![]()

CHAPTER ONE

I sat fascinated at a world I’d never known existed.

MY MOTHER TOLD ME that when I was young that everyone and everything was just a thing, I was forever talking about ‘Bijou’. My parents paid little attention. There was a Bijou Theatre they went to, and they thought perhaps that was what I had in mind. But as I grew older, being an only child, I would wander off by myself down to the beach and scuff the water with flat stones. It was then I knew that Bijou was my dog, my friend and my invisible companion. He’s been with me ever since.

As I grew older I learned to make the stones skip far out into the Pacific – then I’d whisper, ‘Look, Bijou, that one went all the way to America.’

Bijou was a great comfort to me when my father’s voice awakened me at night; I could hear it plainly upstairs in my bed. Then I’d hear Mother say, ‘If you would drink like a Purdue you would drink like a gent, but you drink like a Kelly.’

My father would shout again, ‘What’s wrong with the Kellys? My grandfather was architect to the Duke of Atholl . . .’ And on and on it went, far into the night.

Orry was my given name. I was born in 1897. My father was a Manxman, from the Isle of Man, and I was named for a Danish king who had conquered the island centuries ago.

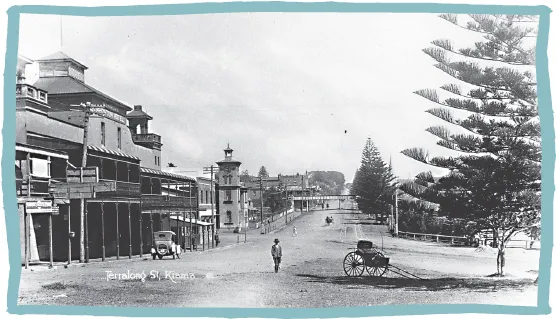

In the seaport town of Kiama, where I lived, I was considered ‘bush’ – the term used for those born in the country. I didn’t have a poor childhood. I had a nurse. Socially, we didn’t belong in the top drawer of the highboy with the dress shirts, but neither did we fit in with the socks in the lower drawer; we belonged somewhere in the middle, for we were in ‘trade’. The sign over my father’s shop read: ‘WILLIAM KELLY, Merchant Tailor’, and at home I remember much talk of importing worsteds, flannels, serges and tweeds.

My mother was a Purdue, and for this reason I was allowed to attend Miss Ingall’s private school, where little boys and girls were taught manners, given lessons in ballroom etiquette and shown the steps of the polka. In dancing class I liked best the shiny dancing pumps with their flat bows.

Among my earliest recollections, I remember running home from school, bawling my eyes out, my classmates shouting after me: ‘You’re bankrupt, you’re bankrupt, your old man’s bankrupt!’ I didn’t know what the word meant, but I was sure it was something awful. And my mother thought so too. With the help of her brother-in-law, a contractor, Mother was able to build some income property on her Purdue-owned land. To economise, I was sent to a publicly supported school. It took years, but eventually Mother paid off every penny of my father’s debts.

My father didn’t drink so much after the bankruptcy, but he retreated from the annoyances of life by immersing himself in the culture of carnations. He won many blue ribbons at the horticultural shows with his unique ‘Ringer’ – a hybrid he developed – a white carnation, its petals edged with violet. He also hybridised another prize carnation – a shocker in shocking pink, which he named ‘Orry Kelly’.

When I was seven, my mother took me to Her Majesty’s Theatre in Sydney to my first pantomime, Dick Whittington and His Cat. The part of Dick was played by a beautiful lady with a long quill in her cap. She wore a leather jerkin, high-laced suede boots, and carried a swag across her shoulder. At her side was a black cat. There was a demon king, and a devil who came up from a trapdoor with a flash of lightning. I liked best the transformation scene: Beginning with an exterior of the palace, a series of scrims lighted up. The audience was taken through a series of long corridors, finally reaching the Throne Room. When the panto ended and the house lights went up, I sat as in a dream. Mother had trouble making me budge.

The following Christmas I got a miniature stage set. Not liking the scenery, I set about designing my own. Between the proscenium arch I glued two curtains – one red, the other gold. I made reflectors for the footlights out of tinfoil from cigarette boxes. From the same boxes I collected coloured photos of London’s famed musical comedy performers, the Gaiety Girls.

Our rambling two-storey house had extra rooms built on downstairs, and there was a small section with no roof where wonderful ferns were planted. We had a huge garden, which took up about three house plots; among the flowerbeds were many fruit trees, a grape arbour and a small fish pond.

Dressed to impress in the front row (second from right) at the Kiama Church of England Sunday School concert in 1905.

I played with my toy theatre-land in the pigeon loft of a two-storey building behind the house. Saturdays I spent most of the day making additional figures out of cardboard. I dressed the Queen in a long red robe made out of some velvet scraps I’d nicked from Mother’s sewing room, but I found coloured crinkled paper much more to my liking because, with a little glue, the costumes could be fastened more easily to the painted cut-outs. My Lady’s Companion wasn’t much use since the scissors wouldn’t cut, and I couldn’t thread the needles, but the coloured silk was useful. I used tiny candles to light up the stage windows in the transformation scene.

One Saturday, right after lunch, I had almost finished the transformation scene when along came Father in his striped pants and swallow-tail coat. He had been gardening. He said something to me about a boy, seven years old, playing with dolls. He broke the cardboard figures and kicked the Lady’s Companion to smithereens. Taking me outside, he put a huge wheelbarrow in my hands and ordered me to go to the Point and fetch manure for his garden.

About five miles outside Kiama lived the wealthy Fuller family. Early settlers, their huge tracts of land included their own railway station. The oldest son, George, had been sent home to Oxford to finish his education. He was one of Sydney’s leading barristers.

I knew that on Saturdays the Fuller family drove to Kiama in their phaetons and broughams, and played tennis at a private court that was located on the point jutting out from our house. The coachman usually drove the young daughters, who went to my dancing class, in their dog cart. By the tennis courts was a section where horses grazed, and it was to this pasture my father had ordered me. I was afraid the girls would see me with my wheelbarrow full of manure.

It took most of the afternoon to load up. The trip home was long. I kept dodging behind trees, hiding from people driving in their traps and sulkies. I was almost home when I caught sight of the Fuller girls approaching in their dog cart. In my excitement, pushing my heavy load on the run towards a nearby fig tree, my wheelbarrow overturned. And so did I. I heard shrieks of laughter from the girls as they passed. I rolled over, away from the roadside, and cried with humiliation. When I arrived home I looked terrible, and smelled worse.

At the far end of the Point, below the lighthouse, my father had built wonderful natural swimming baths surrounded by irregular lava rock. It was named for him. This was my favourite playground.

My father was a great diver and champion plunger, and was once given a gold medal for diving into the shark-infested harbour to plug a hole in a cargo ship. One summer I had saved a boy who was caught in a rip-tide, and for this was presented a bronze medal. In no time at all the medallion turned dark brown, much like an Australian penny. The engraved inscription meant nothing to me, so I threw it away. I thought they should have given me a gold one like my father’s.

After my first taste of the theatre at seven years old. I was hooked. When the house lights went up, I sat as if in a dream.

After incidents such as that, my cobbers would decide I was fair dinkum or a good sport. Other times I would let my mates down on a Saturday afternoon by going off to paint a seascape with my teacher, Walter Cocks. Again, I was the odd one.

The poorer kids earned sixpence by riding the mail to Jamberoo, about five miles away. I had no pony. I offered to carry the heavy leather bag of mail for nothing. They often were short of saddles at the livery stables, but no matter, I’d ride bareback; cantering over the hills was great fun – until the cheeky kids beat me up for scabbing.

I was really the last hope on the football team. Although I had no strength in my arms, I could run with the best of them. I also played cricket, until a cricket ball broke my nose.

Mother made me study piano. I could play the melody but had little control over my left hand. After rapping my knuckles for six years Mother said, ‘You’ll never get anywhere in life without bass.’ That ended the piano lessons. At the age of twelve I started to study painting professionally. Endless years of school followed.

When I turned seventeen and still couldn’t pass my exams, Mother decided to send me to Sydney for additional studies. She said, ‘You must matriculate – pass your banker’s exams. You will mix with gentler people and, who knows, one day you may end up as Manager.’ I realised that Mother was not without a bit of snobbery in her make-up.

With my schoolmates’ farewells and shouts of ‘coo-wee’ ringing in my ears, I was sent to live with my Aunt Em in Parramatta, my mother’s birthplace, about three-quarters of an hour’s train ride to the technical college in Sydney.

The Grand Opera House was close by the Sydney railway station. The pantomime had been running for several months, and I found myself hanging around the stage door. With this new pastime I was increasingly late getting home to Aunt Em.

One night, just about dusk, while I was watching the show people entering the stage door, a beautiful red-headed girl passed me on the street. She turned and smiled. I decided she must be an actress, for it was obvious she hadn’t been able to remove all the make-up around her eyes. This was my chance to meet and talk to a real Sydney actress! I followed her. At the corner she crossed the street and walked towards Surry Hills, a cheap section of town. She waited for me by an alley and seemed rather vague when I asked her about the theatre. Before I knew it, we were in a dark doorway. There was some talk of money. I was physically excited. Luckily I had bought a season train ticket, because she took four shillings – all I had in my pocket. She also took my virginity.

She took four shillings . . .

She also took my virginity.

Somehow, I got through my school examinations and went to work in the Bank of New South Wales. But my mind was never on my desk. I loved the theatre. During lunch hour I would dash uptown to audition for shows going into rehearsal.

When I turned eighteen, I desperately wanted to enlist, but the Army accepted no one under twenty-one without parents’ consent. But within a year the war ended. Lloyd George assured us there would be a just and honest peace, a phrase which became very popular. There was dancing in the streets of Sydney.

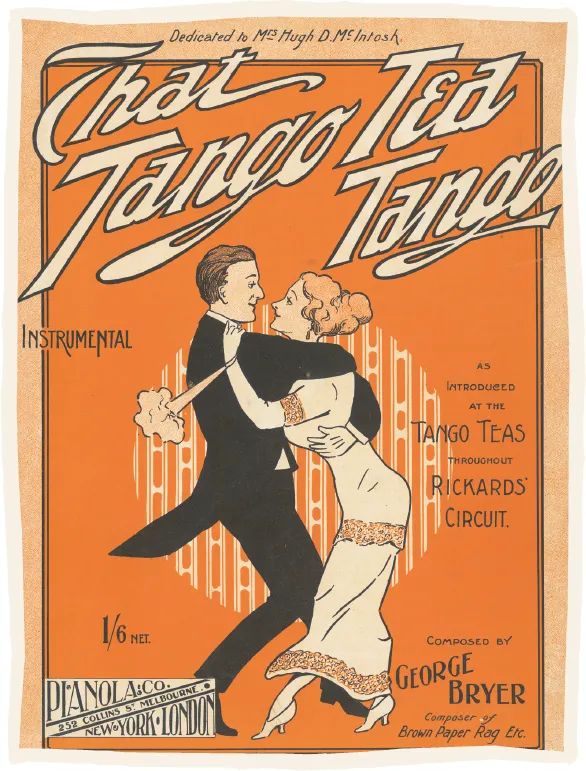

We were launched on a decade of frivolity. Tango Teas were given at the Tivoli Theatre on off-matinee days, and the rich racy set paid top prices for the privilege of dancing on the stage while tea was served in the mezzanine. Jazz bands and wailing saxophones encouraged the younger set to throw away their iron girdles when they danced the foxtrot. Overnight, music became barbaric, its call: freedom of movement. The restricting underpinnings gave way to simple slips, camisoles and lace panties.

During the war the Aussies fraternised with the ‘mademoiselles from Armentières’, as the song said. They returned home to find the girls they left behind wearing flesh-coloured hosiery – before they left, only black lisle, mouse grey, white and pale pink stockings were worn.

The Haymarket branch of the Bank of New South Wales was near the railway station. For over a year I simply went by train to work and returned to my aunt’s in Parramatta. I saw little of Sydney. Then, one day, my audition paid off. I was engaged as a straight man with one line in the bawdy revue Stiffy and Moe.

Thanking my aunt for her kindness, I packed up and moved to Sydney. I found diggings on Hunter Street, in the moist heart of the city with four pubs to every block. I was growing up – I added a couple of years to my age. Sydney took on a new look and so did I.

In my imagination it seemed that Sydney as a whole wore a large over-stuffed Victorian dress. Like most cities, the railway station, the introduction to the traveller, was surrounded by slums. Sydney had one square squalid mile.

Stately Macquarie Street, dignified Potts Point, and other fashionable harbour frontages that were built later, had an Edwardian look. Like their owners, the buildings had a feeling of quality. There was none of the gingerbread and folderol. The people who lived in them wore their clothes well and stood erect, their proud heads held high, with a surety of tilt to their chins. Descendants of the early settlers, they sought adventure in the New World of ‘Down Under’.

Macquarie Street was Sydney’s Mayfair; the lines of the houses were as clean and simple as the lines of the Georgian silver used in the fashionable town flats above the shining offices of professional men whose offices were on the ground floors. Here were located doctors, barristers and solicitors, pioneers’ sons who had been sent home to Oxford and Cambridge for their degrees.

But the hard core of Sydney, the details of its arcades and gingerbread buildings, resembled the heavy Battenburg laces and passementerie trimmings of Good Old Queen Victoria.

Extending from its huge leg-o’-mutton sleeves, like bent elbows, were narrow crooked streets named Bourke, Palmer and Leichhardt. From its frayed skirt and dusty petticoats, other streets, like bandy legs, stretched out to toe the foot of Woolloomooloo. Sitting in the lap of this over-decorated creation was the shining harbour.

The city might have been overdressed, but it had a respectable heart – right in the middle of the shopping district was a park with a kiosk where shoppers lunched and children played. On its left stood Queen’s Square, and to the right stood the huge St Mary’s Cathedral, a block long. Through the iron gates was the Domain, a spreading park covered with a patchwork quilt of flowerbeds. Below the cathedral was Sydney’s toughest section – Woolloomooloo.

Overnight, music became barbaric, its call: freedom of movement. Restricting underpinnings gave way to slips, camisoles and lace panties . . .

Just above the Loo were a series of clay-faced houses, their black sooty chimneys handcuffed together, pointing to the sky. They were built by parolees, the defiant ones. Themselves doomed, they seemed to have purposely planned a way out for their children. At night the streets ended in shadows, making it impossible for the law to track down criminals who darted through a maze of passageways and alleys.

By full moon there was a certain charm, but when the morning sun undressed this voluptuous creature and exposed her tattered and frayed underpinnings, you found this section of Sydney wore dirty drawers. This was the violent part of the town where people lived violently. This was the home of the Sydney underworld.

It was in this section, on Bourke Street, that Alice O’Grady ran her sly grog, a place one could drink on the sly, no matter the time of day. Australian law cal...