![]()

CHAPTER 1

The Power of Exponential Growth

If a man is proud of his wealth, he should not be praised until it is known how he employs it.

Socrates

If you ask fifty people what money is, you’ll get fifty different answers: it’s a peculiarly hard thing to define, so let’s start by trying to pin that down. That definition will underpin the most basic ways you can make your money grow and help to explain why exponential growth is the key to successful wealth accumulation.

What is Money?

At its most basic, money is just a mathematical tool for counting and measuring value. In pre-monetary societies goods could be traded by barter in which, for instance, a sack of grain might have been swapped directly for pots or beans or for a day’s labour in the fields.

Let’s imagine a transaction where one dairy cow was swapped for three bushels of wheat. We could use a visual equation to express their comparative value (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. This represents the algebraic equation c = 3b (where c represents one cow and b represents one bushel).

But you can only use pure barter if you have exactly the goods the other party wants and vice versa. Otherwise, you can end up in complicated webs of buyers and sellers where person A gives person B a cow, they give their wheat to person C, person C gives person D some beehives, and they give person A their pots and pans. This would be monstrously tricky to choreograph. So, very quickly systems of money and credit were developed. By using tally sticks or other primitive records of trades, people could sell their goods or services and store a credit to be used for purchases at a later time. If we call the unit of currency ‘x’, then we might have market prices of 15x for a cow and 5x for a bushel (see Figures 2 and *).

Figure 2. One cow costs 15x.

Figure 3. One bushel costs 5x.

In algebra, we would represent these as:

c = 15x

b = 5x

We can also manipulate these equations to get valuations for one unit of x:

Note that money can be treated as an additional item in the marketplace, whose own value can be measured in terms of other items. Its main advantage is that you can use it as an intermediary that enables transactions involving other items.

So we immediately have counting as the basis of monetary systems. (In fact, the whole act of counting large numbers may have been inspired by commerce – there is evidence that primitive societies would count ‘one, two, three, many …’ or only up to ten or twenty, based on fingers and toes.) And we also have money being used from the start as a measure of comparative value.

From an early point, debt was also part of monetary systems – many societies had rules against usury (charging interest on lent money) but any system that recognizes a credit owed by one person to another already contains the concept of debt. In fact the concept of negative numbers was initially introduced by Chinese mathematicians specifically to deal with the problem of keeping accounts which recognized both credits and debits – in a ledger, the red debits were subtracted while the black credits were added.

Some people distinguish ‘real money’ from ‘token money’ or ‘fiat money’. By real money they mean objects such as gold, which they see as having a real, intrinsic value, as opposed to tokens such as wooden coins or cowrie shells (which were being used as money tokens three millennia ago on the shores of the Indian Ocean). I would argue that money is always to some degree a token or representation, regardless of its physical form, but I don’t want to get into the complex debate over whether gold money is more real than, say, the US dollar other than to say this: any kind of money, whether it be gold or paper, government-backed or private, digital or a plastic token, can be valued only in relative terms.

What this means is that the value of a unit of money can only ever be measured in terms of the goods and services (or even other currencies) it can be exchanged for.

So there is no such thing as inherent or absolute value: you can measure the current value of gold against wheat, a dollar against gold, or even the value of one yen against the value of one euro. But it is meaningless to describe any of these goods as having value in themselves without referring to who is valuing them and what they might exchange for them. All monetary values are relative and all of them fluctuate over time. And if, for instance, the price of petrol in dollars increases, it is equally valid to say that the price of dollars, as measured in petrol, has fallen.

As well as being relative, monetary value is always subjective. The same bottle of water might be worth nothing to someone who lives by a clean stream, but worth a million dollars to you if you are lost in the middle of a desert and at death’s door.

The art of wealth management is based on identifying differential value and fluctuations in value. This concept is perhaps most easily understood when you consider the idea of ‘net worth’. This is defined as the amount of money you would end up with if you sold all your assets and paid off all your debts at current values.

It can be hard to shake the idea that money does or should have an objective value. But in these days of quantitative easing (and money printing) it should be clearer than ever that money itself can gain or lose value. And it gives us a much more rigorous mathematical basis for thinking about money if we regard it simply as an item that can be exchanged for other goods and services.

Remember that money is only a relative measure of exchange value, a way of counting the goods, services and assets it can be swapped for. At any given moment we can define the comparative value we would ascribe to two items a and b using the equation a = nb. And remember that the value of money fluctuates as well as the value of those goods and services. So value is relative, subjective and fluctuating. The main ways we can increase our wealth over time are by taking advantage of variations in value (for instance, by selling something for more than it cost us) or by adding value (for instance, creating wealth by making something more valuable out of raw materials).

Buy Low, Sell High

The next basic thing to bear in mind is that economic transactions generally rely on two individuals or groups placing a different value on the same item and then agreeing a mutually acceptable price. (If the two parties value the item exactly the same, they may agree a deal, but neither will have a strong motivation to do so.) Suppose you go out tomorrow planning to buy a second-hand car, let’s say you are willing to pay up to £3,000, while the seller is willing to sell for at least £2,500. In this case a deal can usually be done somewhere in between the two prices, and this will help to set the market price, which is the theoretical average of many similar transactions.

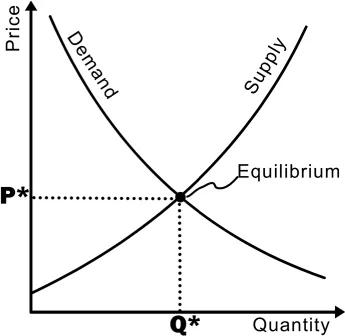

The supply and demand curves (see Figure 4) that are used in economic theory are just easy ways to show how prices are set in markets. You can use mathematical tools to describe idealized versions of markets, and these are valuable analytical tools so long as you remember that the idealized markets they describe aren’t actually real.

Figure 4. A supply and demand chart: As the price rises, supply tends to rise, meaning more people are willing to produce or sell an item, while demand tends to fall, meaning that fewer people are willing to buy the item. Theoretically the market price, or equilibrium price, will be found where the demand and supply curves meet.

Similarly if you buy a share, then this transaction works because you are assuming that the share is undervalued or valued correctly while the seller is assuming it is overvalued or valued correctly.* There may be rational or irrational reasons for these assumptions, but the key point is that the buyer and seller have different motivations and reasons for valuing these items differently and a compromise is reached. So rather than talk about ‘value’ it is often more useful to look at the market price, which can be measured.

If you want to make money, you have to think about the ways in which you can exchange assets, goods or services of varying price in a way that allows you to accumulate more money or possessions.

There are fundamentally four ways you might approach this task.

The first is to sell your labour for a wage or salary. In other words, get on your bicycle and go out and find some work.

The second is to create a business, large or small, in which you create goods or services. In this process you take the raw materials (whether they be labour, ingredients, materials or ideas) and create something that can be sold at a higher price. For instance, you might buy modelling clay and make brooches that you can sell for a higher price, and advertise them online via social media to keep your costs down. By adding value to the raw materials, you are creating wealth.

The third is to invest in other people’s businesses and wealth creation, either directly (by investing in the business of a friend, for instance or via stocks and shares, which you can buy directly or via a broker).

The fourth is to take advantage of the variation in value of assets, buying at low points and selling at high points – this is the basic activity of any trader who sells goods for a higher price than they pay for them, but it also describes the activities of speculators and gamblers. (It can be hard to pin down the distinction between speculation and investment, but it’s worth thinking about whether the money invested is genuinely helping others to create wealth. If not, it’s probably speculation rather than investment.)

However you aim to make your money, the obvious mathematical rule of ‘buy low, sell high’ is applicable in a world of fluctuating values. Even in the world of work, you can analyse the time a...