![]()

CHAPTER 1

Scepticism – From the Maelstrom of Knowledge into the Labyrinth of Doubt

Doubt is not a pleasant condition, but certainty is absurd.

Voltaire

Iwould love to be certain, to be sure of something, but my anxiety makes that unlikely. Perhaps my perpetual nervous doubt has had some advantages for me, as it has meant that whilst science has encouraged a deepening of my scepticism about the world, I have not had to painfully sever myself from any strongly held, dogmatic beliefs.

In his book Science and Hypothesis the French mathematician and physicist Henri Poincaré wrote, ‘To doubt everything and to believe everything are two equally convenient solutions; each saves us from thinking.’ Finding the Goldilocks portion of doubt – the doubt that is ‘just right’ – can be tricky. The author Robert Anton Wilson, who co-wrote The Illuminatus Trilogy, a wonderfully playful and adventurous romp through all the conspiracies there have ever been, encouraged universal agnosticism. This was not merely agnosticism about the gods; this was agnosticism for all your beliefs.

Good science is never certain. Though it might be sure it is providing the best answer for the time being, you always need to be prepared to loosen your grip. This is not only true of science, it should be true of all beliefs, but it is not easy. We are tribal and we like to feel that we belong. To belong often meets to be united by your beliefs and, even more so, united by hatred of those who contradict those beliefs.

We are all victims of our cognitive dissonance. Our desire to hold on to beliefs about the world means that people often follow all manner of circuitous routes of thought in order to preserve their beliefs, even when they become increasingly preposterous. With the dominance of social media, there is now a perpetually pumping plumbing system that sprays out opinions twenty-four hours a day. We are never more than two seconds away from an utterly bizarre opinion that is rabidly held.

Sitting in rooms with physicists, I sometimes observe their perplexed faces as they try to understand the erratic and destructive beliefs and decision-making of other humans. ‘Haven’t they seen the statistics and the graphs?’ they wonder. For some, this is why they were drawn to physics. Even in a probabilistic universe, the paths of electrons are easier to predict than the actions of other human beings. Evidence can often play a very minor part in why we believe what we believe, so when the physicist tries to refute your ideology with years of carefully accumulated evidence, you can shrug it off and return to your invisible leprechaun farm.

I can also find myself frustrated by scientists. It seems to me there are some who consider that they have such control over their own minds that the pure evidence they have discovered means they would never fall victim to any cognitive dissonance. I have also grown to dislike those sneering T-shirt slogans or memes that say, ‘Science doesn’t care about your opinions’, as if by being a scientist, their feelings and biases are always usurped by their superior brains, which can manage to neatly box their emotions, only occasionally releasing them for birthdays, funerals and screenings of The Shawshank Redemption.

It goes both ways. When scientists are particularly attached to an idea, evidence may not be enough; and again, though they might deny this, emotion may play its part.

Fred Hoyle was a brilliant scientist. With US physicist Willy Fowler, he demonstrated that all the elements of our world originated from inside stars and were then projected through the universe via stellar explosions. The romance of us being made from star-stuff was confirmed by his work. It provided us with a beautiful story, offering us another sense of connection with the whole universe. Pondering on the journey that the atoms that make up you and me have made throughout history is meditation time well spent. Fred Hoyle is probably best known, though, as the astronomer who, despite increasing evidence, would not accept the Big Bang theory. He continued to prefer his steady-state theory. Astrophysicist Chris Lintott thinks that what lay at the heart of Fred Hoyle’s thinking wasn’t a scientific dispute; it was his hope and desire that the universe would go on for ever. After all, when the universe ends, physics ends, too. ‘Hoyle realized very early that if you have a universe that’s changing, that implies not just that there’s a beginning but that there’s an end, even if it expands for ever. And so his steady-state theory was a way of getting away with that, because you’re continually producing new raw material from which you can keep making stars and planets and astronomers,’ Chris explains. When considering scepticism, it is important to realize that the clear thinking of scientists may also be polluted with emotional attachment and egotism.

With curiosity, though, comes doubt; and if your doubt remains active, you may become marked as a sceptic – something often confused with being a cynic. The sceptic, like the atheist, can be seen as a killjoy. There you are, having all the fun of believing that the Earth is flat, or shunning a potentially lifesaving vaccine because a Hollywood celebrity made a five-minute YouTube film that was informed by someone else’s five-minute YouTube film, which was in turn informed by a YouTube film by a vitamin-pill salesman (and the infinite regress of misinformation goes on), and some sceptic comes along and suggests that it might all be a bit more complicated than that. The importance of doubt working in tandem with science is potentially life-saving. Some may say at this point, ‘But isn’t rejecting the Earth being a sphere, and rejecting vaccines, scepticism?’ And I would suggest that you try arguing with the people who hold these opinions. Their beliefs require a rejection of a great deal of evidence, often based on suspicion or paranoia and the unproven ideas of secret cabals, not really offering testable alternative realities or ideas.

There is a reason why fundamentalist religious and political systems often ban books. It’s because they can be full of ideas and possibilities that can reframe the world in a way counter to that set out by those systems. Books are pliers for the barbed wire with which a dictator wishes to encircle someone’s mind. Once, in Canberra, I spoke to a man who had been brought up in a fundamentalist Christian commune. While other teenagers in Australia may have been hiding creased pornography under their mattress, he had a book of essays by the philosopher A. C. Grayling. This was the key to his rebellion.

A book brought me to sceptical thinking, too, though I did not have to hide it under the mattress, which was fortunate, as I was sleeping on a futon with a very thin mattress and the sharpness of a book corner could have caused spinal damage. In Sceptical Essays, Bertrand Russell wrote that scepticism will diminish the incomes of clairvoyants, bookmakers and bishops. He tells the story of Pyrrho, the first Greek sceptic philosopher, who considered that ‘we never know enough to be sure that one course of action is wiser than another’. When Pyrrho saw his philosophy teacher with his head stuck in a ditch, he didn’t pull him out, as he didn’t think he had enough information to be certain that his teacher didn’t want to have his head stuck in a ditch. After others pulled the teacher’s head out, his teacher congratulated Pyrrho for correctly interpreting his philosophy, even if it did lead to him having his head stuck in a ditch for longer than it needed to be. (We are never told how he got his head stuck in a ditch in the first place, and I am not sure I would hold someone’s teachings in such high regard if they were the sort of person who found themselves in such a position. I am also not sure he would have congratulated Pyrrho quite so heartily if no one else had pulled his head out of the ditch. By the third day, say, even the most stoical of stoics could have become fed up of having his head stuck in a ditch, especially if goats were beginning to sniff around.)

‘They swim. The mark of Satan is upon them. They must hang’

My interest in scepticism grew before my interest in science was rekindled. It really took hold at the witch trials, or at least the site of witch trials, both historical and fictional.

It was the story of the small English town of Lavenham that sparked it all off for me. Its connection to witch trials made it a good place to start questioning why we believe what we believe. Here was one of the locations where the vagaries of nature – whether crop failure or erectile dysfunction – had led to women being burnt at the stake if they failed to do the proper thing and demonstrate their propriety by drowning in a river.* ** Women from Lavenham were tried as witches, but the most famous Lavenham witch trials were fictional, in the film-cult classic Witchfinder General, the final film of the far-too-short life and career of enfant terrible film director Michael Reeves,* with Vincent Price playing Matthew Hopkins in the title role.

After wandering around the Lavenham square where Price’s Hopkins set fire to Maggie Kimberly, I went into an antique shop, looking for a Toby jug of interest or a framed cigarette card of Boris Karloff. Instead I found a second-hand copy of James Randi’s Psychic Investigator, the book of the TV series in which the conjuror and escapologist tests the claims of spiritualists, dowsers, telepaths and suchlike.

My first attraction to these stories was as low-hanging fruit for stand-up comedy routines. I was particularly keen on the toe-curling tales of floundering psychic mediums struggling for any sort of ghost that might connect with their audience. My favourite was the medium who stood onstage and announced that the ghost who had sat down beside him liked cheese-andpickle sandwiches – one of Britain’s most popular sandwiches, especially among the generation that were most likely to have died recently, and likely to be popular with his living audience too. Somehow, in a room of more than 500 people, none had a deceased relative who was remembered for being fond of this highly popular sandwich – surely a statistical aberration. Labouring over the details of the snack, as if the audience might have forgotten what a sandwich was, the increasingly flustered and irritated psychic still found no takers. Finally a sheepish man at the back recalled that his father loved cheese, but that he was not allowed to eat it. This was the spirit connection that the medium now said he was looking for. Due to poor communication between the living and the dead, ‘lactose-intolerant’ was translated as ‘cheese and pickle’.

Though I enjoyed the laughter that I could generate from such stories, they made me angry, too. The dairy-product-confused psychic could make as many cock-ups as he liked and still play bigger rooms than me. Each preposterous failure would be forgiven; every minor hit was a miraculous success. Fortunately, with even more bizarre and clearly preposterous theories making it into the twenty-first-century mainstream, I barely have time to be utterly appalled by such ghost-whisperers.

Some of James Randi’s most damning investigations involved faith healers, a similar scam to psychic mediums, although with the ill being preyed upon, rather than the bereaved being mocked. One of his most famous cases from the late 1970s concerned Peter Popoff, a minister who was stunningly accurate in his healing powers. God would tell him the full names and addresses of the sickly people in his audience, and exactly what was wrong with them. He would then heal them with his touch and watch the donations flood in. Once scrutinized by Randi, it became apparent that this connection to God was via an earpiece that broadcast his wife’s specific instructions, based on information that the audience had volunteered on entry. His gift from God was actually a purchase from a high-end electrical shop. The scam was revealed on Johnny Carson’s The Tonight Show, one of the USA’s biggest TV shows. The revelations destroyed the Popoff ministry and he never worked again… … is what I wish I could write. Sadly, years later the Popoff ministries continue to be active, now under his slogan ‘Dream Bigger’. Popoff certainly doesn’t want an audience that is too awake – the more docile and close to a dream state, the better. On his donation page he reminds you to donate big, because that is what 2 Corinthians 9:6 tells you to do.1 God has monetized his miracles. On Popoff’s Miracle Spring Water page, you are reminded: ‘DO NOT INGEST THE MIRACLE SPRING WATER’. Overly powerful miracles can prove toxic and cause diarrhoea.

When I interviewed Randi about the Popoff investigation forty years on, it was clear that he was still disgusted and disturbed that Popoff could abuse and manipulate people. His voice cracked when he recalled some of the abusive, dismissive and derogatory language that was used to describe the people to whom Popoff’s wife was leading him. Not only were they fleecing these people, they were laughing at them as they did so.

Some people may defend faith healing, suggesting that it could have some place in people’s physical well-being. If someone is persuaded that their pain can be alleviated through the love of Jesus, it might act as a placebo; but when it comes to cancer, HIV or numerous other diseases, positive thinking alone will not work.

The grand plan is an evil plan, but at least it’s a plan

It’s good to be a sceptic, in my view, but one criticism of sceptics is that they come across as a bunch of know-it-alls, and that having several sceptics together can lead to sneering and blanket dismissals of other people’s more dubious but precious beliefs. I would love to look back on my past exploits and say that I never got an easy laugh on stage via casual dismissiveness and a hearty lip curl (I was the Elvis of the sceptic movement in my youth). But sometimes, the shortest cut to the quickest punchline left ethics at the kerb. Atheists, sceptics and people who have recently discovered that they like modern jazz can all be overly zealous. The trick is to avoid getting a tattoo too soon, as the Thelonious Monk and John Coltrane motifs on my shoulder blades sadly attest to (and I will say no more about the Christopher Hitchens and Richard Dawkins tattoos on my knees).

Sceptical paranormal investigator Hayley Stevens has written about distancing herself from the sceptic movement. She is increasingly driven by an approach ‘that doesn’t compromise on science, but also doesn’t compromise on respect and compassion, either’.2 It is this reasoned and compassionate approach that seems to underline much of the work of The Merseyside Skeptics. They are the sort of sceptic group that all sceptic groups should aspire to. Obviously that is only an opinion, based on the evidence that I have seen of them so far, which might change as other things come to light. Their reason for being seems to come from a genuine concern for other humans. It is not simply about disproving a theory or belief; it is about working out why people are attracted to thinking that could be damaging to them or others, or where such thinking is just plain wrong.

Revealing that an individual is a charlatan who uses the methods of a con artist to hoodwink their audience only deals with the surface problem; for them, the more important role is to work out how to alert people to the fact that they are being conned, and make the wider world know that it does matter.

The Merseyside Skeptics’ co-founder, Michael Marshall, spends a lot of time mixing with flat-Earthers, Moon hoaxers and conspiracy theorists at their numerous conventions. He presents a long-running podcast whose manifesto is to ‘examine beliefs from outside of the mainstream, exploring how those beliefs are constructed and what evidence people believe they have to support their case. We believe in approaching subjects with respect and an open mind, engaging with people with different viewpoints in an environment that is polite and good-natured, yet robust and intellectually rigorous.’

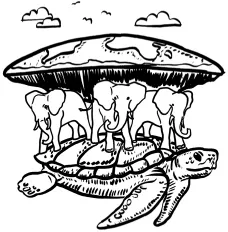

Michael wants to understand what has brought people to positions where they consider reason and evidence to be propaganda. It can be a very paranoid landscape that he inhabits. Once you have accepted a flat Earth, then the Apollo missions are all lies; and once you have rejected the curvature of the Earth and the Moon landing, you can move on to refuting gravity, the shape of the stars, the structure of the universe – in fact, you can refute anything you want, ranging from vaccines to the existence of The Beatles (Paul McCartney didn’t die in 1966, he never existed in the first place. This is the basis of the holographic Mersey Beat conspiracy). All information counter to your position is the product of the Illuminati, an untouchable group who have a bloodline going back centuries, and who are tied to the Knights Templar and to the British royal family. From that point onwards, the world can be whatever dystopian nightmare you want it to be.

Michael talks me through a lecture he saw at a flat-Earth conference, typical of its kind. The speaker simply voiced everything that was in his head – a dirt...