![]()

1 · INTRODUCTION:

NETWORKS AND HUMAN BEHAVIOR

The More Things Change

“In Globalization 1.0, which began around 1492, the world went from size large to size medium. In Globalization 2.0, the era that introduced us to multinational companies, it went from size medium to size small. And then around 2000 came Globalization 3.0, in which the world went from being small to tiny.”

— THOMAS FRIEDMAN, INTERVIEW IN WIRED

(AUTHOR OF THE WORLD IS FLAT)

On December 17, 2010, Mohamed Bouazizi, a twenty-six-year-old street vendor in the dusty small city of Sidi Bouzid in central Tunisia, lit himself on fire. He did so as a desperate statement of outrage at the tyrannical government that had ruled Tunisia for more than two decades and repeatedly crushed any opposition. His family had long been outspoken against the government and he found himself regularly harassed by the local police. That morning, the police publicly humiliated him and confiscated his day’s produce. Mohamed had borrowed the money to buy his produce, and its loss was the last of many straws. Mohamed drenched himself in gasoline and burned himself alive in protest.

Decades ago, the several-thousand-person protest that quickly followed would have been the end of the story. Few outside of Sidi Bouzid would have even been aware that anything happened. However, videos of the aftermath of Mohamed Bouazizi’s self-immolation were impossible to contain and were quickly shared via social media and reported widely. News of the Tunisian and other governments’ oppression had already been spreading after confidential documents appeared weeks earlier on WikiLeaks. The Arab Spring that would follow was enabled by and coordinated via social media such as Facebook and Twitter as well as cell phones.1

Although the methods of communication were modern, ultimately it was a network of humans spreading news and outrage. What was new was how widely and quickly news could spread, and how people were able to coordinate their responses. But understanding what happened still boils down to understanding how news spreads between people and how their behaviors influence each other.

The size and ferocity of the resulting Tunisian protests toppled the government by mid-January. The insurgency had also spread to neighboring Algeria, and over the next two months erupted in Oman, Egypt, Yemen, Bahrain, Kuwait, Libya, Morocco, and Syria, and even Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and the United Arab Emirates. The successes and failures of the Arab Spring are open to debate. But the swift proliferation of protests throughout that part of the world was not only unprecedented but highlighted the importance of human networks in our lives.

As dramatic as recent changes in human communication have been, as Thomas Friedman’s quote above indicates, the world has shrunk many times before—in the wake of: the printing press, the posting of letters, overseas travel, trains, the telegraph, the telephone, the radio, airplanes, television, and the fax machine. Internet technology and social media are only the latest chapter in the long history of changes in how people interact, at what distance, how quickly, and with whom.

Yet even as networks of interactions between humans change, much about them is enduring and predictable. Understanding human networks, as well as how they are changing, can help us to answer many questions about our world, such as: How does a person’s position in a network determine their influence and power? What systematic errors do we make when forming opinions based on what we learn from our friends? How do financial contagions work and why are they different from the spread of a flu? How do splits in our social networks feed inequality, immobility, and polarization? How is globalization changing international conflict and wars?

Despite their prominent role in the answers to these questions, human networks are often overlooked when people analyze important political and economic behaviors and trends. This is not to say that we have not been studying networks, but instead that there is a chasm between our scientific knowledge of networks as drivers of human behavior and what the general public and policymakers know. This book is meant to help close that gap.

Each chapter shows how accounting for networks of human relationships changes our thinking about an issue. Thus, the theme of this book is how networks enhance our understanding of many of our social and economic behaviors.

There are a few key patterns of networks that matter, and so the story here involves more than just one idea hammered home. By the end of this book, you should be more keenly aware of the importance of several aspects of the networks in which you live. Our discussion will also involve two different perspectives: one is how networks form and why they exhibit certain key patterns, and the other is how those patterns determine our power, opinions, opportunities, behaviors, and accomplishments.

Billions Upon Billions of Networks

“Life is really simple, but we insist on making it complicated.”

— UNKNOWN2

Carl Sagan, in his famous book on the cosmos, talked of the “billions upon billions” of stars that exist in our universe. The number of stars in the observable universe has been estimated to be on the order of three hundred sextillion: 300,000,000,000,000,000,000,000—a number that sounds fictitious, like a zillion or a gazillion. If you are anything like me, it makes you feel small and insignificant, and in awe of nature.

The amazing thing is that this is a tiny number compared to the number of different networks of friendships that could potentially exist among a small community—say a classroom, a club, a team, or the workers at a small company. Impossible, you say? How can this be so?

Consider a community of 30 people—for instance, all the parents of children in a class at school. Pick any one of our 30 parents—say Sara. Let us consider her friends within this community to be the people with whom she regularly talks or could depend upon to help her out. There are 29 other people with whom Sara could be friends. The second person—say Mark—not counting his potential friendship with Sara, could be friends with any of the 28 others. If you keep adding these up, the number of pairs of people in our small community who could be friends with each other is 29 + 28 + 27 + . . . + 1 = 435. Although that does not sound like too many possible friendships, it translates into a huge number of possible networks.

For example, if our community were completely dysfunctional, nobody would be friends with anyone else; we would have an “empty” network, devoid of relationships. So, all 435 possible friendships would be absent. If our community were completely harmonious, we would see the opposite extreme—a “complete” network in which every person would be friends with every other. There are many networks between these extremes. Maybe the first pair of people are friends with each other, but the second pair are not; then maybe the third and fourth pairs are friends, but not the fifth and sixth and so on. To find the total number of networks of friendships, we note that each possible friendship could either be switched “on” or “off,” and so there are 2 possibilities for each friendship. Thus, the number of possible networks is 2 × 2 × · · · × 2, with 435 entries. Doubling a number 435 times results in a 1 followed by 131 zeros—the sextillions previously mentioned have just 23 zeros.3 So: sextillions of sextillions of sextillions of . . . networks—many times the number of stars in the universe, in fact, many orders of magnitude larger than the estimated number of atoms in the universe!4

Even with just 30 people, there are far too many networks to label in any systemic way. In classifying animals, when someone says “zebra” or “panda” or “crocodile” or “mosquito” we know what they are talking about. Except for a few special classes, we really cannot do that with networks. This does not mean that we should throw up our hands and say that social structure is too complicated to understand.

There are also characteristics that allow us to classify and distinguish animals: Do they have a spine? How many legs do they have? Are they herbivores, carnivores, or omnivores? Do they have live births? How large are the adults? What type of skin do they have? Can they fly? Do they live underwater? . . . When classifying networks we can identify critical characteristics too. For example, we can distinguish networks by the fraction of relationships that are present, whether those relationships are evenly distributed among the people involved, and whether we see certain segregation patterns. Moreover, these patterns will enable us to understand such issues as economic inequality, social immobility, political polarization, and even financial contagions.

Describing networks for our purpose of understanding human behavior is manageable for several reasons. First, a few primary features of networks yield enormous insight into why humans behave the way they do. Second, these features are simple, intuitive, and quantifiable. Third, human activity exhibits regularities that lead to networks with special features: it is easy to distinguish a network formed by humans from one in which the links are just formed randomly without any dependence on the other links around them or which nodes they connect.

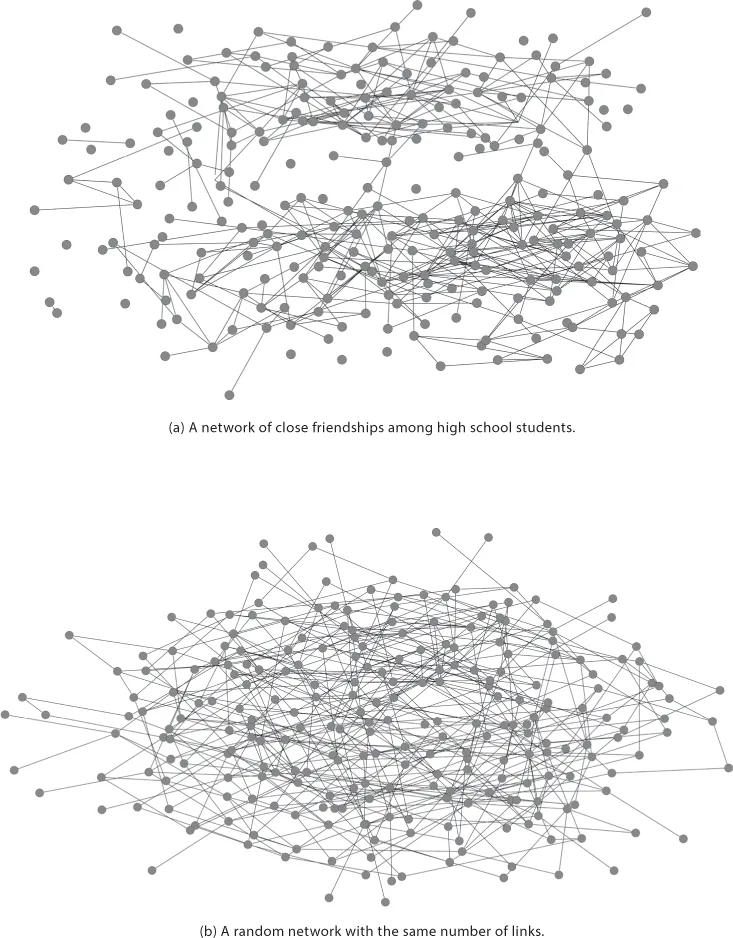

As an example, consider the two networks in Figure 1.1. The network in panel (a) is a network of close friendships between high school students (details about this network appear in Chapter 5). The network in panel (b) has the same number of nodes and connections, but with the connections placed completely randomly by a computer.

So what is so different about the two networks? You can see a couple of things just by looking carefully. One is a sad fact of high school: there are more than a dozen students who have no close friends, while the random network has all nodes connected. The second more striking and general feature of the human network is that it is highly segregated. The students in the top part of the network are very rarely friends with the students in the bottom part of the network. The random network has links going in all directions.

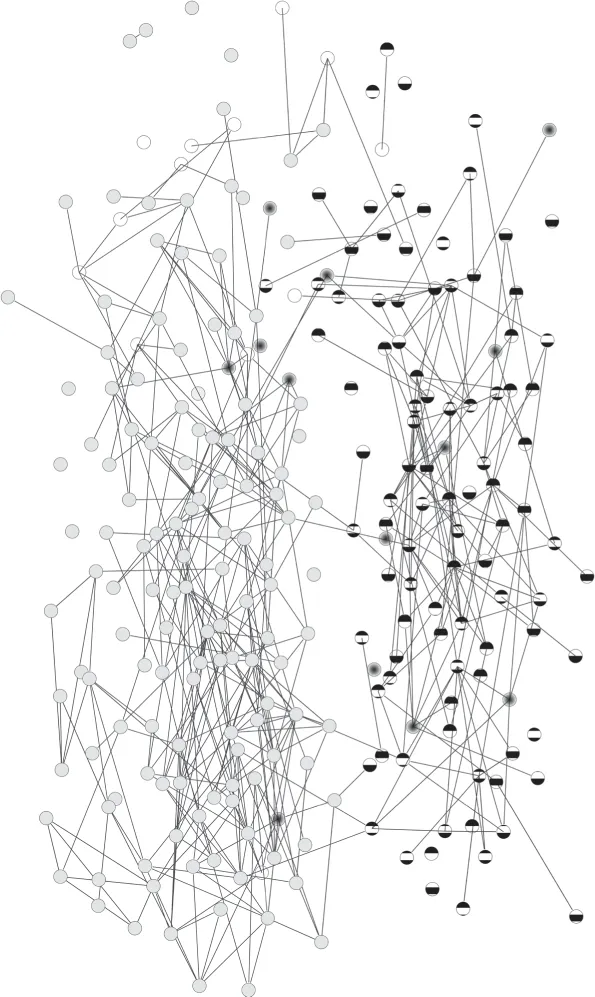

The split in the network gets much easier to see, and more telling, when I add the races of the students in the high school, as in Figure 1.2.

Such divisions are one key feature of human networks, among several, that figure prominently in what follows. Why we form networks that have such features has some obvious explanations as well as some subtle ones, as we shall see. Ultimately, we care about our networks and their features because of their impact, and so by the end of this book you should know, for instance, why having divisions such as that in the high school network above profoundly impacts decisions to go to college, but yet has almost no impact on contagion of a flu.

Figure 1.1: A human network and a random network.

Figure 1.2: The High School Network Coded by Race. The nodes with bold stripes are self-identified as being “Black,” the nodes with gray fill are “white,” and the few remaining nodes are either “Hispanic” (center dot fill) or “Other/Unknown” (blank).5

Part of what makes the science of networks such fun, beyond the fact that it is so immediately important in all of our lives, is ...