![]()

1

JOACHIM’S CHILDREN

Tiger got to hunt,

Bird got to fly;

Man got to sit and wonder, “Why, why, why?”

Tiger got to sleep,

Bird got to land;

Man got to tell himself he understand.

—Kurt Vonnegut1

In the late twelfth century, the kings and queens of Europe undertook the arduous journey to a monastery in the remote Calabrian hills to bask in the legendary wisdom of a nearly forgotten Cistercian abbot named Joachim of Fiore. Passing through on his way to the Third Crusade in 1190–1191, Richard the Lionheart sought his vision of the future.2

The quiet intellectual abbot was fond of numbers and historical analogies, and what attracted Europe’s rulers to his monastery was his organization of human history into three ages that foretold a coming golden era. Joachim, unfortunately, had unwittingly lit a prophetic fuse. His vision of the future spoke eloquently to the downtrodden poor and stirred revolution in their hearts, and over the following centuries, his initially peaceful schema would mutate into a bloody end-times theology that engulfed wide swaths of Europe.

Understanding how this happened invokes the Bible’s three major end-times narratives: the Old Testament books of Ezekiel and Daniel, and the New Testament’s last book, Revelation. While these three books may seem obscure to modern secular readers, they help to explain the cultural polarization between Christian evangelicals and the rest of American society that has become so evident the past several election cycles. For the former, the contents of these three books are as familiar as the stories of the American Revolution and Civil War; for the latter, they are largely terra incognita. Further, even evangelicals are often unaware of the ancient Near East history behind these narratives, particularly the complex interplay among the Egyptians, Philistines, Assyrians, Babylonians, Persians, and the two Jewish kingdoms, Israel and Judah.

Ezekiel, Daniel, and Revelation provide the backdrop to a series of end-times religious mass delusions that were in many ways similar to the tragedy at Cheiry. Such manias have been a nearly constant feature of the Abrahamic religions since their births, most prominently involving the town of Münster in the sixteenth century, the Millerite phenomenon in the mid-nineteenth century United States, and the repetitious and widespread predictions of imminent end-times that followed the establishment of the modern state of Israel.

Religious manias tend to play out in the worst of times, during which mankind desires delivery from its troubles and a return to the Good Old Days, a mythical bygone era of peace, harmony, and prosperity. One of the earliest surviving Greek poems, Hesiod’s “Works and Days,” from around 700 b.c., expresses this well. Greece at that time was desperately poor, and the author scratched out a hard living on a farm in Boeotia, just northwest of Athens, which he described as “bad in winter, sultry in summer, and good at no time.”3 Things, Hesiod imagined, must have been better in years past. First came the gods on Olympus, who made a “golden race of mortal men” who

lived like gods without sorrow of heart, remote and free from toil and grief: miserable age rested not on them; but with legs and arms never failing they made merry with feasting beyond the reach of all evils. When they died, it was as though they were overcome with sleep, and they had all good things; for the fruitful earth unforced bare them fruit abundantly and without stint. They dwelt in ease and peace upon their lands with many good things, rich in flocks and loved by the blessed gods.4

The next generation was “made of silver and less noble by far.” They were still blessed, but had sinned and failed to offer sacrifices to the gods, and were followed by a third generation of men whose armor, houses, and tools were of bronze. The gods, for some reason, gave the fourth generation a better draw than the third; half died in battle, but the other half lived as demigods. The fifth generation, Hesiod’s, was “a race of iron, and men never rest from labor and sorrow by day, and from perishing by night; and the gods shall lay sore trouble upon them.” Their children, Hesiod predicted, would fall even further short—venal, foulmouthed, and, worst of all, disinclined to support their parents in their dotage.5 Hesiod had stolen a more than two millennia march on Thomas Hobbes’s Leviathan: life was indeed solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.

The misery of Hesiod’s day, bleak as it was, was at least intrinsic to the local land and culture—the poverty of the soil, the venality of man, and the aggression of neighboring city-states. A Greek city’s hostile neighbors, after all, shared the same religion and culture, and while they often enslaved their defeated neighbors, before the Peloponnesian War they generally did not put them to the sword.

Around the same time as Hesiod, several hundred miles away, the Hebrews’ troubles were of a more existential sort, and they gave rise, eventually, to the most common current-day end-times narratives, which promised a happier human existence in the next world, at least for those who kept the faith and survived the transition.

How the Jews came to settle the Holy Land remains a mystery, as historians question both the existence of Moses and the Exodus from Egypt. What is beyond dispute is that the Israelites had an easier time subjugating the Canaanites, Palestine’s culturally more advanced but less aggressive original inhabitants, than they had with the ferocious “Sea Peoples” who followed. The latter, a mysterious race, plagued Egypt and possibly extinguished several western Mediterranean civilizations, including the Mycenaean. Not long after the supposed Exodus, a local branch of the Sea Peoples, the Philistines, established a beachhead in the area between the modern Gaza Strip and Tel Aviv and began to push inland.

The Philistine threat served to unite the small and disparate Israelite tribes. They eventually settled on Saul, a sometime mercenary of the Philistines, as their leader. He defeated his former employers and so brought about the beginnings of unity among the Hebrews. Upon his death not long after 1000 b.c., one of his lieutenants, David, who had also served the Philistines, succeeded him. A more militarily talented and charismatic leader, he brought under his dominion not only the northern and southern states, Israel and Judah, respectively, but also conquered as his own personal possession a heavily fortified town, Jerusalem, held by the Canaanites.

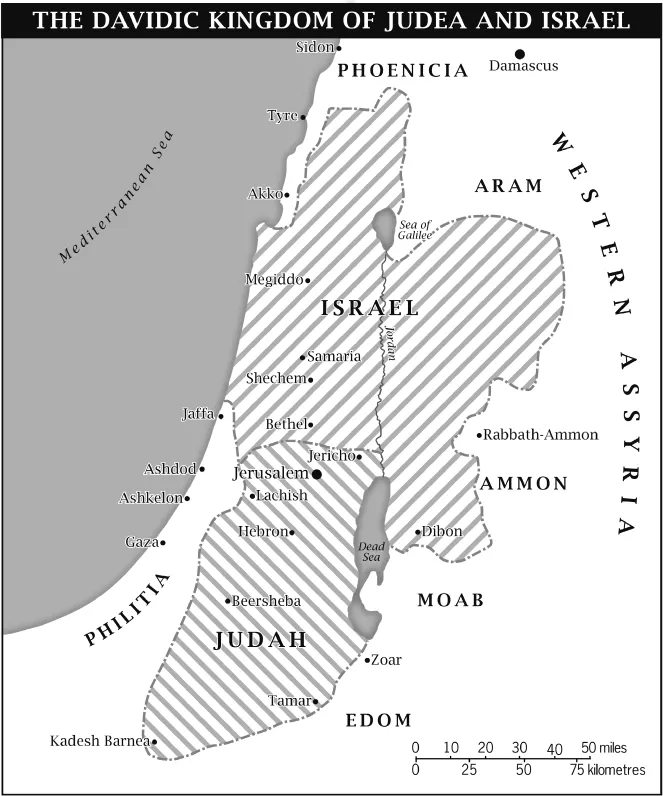

Under David, the Jewish domain reached its maximum geographical extent, reaching as far north as Damascus. What is today called the “Davidic Kingdom” was not a unified state, but rather consisted of three separate components: Judah and Israel, whose individual kingships David separately occupied, and Jerusalem, his personal property.

His son Solomon held this confederation together. An ambitious builder, he erected a series of palaces, forts, and places of worship, most notably Jerusalem’s First Temple. He also enthusiastically practiced marital diplomacy; he betrothed a pharaoh’s daughter and maintained, at least according to I Kings, seven hundred other wives and three hundred concubines. One of his forts, at Megiddo, would later become better known by its Greek name: Armageddon.

Solomon’s edifice complex, and particularly the huge labor corvées necessary for his building schemes, bred resentment, and when he died in 931 b.c., his son Rehoboam refused to travel north to Israel’s capital, Shechem, for his coronation, and so Israel left the confederation.6

The north-south schism proved fatal to Jewish independence when the Assyrians became the region’s preeminent military machine. By the ninth century b.c., the northern state, Israel, was paying them tribute, and when Tiglath-Pileser III gained the Assyrian crown in 745 b.c., he hurled his conquering legions westward and carved Israel up. His successors, Shalmaneser V and Sargon II, completed the conquest by 721 b.c., and, as recorded in Sargon’s Annals, “27,290 men who dwelt in it I carried off, fifty chariots for my royal army from among them I selected. . . . That city I restored and more than before I made it great; men of the lands, conquered by my hands, in it I made to dwell.”7

Sargon deported the northern elites to the banks of the Tigris and Euphrates; they disappeared into history’s mists as the ten “lost tribes,” most likely assimilated into the local Mesopotamian population. The Assyrians then turned their sights on the southern state, Judah, and mounted an abortive assault in 701 b.c., and then unaccountably left it alone for a century thereafter, possibly as a buffer state between them and the Egyptians. This hiatus saved Judah, and the Jewish people, from the oblivion suffered by its northern branch.

When the Assyrians fell to the Babylonians around 605 b.c., the Jews faced an even more fearsome conquering force in the person of their king, Nebuchadnezzar, who in 597 b.c. conquered Jerusalem and, according to II Kings,

. . . Jehoiachin the king of Judah went out to the king of Babylon, he, and his mother, and his servants, and his princes, and his officers: and the king of Babylon took him in the eighth year of his reign.

And he carried out thence all the treasures of the house of the LORD, and the treasures of the king’s house, and cut in pieces all the vessels of gold which Solomon king of Israel had made in the temple of the LORD, as the LORD had said.

And he carried away all Jerusalem, and all the princes, and all the mighty men of valour, even ten thousand captives, and all the craftsmen and smiths: none remained, save the poorest sort of the people of the land.8

Worse was to come. Around 587 b.c., Zedekiah, the puppet installed by the Babylonians, rebelled. In response, the Babylonians breached Jerusalem’s wall and poured through it. The king fled but was caught near Jericho, where the Babylonians “slew the sons of Zedekiah before his eyes, and put out the eyes of Zedekiah, and bound him with fetters of brass, and carried him to Babylon.”9

The Judeans must have known, given the experience of their vanished northern neighbors, that Nebuchadnezzar threatened their culture and very existence with extinction, and so they sought a drastic solution that their Greek near-contemporary, Hesiod, whose culture was not existentially threatened, did not seek: a miraculous cataclysm that would deliver them from oblivion.

Among the exiles carried off to the banks of the Euphrates along with Jehoiachin in 597 b.c. was a Temple-trained priest named Ezekiel. His book, written either by him or by others in his name, opens five years later, around 592 b.c., with his vision of the heavens opening to reveal a chariot carrying the Lord drawn by four phantasmagorical winged creatures, each with four faces: human, lion, ox, and eagle.

Whoever wrote this first major apocalyptic book of the Bible did so over the decades during which conditions in the Holy Land deteriorated. As described in II Kings, the Babylonians had exiled Judah’s royalty, priests, and wealthy, but left behind a large underclass. Initially, the elites sent to Babylon were optimistic about their prospects for a quick return, but the destruction of Jerusalem and the First Temple in 587 b.c. drove their evolving narrative in an apocalyptic direction.

Ezekiel’s author turned his story away from the impieties of Judah that had brought about its...