![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction

Context

To all appearances, in the summer of 1941, Germany, led by its Führer, Adolf Hitler, was simply replicating its brilliant military feats of the recent past, only this time against the mighty Soviet Union. Two years before, in September 1939, the fledgling German Wehrmacht had vanquished Poland’s army in just short of one month and cynically divided the country between itself and the Soviet Union. Just over one year before, in April 1940, the Wehrmacht invaded and occupied Demark and Norway in a matter of days and followed up that success by invading the Low Countries and France in May. Once again proving the superiority of Blitzkrieg [Lightening] war, the Wehrmacht, spearheaded by its vaunted panzer and motorized forces and its dreaded Stuka dive bombers, defeated the French and British Armies, shattering the former and forcing the latter to evacuate its forces from the European continent at Dunkirk. An astonished world then watched as German forces captured Paris and forced the French government to sue for peace after a mere seven weeks of war. Finally, in April 1940, a small portion of Germany’s Armed Forces conquered Yugoslavia in only four days and Greece in a matter of weeks.

Given the defeats Germany inflicted on Europe’s most accomplished armies, when Hitler’s forces invaded the Soviet Union on 22 June 1941, few, if any, expected the Soviet Union’s Red Army to be able to survive a conflict with the Wehrmacht, which, by now, was recognized as Europe’s most accomplished armed force. In fact, when he planned Operation Barbarossa, Hitler’s premier assumption was that the Soviet Union, led by its ruthless Communist dictator, Josef Stalin, would inevitably crumble if the Wehrmacht could defeat and destroy most of its peacetime Red Army in the Soviet Union’s western border regions, that is, in the 250-450-kilometer-wide belt of territory between the Soviet Union’s western border and the Western Dvina and Dnepr Rivers.

Hitler believed this assumption was correct for three principal reasons. First, the Red Army had performed dismally in its so-called “Winter” War with Finland from November 1939 to March 1940. After experiencing embarrassing defeat in the first stage of this war, the Soviet Union achieved limited victory in the second stage only by the application of sheer brute force. Second, after Stalin consolidated his power in the Soviet Union during the first half of the 1930s by brutally purging all of his potential political opponents, in 1937 and 1938, he purged the Soviet Armed Forces’ officer corps, killing or imprisoning thousands if not tens of thousands of officers. This left the remainder of the Red Army’s officer cadre commanding at levels far above their actual capabilities and devoid of initiative out of fear lest they suffer fates similar to their purged colleagues. Third, and most important, Hitler reasoned that, if his Wehrmacht could advance 300 kilometers in just under 30 days to defeat the Polish Army, 320 kilometers in about seven weeks to defeat the Armed Forces of France and the Low Countries, and 200-300 kilometers in about two weeks to defeat Yugoslavia and Greece, it could certainly smash the Red Army and penetrate 250-450 kilometers to reach the Western Dvina and Dnepr Rivers in four to five weeks. Since Moscow, Stalin’s capital city, was only 450 kilometers beyond, it was reasonable for Hitler to believe that, if his assumption proved correct, the Wehrmacht could indeed reach the Soviet capital within three months after the beginning of the German invasion. That would have brought the advancing Wehrmacht to the gates of Moscow sometime in October, well before the onset of the Russian winter.

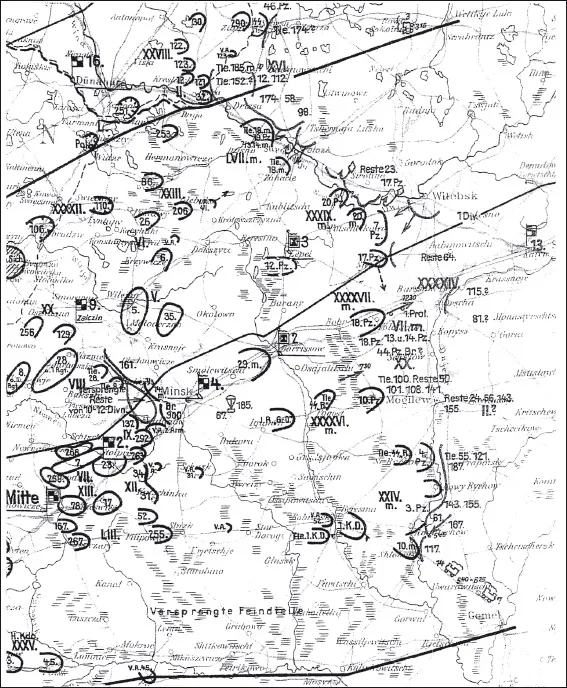

Map 1. Army Group Center’s Situation Late on 7 July 1941

The man most responsible for seeing to it that the Wehrmacht validated Hitler’s assumptions was Field Marshal Fedor von Bock, the experienced commander of German Army Group Center, the strongest of three German army groups conducting the Barbarossa invasion. Bock’s army group, which included two of the German Army’s [Heeres] four powerful panzer groups, was to invade the Soviet Union from eastern Poland and advance rapidly eastward along the Western (Moscow) axis to destroy the Red Army’s forces in the border regions, seize the cities of Minsk and Smolensk, and then drive straight eastward to capture the Soviet capital at Moscow.

Army Group Center’s Achievements, 22 June-6 August 1941

Attacking by surprise on 22 June 1941, Bock’s army group fulfilled all of Hitler’s expectations well ahead of schedule. During the first ten days of Operation Barbarossa, Army Group Center’s forces, spearheaded by its Third and Second Panzer Groups, penetrated, encircled, and destroyed three Soviet armies (the 3rd, 4th and 10th) outright, in the process killing or capturing over half a million Red Army troops and seizing the city of Minsk. Thereafter, in a period of just over one week, the panzers of the army groups’ multiple motorized corps reached the Western Dvina and Dnepr Rivers in the broad sector from Polotsk southward to Rogachev by 7 July, fulfilling Hitler’s premier assumption in a matter of just over two weeks. Undaunted by its surprise encounter with fresh Soviet armies along the Dvina and Dnepr River lines, Army Group Center nonetheless pushed on toward the east, crossing the two rivers, defeating the five defending Soviet Armies (16th, 19th, 20th, 21st, and 22nd), capturing the city of Smolensk, and encircling another three Soviet armies (16th, 19th, and 20th) in a large pocket north of the city. By capturing Smolensk on 16 July, Bock’s forces had advanced roughly 500 kilometers in 25 days of fighting, by doing so eclipsing the incredibly high rates of advance the Wehrmacht had recorded during its previous campaigns in the West. More important still, Moscow was only 300 kilometers beyond. Based on previous German rates of advance, which amounted to roughly 20 kilometers per day and 140 kilometers per week, allowing for pauses to rest, refit, and resupply, Moscow was only two-three weeks distant.

See Map 1. Army Group Center’s Situation Late on 7 July 1941

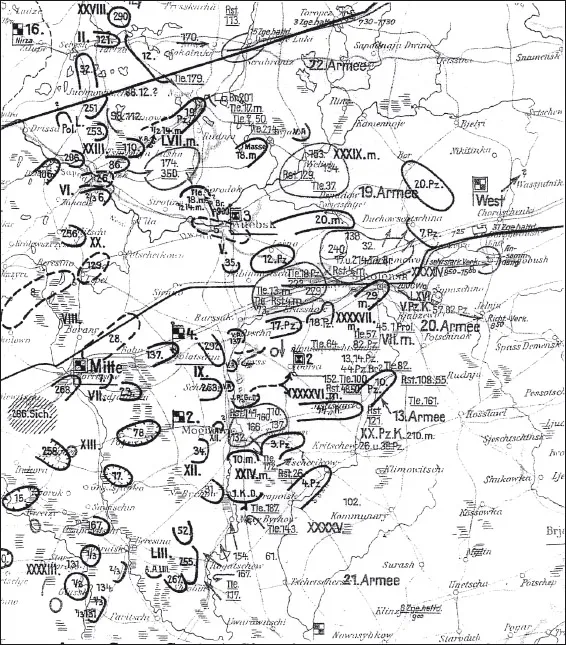

See Map 2. Army Group Center’s Situation Late on 16 July 1941

Although Bock had to halt his army group’s forward progress toward Moscow for about two weeks to defeat and digest the three Soviet armies encircled in the Smolensk region, nevertheless, Bock’s forces capitalized on the pause by attacking and defeating sizeable groups of Red Army forces threatening the army group’s extended northern and southern flanks. In light of the planning guidance Hitler gave to his commanders before the launch of Operation Barbarossa, these successful actions on Army Group Center’s flanks were absolutely necessary prerequisites for any subsequent advance on Moscow. In accordance with the Führer’s instructions, roughly half of the infantry of Field Marshal Günther von Kluge’s Fourth “Panzer” Army and Colonel General Adolf Strauss’ Ninth Army, reinforced for a time by four panzer and motorized divisions, reduced the Smolensk pocket from 16 July through 6 August. While they did so, the bulk of Colonel General Hermann Hoth’s Third Panzer Group and Colonel General Heinz Guderian’s Second Panzer Group manned an “outer encirclement line” northeast and southeast of Smolensk to keep potential Soviet relief forces at bay while their sister formations reduced the pocket. Ultimately, the battles along this “outer encirclement line” pitted nine of Hoth’s and Guderian’s panzer and motorized divisions against five small, newly-formed and hastily-assembled Soviet armies (29th, 30th, 19th, 24th, and 28th), which the Soviet Stavka and Western Front deployed along Army Group Center’s so-called “eastern front,” northeast and east of Smolensk and in the El’nia region southeast of the city.

Map 2. Army Group Center’s Situation Late on 16 July 1941

While heavy fighting raged on along the “outer encirclement line,” the struggle expanded to encompass Army Group Center’s northern and southern flanks. In the north, roughly half of Strauss’s Ninth Army, supported by one panzer division and one motorized division from Hoth’s panzer group, protected the army group’s northern flank by seizing the Nevel’ region. To the south, Field Marshal Maximilian von Weichs’ Second Army, supported by two panzer divisions and one motorized division from Guderian’s Second Panzer Group, pushed Soviet forces arrayed along the army group’s southern flank back toward the Rogachev and Zhlobin region and eastward to the Sozh River line. Finally, during the first week of August, one motorized corps of Guderian’s panzer group struck at Soviet forces attacking northward from the Roslavl’ region toward Smolensk. In a brief fight lasting only six days, Guderian’s forces encircled and destroyed the bulk of seven Red Army divisions subordinate to Soviet Group Kachalov. Nor were the lessons of Strauss’ and Guderian’s easy victories on the army group’s northern and southern flanks lost on Hitler. In fact, as the Führer adjusted his strategy for victory in the East, he increasingly favored quick and profitable victories on the flanks over what he thought would prove to be bloody and costly frontal assaults against the Red Army where it was strongest, that is, along the Moscow axis.

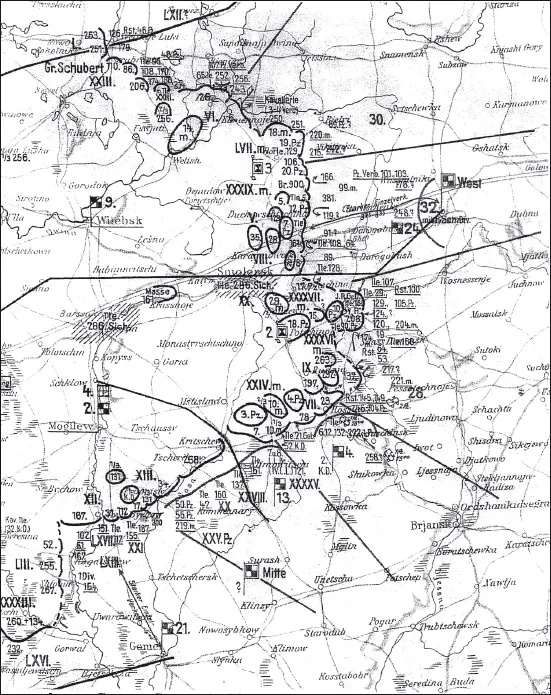

See Map 3. Army Group Center’s Situation Late on 6 August 1941

Thus, by the end of the first week in August, Hitler, his Armed Forces (OKW) and Army High Command (OKH), and Field Marshal Bock had every reason to be proud of the victories Army Group Center achieved during the first six weeks of Operation Barbarossa. During this astonishingly brief period in the wake of its brilliant victories in the border regions, Bock’s army group demolished the Red Army’s second strategic echelon defenses along the Dvina and Dnepr Rivers, captured Smolensk, the historical eastern gateway to Moscow, and killed, wounded, or captured over 600,000 Red Army troops, most of them at the expense of the Red Army’s Western Front, now commanded by Marshal of the Soviet Union Semen Konstantinovich Timoshenko. Enthusiastic over this seemingly Herculean feat, Hitler, most of his senior commanders, and German soldiers expected nothing short of a rapid German victory, secured by a Blitzkrieg-style triumphant advance on Moscow.

Army Group Center’s Problems by 6 August 1941

Despite the many victories the Wehrmacht won in Army Group Center’s sector during the first six weeks of war, there were several ominous indicators that future victories might not prove to be as easy as most Germans anticipated. The first and most important indicator was the utter collapse of Hitler’s premier assumption regarding the war, specifically, the belief that the Soviet Union would collapse if the Wehrmacht could destroy the bulk of its Red Army west of the Western Dvina and Dnepr Rivers. By 10 July this assumption proved patently incorrect. Although Bock’s army group destroyed three of the Soviet Western Front’s four field armies (3rd, 4th, and 10th) by the end of June when his forces reached the two rivers on 7 July they discovered five more Soviet armies (16th, 19th, 20th, 21st, and 22nd), which, although weak, were still willing and able to fight. Four weeks later, after encircling and decimating three of these five armies (16th, 19th, and 20th) in the Smolensk region by 6 August, Bock was chagrined to find his army group facing yet another “row” of five new Soviet armies (24th, 28th, 29th, 30th, and Group Iartsevo), which rose phoenix-like from Soviet rear area to supplement 13th, 21st, and 22nd Armies still intact in the field. Furthermore, unknown to German intelligence, still another row of Soviet armies was forming further to the rear (31st, 33rd, and 43rd). Most ominous of all, although the Germans fervently believed this process would end after the fighting in the Smolensk region, in fact, it would continue unabated to year’s end.1

Map 3. Army Group Center’s Situation Late on 6 August 1941

The second indicator already disturbing senior German military leaders in early August was the reality that war in the East differed fundamentally from previous wars in the West in several important respects. First and foremost, combat during the first six weeks of war demonstrated that “eastern kilometers” differed fundamentally from “western kilometers.” Specifically, the under-developed road system and the different gauge track employed in the Soviet railroad system made movement exceedingly difficult. While the largely dirt-surfaced roads turned into impenetrable quagmires during periods of heavy rain, the varying gauge of the railroads made it necessary for the Wehrmacht to reconstruct the railroads as they advanced eastward. The ensuing strain on German logistics, coupled with the necessity of rebuilding blown up bridges, made logistical resupply of advancing forces a problem of major importance. Making matters worse, the panzer and motorized divisions of Bock’s two panzer groups, which inevitably operated far forward of Army Group Center’s main forces, suffered most from these problems. In short, fuel shortages severally restricted the capabilities of these forces to operate in the enemy’s depths. Finally, although it would not have a major impact of the Wehrmacht’s operational capabilities until October 1941, the Russian climate, with its sharply differing seasonal weather conditions, would only compound the German Army’s other logistical problems.

Operationally, and to a lesser extent tactically, because of these logistical impediments, the Wehrmacht proved unable to conduct sustained Blitzkrieg-style operations in such a vast and underdeveloped theater of military operations. Thus, another key German assumption regarding Operation Barbarossa’s prospects for success, specifically, that Blitzkrieg-style war which produced easy victory in the West would result in equally spectacular victory in the East, proved unfounded. As a result, after this assumption proved to be false by mid-July, thereafter, the Wehrmacht was compelled to conduct virtually all of its offensive operations in ad hoc fashion, by advancing in distinct offensive “spurts,” followed inevitably by extended periods of time necessary to rest, refit, and resupply its forces.

A third indicator of still greater difficulties in the future regarded German assumptions about the Red Army itself, in particular, the attitudes, morale, and combat capabilities of its officer corps and common soldiers. In this regard, based on the Red Army’s previous performance in Poland in September 1939 and in Finland from November 1940 to March 1941, the Germans assumed neither Soviet officers nor Red Army soldiers would stand and fight when confronted by German tanks, Stuka aircraft, and well-trained and battle-hardened German Landsers. Although based in part on objective analysis, much of this assumption was firmly rooted in Nazi ideology and racial theories, which maintained that, inherently, racially-inferior Slavic officers and soldiers could not or would not fight on a level commensurate with their superior German counterparts. A corollary to this assumption was that Red Army officers and soldiers, if not whole segments of the Soviet Union’s population (Belorussians, Ukrainians, and the many peoples of the Caucasus region), detested both Stalin and the Communist system. Therefore, reasoned the Germans, when given the opportunity to do so, these officers and soldiers would lay down their arms in surrender or simply desert and disappear into the Russian countryside.

By early August, however, these assumptions too proved to be false. Although Red Army soldiers did indeed surrender or defect by the hundreds (but far fewer officers), tens if not hundreds of thousands more fought, often in suicidal fashion, and died in the face of German invasion so that hundreds of thousands more would prevail. Thus, despite their enthusiasm over the army’s many victories, many German officers and soldiers had just cause to question just how easy future victory would be.

Soviet Problems, 22 June-6 August 1941

All of the Germans’ problems notwithstanding, the political and military leadership of the Soviet Union and the Red Army’s officers and soldiers also faced unprecedented trials and daunting challenges during July and the first week of August 1941. By every standard of measure, the July and early August fighting produced catastrophe after catastrophe and a seemingly endless series of major crises for the Red Army. The starkest and most unsettled reality was that the Red Army lost up to a third of its peacetime compliment of officers and soldiers during the first six weeks of war, perhaps as many as 1.5 million officers and soldiers, a figure that rose inexorably to almost 3 million men by the end of August 1941. Because the vicious fighting during this period deprived the Red Army of its best trained soldiers, increasingly throughout the summer, it would have to make do with partially-trained reservists and largely untrained conscripts raised from across the vast extent of the Soviet Union. This left the Red Army’s senior command cadre with no choice but to educate and train its junior officers and soldiers while combat went on with ...