![]()

‘Nothing irritates me more than chronic laziness in others. Mind you, it’s only mental sloth I object to. Physical sloth can be heavenly.’

Elizabeth Hurley

I blame the Portuguese.

The word ‘sloth’ has been in the English language meaning ‘slowness’ since the twelfth century at least. Formed in much the same way as ‘width’, meaning ‘wideness’, and often spelt ‘slowth’ or ‘sloath’, it was not used to refer to a particular animal until the mid-fifteenth century when, for reasons that are very unclear, it became used as a collective noun for bears. ‘Sleuth’ was also used by some writers for a company of bears, but as there is no explanation for either a sleuth or sloth of bears, it is unclear which came first or whether one was an error for the other.*

The first reference in English to the animal we now know as sloth by that name was, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, in 1613 in a work by the Anglican clergyman Samuel Purchas entitled Purchas His Pilgrimage: or Relations of the World and the Religions observed in all Ages and Places discovered, from the Creation unto this Present. The book was intended to celebrate the diversity of God’s creation and consisted of a collection of travellers’ tales told to him by sailors. Since Purchas had, by his own proud admission, never travelled as much as 200 miles from Thaxted in Essex, where he was born, the tales were thus necessarily second-hand, but they referred to ‘A Treatise of Brazil, written by a Portugall which had long lived there’. His description of the animals of Brazil included a thoroughly derogatory reference to something the Portuguese called priguiça, which Purchas translates as ‘laziness’:

The Priguiça (which they call) of Brasill, is worth the seeing; it is like a shag-haire Dog, or a Land-spaniell, they are very ougly, and the face is like a woman’s evill drest, his fore and hinder feet are long, hee hath great clawes and cruell, they goe with the breast on the earth, and their young fast to their bellie. Though ye strike it never so fast, it goeth so leasurely, that it hath need of a long time to get up into a tree, and so they are easily taken; their food is certaine Fig-tree leaves, and therefore they cannot bee brought to Portugall, for as soone as they want them they die presently.

Actually it is rather doubtful that Purchas was suggesting ‘sloth’ as the English name for the animal. The above quotation comes from the fourth (1625), hugely expanded edition of his work, which does not refer to the animal as a ‘sloth’ at all. That word appears, as the OED says, in the first (1613) edition, in which he refers to ‘a deformed beast of such slow pace, that in fifteene dayes it will scarse goe a stones cast. It liueth on the leaues of trees, on which it is two dayes in climing, and as many in descending, neither shouts nor blowes forcing her to amend her pace.’ Next to this, in a sidenote, he says: ‘The Spaniards call it (of the contrary) the light dog. The Portugals Sloth. The Indians, Hay.’

Other later writers also give the native American words for the animal as ‘aie’ or ‘aï’, which is supposedly indicative of the cry of a sloth in distress (or female sloth’s mating call – we shall discuss the sounds made by a sloth later). Why Purchas changed his translation of the Portuguese word for the animal from ‘sloth’ to ‘laziness’ is a mystery, but over the course of the seventeenth century, practically every European language had adopted a similar word for the animal. Purchas’s book was a great influence at the time; indeed, his Pilgrimage was the very book that Samuel Taylor Coleridge fell asleep reading before he woke up and wrote his classic poem ‘Kubla Khan’. ‘In Xamdu did Cublai Can build a stately palace,’ as Purchas put it, which Coleridge turned, almost 200 years later, into: ‘In Xanadu did Kubla Khan / A stately pleasure-dome decree.’ Of all the 4,000 pages of Purchas’s great work, this influence on Coleridge must be what he is most remembered for, but his rudeness about sloths was also mimicked by others.

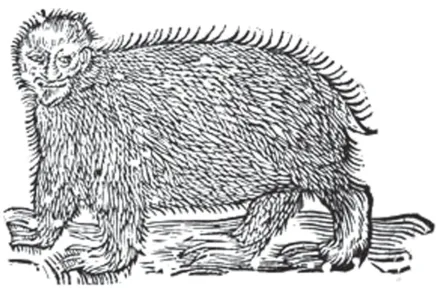

The first to slag off sloths in English was London clergyman Edward Topsell, who called the sloth a bear-ape or Arctopithecus in his History of Four-Footed Beasts (1607):

The sloth according to Topsell.

There is in America a very deformed beast which the inhabitants call Haut or Hauti, & the Frenchmen Guenon, as big as a great Affrican Monkey. His belly hangeth very low, his head and face like unto a childes, as may be seen by this lively picture, and being taken it wil sigh like a young childe. His skin is of an ash-colour, and hairie like a Beare: he hath but three clawes on a foot, as longe as foure fingers, and like the thornes of Privet, whereby he climbeth up into the highest trees, and for the most part liveth of the leaves of a certain tree being of an exceeding height, which the Americans call Amahut, and thereof this beast is called Haut. Their tayle is about three fingers long, having very little haire thereon, it hath beene often tried, that though it suffer any famine, it will not eate the fleshe of a living man, and one of them was given me by a French-man, which I kept alive sixe and twenty daies, and at the last it was killed by Dogges, and in that time when I had set it abroad in the open ayre, I observed, that although it often rained, yet was that beast never wet. When it is tame it is very loving to a man, and desirous to climbe uppe to his shoulders, which those naked Amerycans cannot endure, by reason of the sharpenesse of his clawes.

Actually, Topsell got most of that information from a book called Icones Animalium (1552) by the Swiss naturalist Conrad Gesner, including the part about a sloth given by a Frenchman and kept alive for twenty-six days. In view of this, it seems unlikely that Topsell ever saw a sloth himself. Gesner also acknowledged that his information did not come first-hand, but he did mention, which Topsell chose to ignore, that the claws of a sloth are ‘longer than those of a lion or any of the wild beasts known to us’. Both Gesner and Topsell wrote their books before Purchas, so the latter could be said to have been continuing an already established, let’s-be-rude-to-sloths tradition, which exerted a strong influence throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. The real problem, however, began with Pliny the Elder in the first century AD.

Pliny’s Naturalis Historia was perhaps the first encyclopedia of the natural world. Its thirty-seven books, divided into ten volumes, covered everything from agriculture to zoology, from painting and sculpture to mathematics and bee-keeping, setting a pattern for all other encyclopedists to follow for at least a millennium and a half. Indeed, it was one of the first ancient texts to be published in Europe, appearing in Venice in 1469, which was not long after the invention of the printing press around 1440.

Pliny, however, was not one to be inhibited by a lack of knowledge, and when he was writing of things outside his personal experience, he was liable to conflate truth with myth and observation with hearsay, which is precisely what the early writers on sloths had no compunctions about doing.

The real trouble with sloths was that they were American, while the writing of natural history had been dominated by Europeans from before Pliny to long after Columbus. As we have seen, and shall soon have confirmed by further examples, the leading European naturalists wrote a lot of rubbish about sloths, but science itself was still in its early days. Despite Pliny’s Naturalis Historia, the term ‘natural history’ was not seen in the English language until 1534 (though it had been preceded by ‘natural science’, which included physics and chemistry, since 1425). The word ‘zoology’ did not arrive in the language until Robert Boyle used it in 1663, and ‘scientific method’ was first referred to in 1672. So perhaps we should not be too harsh on these gentlemen for being unscientific, when they did not really even have anything going by the name of ‘science’ to be unscientific about.

Among the earliest writers on New World animals in general and sloths in particular were Gesner (1516–65), whom we have already mentioned, and the Dutchman Carolus Clusius (1526–1609), who was also known as Charles de l’Écluse. They both drew very fanciful pictures of sloths, which confirm that they almost certainly never saw one but were relying on the descriptions of others.

...‘Weariness Can snore upon the flint, when resty sloth Finds the down pillow hard’

William Shakespeare, Cymbeline (1610)

Among those descriptions may well have been the writings of the Spanish historian Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés (1478–1557), who spent many years in Central America, and several Portuguese missionaries and businessmen who wrote of their strange encounters in Brazil. Their various descriptions of sloths read like a game of Chinese whispers with the truth distorted in various different ways. Some seem to have concocted their stories in large part from the writings of others; some seem to have caught some fleeting glimpse of sloths themselves, but to have filled in the details with tales they have been told; while others are so vague or incorrect, it suggests their sloth experience is very limited. The French writers André Thevet (1516?–92) and Jean de Léry (1534–1613), for example, both wrote that sloths have human faces, with Thevet more precisely suggesting that it was the face of a child. Léry pointed out that sloths had never been seen eating, so he concluded that they live on air.

In 1560, the Spanish Jesuit José de Anchieta correctly pointed out that they fed on leaves. He also said they were slower than snails and had a woman’s face. This last point was expanded by Fernão Cardim (1549–1625), who said it was a very ugly face ‘like a badly touched woman’. Unlike the others, who all depicted sloths as walking upright on all fours like other quadrupeds, Cardim said that they walked with their belly on the ground, very slowly. Most confusingly of all, perhaps, the German explorer George Marcgrave (1610–44) gave by far the most detailed and accurate description, complete with measurements, but he reproduced one of Clusius’s drawings of the animal which made it look like a sheep with a human face.

The above descriptions can be found in a 2016 paper entitled ‘Sloths of the Atlantic Forest in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries’ by Danielle Moreira and Sérgio L. Mendes in the Annals of the Brazilian Academy of Sciences. They end the paper with a well thought-out explanation of the reasons behind their findings:

This era of pre-Linnaean zoology was not fundamentally interested in the accurate investigation of nature itself. Instead, it followed the traditions of Renaissance classicism, which emphasizes the author’s stories and knowledge. At that time, faunal records tended to focus on the symbolic meaning of the animals represented, rather than attempting to reflect precisely their zoological reality.

In the eighteenth century, when this era of symbolic nonsense-peddling should have been coming to an end, it was the French who continued ...