![]()

PART I

How We Got Here

![]()

1

IMAGINING THE POST- WAR ORDER

The Atlantic Charter, the United

Nations and global security

The UN was not created to take mankind to heaven, but to save humanity from hell.

Dag Hammarskjöld, UN Secretary-General1

Breakfast in Placentia Bay

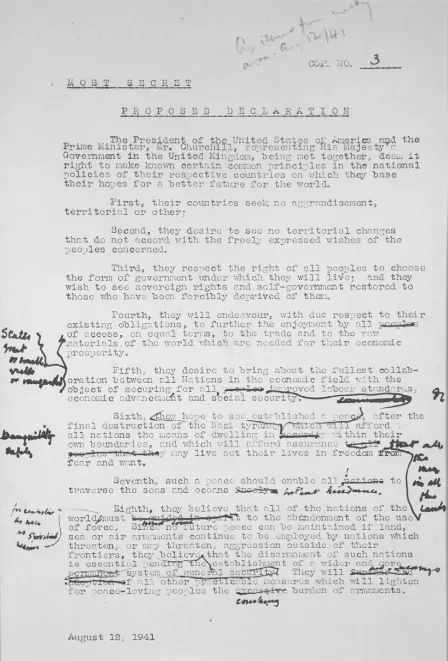

As a young member of the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO), I would sometimes be sent on a nerve-wracking errand to deliver a file to the Permanent Under-Secretary (PUS), who occupied a vast and rather gloomy room in one corner of the building, immediately below the Foreign Secretary. I remember being intrigued by a document that hung on the wall of the PUS’s office. It was a draft of the 1941 Atlantic Charter, with manuscript changes in Churchill’s unmistakeable hand.

When, thirty years later, I became PUS and moved into the same office, I asked the FCO historians to dig up the document and put it back in the same place. I would often look at it and think of the extraordinary circumstances in which it was produced, the way in which it had shaped the landscape of my working life, and the central role my wartime predecessor, Sir Alexander Cadogan, played in its creation.

Cadogan is now a largely forgotten figure, but he had more impact on British policy during and after the war than many more famous names of the period. As PUS from 1938 to 1946, he kept a tight grip on the whole range of foreign policy and was the closest adviser to three Foreign Secretaries: Halifax, Eden and Bevin. On top of that, he won Churchill’s trust for his mastery of detail and shrewd judgement. Like his military counterpart, Chief of the Imperial General Staff, General (later Field Marshal) Sir Alan Brooke, he attended most meetings of the War Cabinet. These were often convened late in the evening and dragged on interminably as Churchill clashed with his ministers or advisers or both. Brooke would go in all guns blazing when he thought Churchill was wrong on military strategy, making no effort to conceal his fury and sometimes snapping pencils in his hands as a result.

A draft of the 1941 Atlantic Charter with notes written in Churchill’s unmistakeable hand. (© Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office.)

Cadogan, although equally fearless in telling Churchill he was wrong on foreign policy when necessary, usually took a different tack – saying little, but making sure he was tasked with the followup. He would then labour deep into the night to come up with practical proposals to reconcile the differences around the Cabinet table. He had an uncanny ability to imitate Churchill’s distinctive writing style, which he put to good use, for example ghost-writing messages to Roosevelt or Stalin in his master’s voice. The next morning, he would take his work over to Churchill, who was often still in bed dictating to a secretary, cigar in hand, in the best of tempers, all the storm clouds of the previous night having cleared. The Prime Minister would sign off Cadogan’s drafts often with barely a glance. With one more problem solved, the PUS would return with a sigh to a new stack of papers on his desk.

Churchill rated Cadogan so highly that he took him to all the great wartime summits, while Eden stayed at home to mind the shop. The first of these took place in Placentia Bay off Newfoundland in August 1941. There Cadogan showed his true colours – this super-competent and unflappable civil servant was also a man with a powerful vision of the future peace and a gritty determination to see it through into a reality in the postwar years.

After two years of war, Britain stood alone in Europe and was on the defensive in the Mediterranean. Japan was becoming increasingly aggressive in the Pacific. Churchill was desperate to get some commitment from Roosevelt about the circumstances in which the US would come into the war. So the British team prepared carefully, while HMS Prince of Wales spent four days and five nights zig-zagging across the Atlantic to avoid the attentions of German U-boats. One of their objectives for the summit was to persuade the Americans to issue a pair of parallel UK and US Declarations, with the American one warning Japan that any further encroachment in the Pacific would put them on a collision course with the US. In this Churchill was to be disappointed – Roosevelt was only willing to give the Japanese a vague warning accompanied by a suggestion of further talks. But at their first meeting on 9 August, Roosevelt sprung a surprise. He proposed a different, joint, declaration on principles for the post-war world, and invited the British side to draft it.

Churchill jumped at the chance. Cadogan recalled in a memoir written in 1962:

Next morning (10 Aug), while I was having my breakfast on a writing table in the Admiral’s cabin, I heard a great commotion and a good deal of shouting. It turned out to be the PM storming round the deck and calling for me. He ran me to ground and said he wanted immediately drafts of the ‘parallel’ and the ‘joint’ declarations. He gave me, in broad outline, the sort of shape the latter should take. I hadn’t quite finished my eggs and bacon, but I pulled a sheet of notepaper out of the stationery rack before me and began to write.2

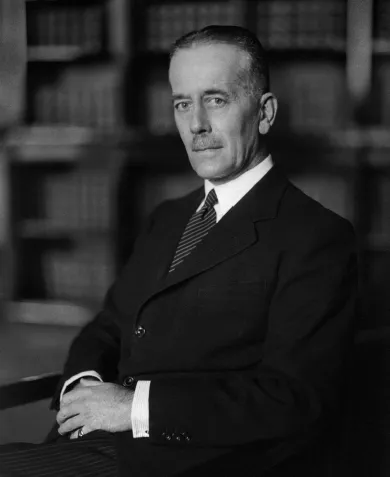

Permanent Under-Secretary for Foreign Affairs Sir Alexander Cadogan in his room at the Foreign Office in August 1941, the same month the Atlantic Charter was signed. (© National Portrait Gallery, London.)

Cadogan was the only expert on foreign affairs in Churchill’s delegation, on a warship 2,000 miles from home, and without the time or the communications to get any help from London. In his usual unruffled way, he got to work and produced a text. As he put it:

I had what I had written typed out and gave this first rough draft to the PM, who expressed general but not very enthusiastic approval. I think he made only one verbal change of no great importance. . .

Churchill passed on the text to Roosevelt. After several rounds of negotiation between Cadogan and his US opposite number, Sumner Welles, and then between Churchill and Roosevelt, the Atlantic Charter was agreed two days later (though the leaders never got round to signing it). The post-war order that would define the West for more than seventy years was initiated by this short document produced in such unpromising circumstances. It is all the more remarkable for being agreed between one country already in the thick of a fight for survival, and the other still a non-combatant nation with a strong isolationist lobby. It is worth looking at in a bit of detail because it laid the foundations for so many of the international structures which came to define the rest of the century.

Cadogan and Welles did not conjure up the Atlantic Charter from thin air. They wove together several strands of pre-war thinking. One source was President Woodrow Wilson’s fourteen-point plan presented to the Versailles Peace Conference in 1919. This envisaged a ‘general association of nations’ providing ‘mutual guarantees of political independence and territorial integrity to great and small states’3 which became the basis for the League of Nations. The Covenant of the League committed members to a compulsory system of dispute resolution, including economic and, if necessary, military sanctions against a violator. It was an ambitious effort to prevent future wars. But the US Senate refused to take on a commitment that could have drawn the US into disputes anywhere in the world. Weakened by the absence of the US, the dispute resolution mechanism of the League failed during the 1930s in the face of Italian aggression in Abyssinia, and the Japanese invasion of Manchuria.

The League of Nations became a byword for an organization which had high ideals, but which was too weak and ineffectual to impose them. Wilson’s idealism found another way forward when a group of US legal scholars persuaded French prime minister Aristide Briand in 1927 to propose a bilateral agreement with the US to outlaw war as an instrument of national policy. The US Secretary of State, Frank B. Kellogg, was at first reluctant, but agreed to pursue the idea in the form of a Treaty open to all nations. The Kellogg–Briand Pact (or the General Treaty for Renunciation of War as an Instrument of National Policy) was signed in 1928 by fifteen nations, including Germany and Japan. The parties agreed ‘to renounce [war] as an instrument of policy in their relations with one another’. The Treaty declared new international law, but provided no mechanism to enforce it. For that reason it was readily adopted by the US Senate.4

The outlawing of war was one of the pre-war ideas that fed into the Atlantic Charter. Another was the importance of government action to promote the economic and social rights of individuals. This was very much a Roosevelt theme: it was part of the inspiration behind his New Deal programme in the 1930s in response to the Great Depression. Roosevelt repackaged this way of thinking as ‘Four Freedoms’ in his message to Congress in January 1941.5 He took the opportunity to give his list a sweeping international reach:

The first is freedom of speech and expression – everywhere in the world.

The second is freedom of every person to worship God in his own way – everywhere in the world.

The third is freedom from want – which, translated into world terms, means economic understandings which will secure to every nation everywhere a healthy peacetime life for its inhabitants – everywhere in the world.

The fourth is freedom from fear – which, translated into international terms, means a worldwide reduction of armaments to such a point and in such a thorough fashion that no nation will be in a position to commit an act of physical aggression against any neighbor – anywhere in the world.

One Roosevelt adviser summarized the New Deal approach as ‘the duty of government to use the combined resources of the nation to prevent distress and to promote the general welfare of all the people’.6 Similar thinking was under way in the British government leading up to the Beveridge Report in 1942, which proposed a social security system and laid the foundations for the post-war welfare state and the NHS. The Atlantic Charter was, in some ways, the New Deal applied to international affairs.

The idea of a joint Anglo-American declaration of aims for the post-war world had been doing the rounds well before the meeting in Placentia Bay. Thinking in the State Department concentrated more on the economic than the geopolitical issues. One of the ambitions of the Secretary of State, Cordell Hull, and his Deputy, Sumner Welles, was to tie the British down to support for the principle of free trade, and therefore to abandon the system of ‘imperial preference’ which kept Britain’s trade with its Empire shielded from wider competition. They also wanted to make sure the British would not enter into any secret treaties with other countries about frontier adjustments after the war, remembering how much these had complicated the settlement after the First World War.

When Cadogan sat down over his bacon and eggs to write out a first shot at this manifesto for the post-war world, he had this hinterland very much in mind – not least because he had spent several hours the previous day skirmishing with Welles on secret treaties and open trade. He was also Britain’s foremost expert on the League of Nations, having been the UK’s representative for a decade after 1923. Since the overriding British priority was to get the Americans as firmly committed as possible to the war effort and the international security arrangements that would be needed for an Allied victory, Cadogan took care that his draft gave great prominence to themes that would appeal to Roosevelt.

Cadogan organized his text into five principles. The first three survived virtually unchanged into the final version. The first and second principles followed the language of the League of Nations Covenant in committing both countries to ‘seek no aggrandisement, territorial or other’ and to oppose ‘territorial changes that do not accord with the freely expressed wishes of the peoples concerned’. The third undertook that Britain and the US would ‘respect the right of all peoples to choose the form of government under which they will live: they are only concerned to defend the rights of freedom of Speech and Thought without which such choice must be illusory.’ The first phrase was Cadogan’s way of reassuring the Americans that there were to be no secret treaties about frontiers in Europe. He and Churchill seem not to have anticipated the inevitable consequence that it was duly seized upon in India and across the Empire by all those campaigning for independence.7 When he came to produce a revised draft, Welles changed the second phrase – he thought it would sound to US Congressional ears too much like an American commitment to enter the war. In his revised version, the third principle read less like a call to arms:

Third, they respect the right of all peoples to choose the form of government under which they will live: and they wish to see sovereign rights and self-government restored to those who have been forcibly deprived of them.

Cadogan’s fourth and fifth principles were the ones which proved most contentious. The fourth covered the vexed issue of free trade – or rather, in Cadogan’s draft this was evaded. He proposed a phrase so general as to be meaningless. The two countries would ‘strive to bring about a fair and equitable distribution of essential produce’. Having discussed the British draft with Roosevelt, Welles made this point much blunter:

Fourth, they will endeavour to further the enjoyment by all peoples of access without discrimination and on equal terms to the markets and to the raw materials of the world which are needed for their economic prosperity.

That in turn ran into the brick wall of Churchill’s commitment to imperial preference. He told Roosevelt over dinner on 10 August that he was determined to preserve Britain’s pre-war preferential arrangements: ‘the trade that has made England great shall continue, and under conditions prescribed by England’s Ministers. . . There can be no tampering with the Empire’s economic arrangements.’8 When Churchill and Roosevelt discussed the American counter-draft on the morning of 11 August, Churchill avoided locking horns with Roosevelt on substance, and chose instead to play the timing card, asserting that it would be very difficult to get quick agreement from the dominions for a far-reaching change of this kind to the existing trade arrangements. He was well aware that Roosevelt was impatient to get the meeting finished and announce the results. Churchill’s solution was a classic bureaucratic manoeuvre: to insert a get-out clause into the American text in the form of a qualifier ‘with due regard for our present obligations’. To Sumner Welles’s great disappointment, Roosevelt caved in and accepted.

The fifth principle in the final version of the declaration was an addition proposed by the British Cabinet. Churchill asked Clement Attlee in London as Acting Prime Minister to convene the Cabinet in the middle of the night, between the two main rounds of negotiation in Placentia Bay, to approve the draft he telegraphed to them. Attlee called the members of the Cabinet together at 2 a.m. – a remarkable feat, even in wartime. They made two suggestions, one on the trade article, which Churchill did not press, and another to insert a new article on social security:

Fifth, they desire to bring about the fullest collaboration between all nations in the economic field with the object of securing for all improved labour standards, economic advancement and social security.

This boosting of the ...