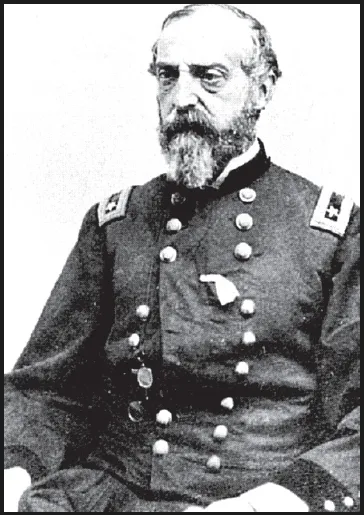

Such scenes had revealed themselves all too frequently since the start of the spring campaign. Major General George Gordon Meade, commander of the army of the Potomac, had marched south across the Rapidan River on May 4 to confront his Confederate counterparts for another season of battle. Traveling with him was Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, commander of all Union forces. “Lee’s army will be your objective,” he told Meade. “Wherever Lee goes, there you will go also.”

THE CAMPAIGN THROUGH MAY 20—Since the campaign opened in early May, the armies had been in constant contact, fighting in the Wilderness, skirmishing along the Brock Road, and fighting again around Spotsylvania Court House. Unable to score a decisive victory over Confederates after nearly three weeks, Federals looked to once more outflank them by moving east and south.

This represented a major strategic shift for the North, which had always sought to end the war by capturing the Confederate capital. “On to Richmond!” had always been the battle cry.

No more. Grant intended “to hammer continuously against the armed force of the enemy and his resources, until by mere attrition, if in no other way, there should be nothing left to him.”

Historically, this has always been interpreted as Grant’s war of attrition, but in fact, Grant didn’t have unlimited time to slowly wear away the Confederates. The presidential election in November imposed an unforgiving deadline. If Grant did not somehow come up with the big win that had thus far eluded the Federal army in the east, Lincoln’s prospects for reelection looked bleak. It was, therefore, a war of annihilation Grant intended to wage—one that would overwhelm the Confederates with superior might.

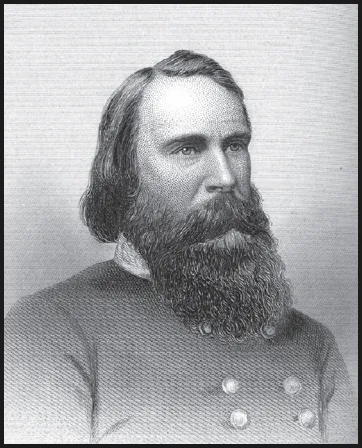

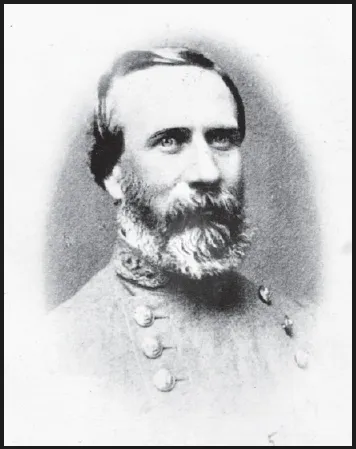

Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant (top) and Gen. Robert E. Lee (above) were both aggressive commanders. The spring campaign would finally pit them against each other. “There is no enthusiasm in the army for Gen. Grant,” said a colonel from Maine shortly after Grant assumed command of the Federal armies; “and, on the other hand, there is no prejudice against him. We are prepared to throw up our hats for him when he shows himself the great soldier here in Virginia against Lee and the best troops of the rebels.” (loc)(loc)

Regardless of the terminology, it represented grim arithmetic to be sure—but Grant proved to be the exact kind of mathematician President Lincoln had been looking for.

And exactly what the Confederates feared. Time was their greatest ally. They, not Grant, were waging the war of attrition, dragging out the bloodshed until Election Day, wearing down the Northern will to continue. “If we can break up the enemy’s arrangements early, and throw him back,” predicted Lt. Gen. James Longstreet, “he will not be able to recover his position nor his morale until the Presidential election is over, and we shall then have a new President to treat with.”

Longstreet, First Corps commander in the Army of Northern Virginia and the army’s second-in-command, knew what it meant to have Grant traveling with the Army of the Potomac. “That man,” he worried, “will fight us every day and every hour till the end of the war.”

* * *

Maj. Gen. George Gordon Meade, commander of the Army of the Potomac, found himself the odd man out as Grant took over more and more of the army’s operational control. (loc)

When the Army of the Potomac launched its spring offensive for 1864, it did so with the power of 123,000 soldiers. In comparison, the Confederates mustered some 66,000 men.

Confederate commander Gen. Robert E. Lee didn’t know the exact disparity, but the Federals had always outnumbered his army, and he expected this spring to be no different. To counterbalance that mismatch, he launched a sudden strike against the Federals on May 5 as they tried to move through the Wilderness, a 70-square-mile tangle of second-growth forest. “This, viewed as a battleground, was simply infernal,” a Union soldier later said. Grant’s infantry could not fully deploy, his cavalry could not effectively maneuver, and his artillery had few clear targets. “It is impossible to conceive a field worse adapted to the movements of a grand army,” a Union officer lamented—which is exactly why Lee hit them there.

For two days, the two armies drove each other through the forest in a desperate back-and-forth contest. The woods burned around them.

Then, on May 7, Grant did something no other Federal commander had done before following a mauling at Lee’s hands: instead of withdrawing, he ordered the Army of the Potomac to maneuver past the Confederates. “There will be no turning back,” he had said the day before—and his men cheered wildly when they saw he meant to keep his word.

Grant ordered the army toward Spotsylvania Court House, where the open ground was more conducive for a knock-out battle. The village also provided the inside track to Richmond. Although Grant didn’t care about the Confederate capital, he knew Lee had to defend it, so by moving on the city, Grant could force a confrontation.

Lee’s smaller army—quicker and more maneuverable—got the jump on Grant and beat him to the Court House. More fighting ensued. Major assaults on May 8, 10, and 12 achieved varying degrees of success, but time and again, Lee staved off disaster. Grant, unperturbed, vowed to “fight it out along this line if it takes all summer.”

In the midst of the grapple, the muggy weather broke. Rain. Quagmire. Misery. “The whole country is a sea of mud,” a Federal artillerist wrote. One of Grant’s aids lamented that “the men can secure no proper shelter and no comfortable rest.”

On May 14, Grant tried to outmaneuver Lee once more by sliding to the left. Once more, Lee countered.

When Grant arrived at the Brock Road/Plank Road intersection and made it clear that he intended to push on rather than turn back, Federal soldiers cheered wildly. (loc)

The armies probed, shifted, fortified. The men forged onward, trudged, slogged. Tension mounted. Exhaustion deepened. Nerves frayed.

“It was a curious study to watch the effect which the constant exposure to fire had produced on the nervous systems of the troops,” one Federal officer observed. “Their nerves had become so sensitive that the men would start at the slightest sound, and dodge at the flight of a bird or the sight of a pebble tossed past them.”

Grant’s tenacity and Lee’s adaptability seemed the perfect match. For more than two weeks, the men had been in nonstop motion, marching, fighting, and maneuvering—virtually all of it while in close contact with the enemy.

“The days have been clear of late, not very warm,” said a Federal artillerist after the rain cleared on May 16, “but there is a heavy fog every night, which keeps things in a state of chronic dampness and nastiness… . We are all getting used to this wretched life now. I am astonished to find how little sleep I can get along with, when kept up by constant excitement.”

No one thought it could last, though, least of all Army of the Potomac commander George Gordon Meade. “[I]t is hardly natural to expect men to maintain without limit the exhaustion of such a protracted struggle as we have been carrying on,” he wrote his wife.

Combined, the two armies had lost some 60,000 men since the opening of the campaign. “If it required the loss of twenty thousand to rob us of six thousand, [Grant] was doing a wise thing, for we yield our loss from an irreplaceable penury, he from super-abundance,” one Confederate noted ruefully. “[U]ltimately such bloody policy must win.”

Confederate Lt. Gen. James Longstreet—Lee’s “Old Warhorse” (top)—had arrived on the Wilderness battlefield in the nick of time to save the Confederate army from disas...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- List of Maps

- Acknowledgments

- Touring the Battlefield

- Foreword

- Prologue

- Chapter One: The Campaign

- Chapter Two: Hancock’s March

- Chapter Three: The Fog of War

- Chapter Four: Leaving Spotsylvania

- Chapter Five: The Night March

- Chapter Six: “Wherever Lee Goes . . .”

- Chapter Seven: Before the Storm

- Chapter Eight: The Battle for Henagan’s Redoubt

- Chapter Nine: The Battle of Jericho Mills

- Chapter Ten: Lee’s Council of War

- Chapter Eleven: At Mt. Carmel Church

- Chapter Twelve: Marching into the Trap

- Chapter Thirteen: The Battle of Ox Ford

- Chapter Fourteen: Strike Them a Blow

- Chapter Fifteen: Stalemate

- Appendix A: The Battle of Wilson’s Wharf

- Appendix B: The Battle of Milford Station

- Appendix C: The Eye of the Storm

- Appendix D: Lee’s Engineer: Martin Luther Smith

- Appendix E: Preserving North Anna: A Personal Battlefield Journey

- Appendix F: Preserving North Anna: The Art of the Battle

- Order of Battle

- Suggested Reading

- About the Author