![]()

ONE

AMERICA’S IMPERIAL INHERITANCE

I never knew a man who had better motives for all the trouble he caused.

Graham Greene (1904–91), The Quiet American1

There will be times when we must again play the role of the world’s reluctant sheriff. This will not change – nor should it.

Barack Obama, Audacity of Hope (2006)2

If we’re going to continue to be the policeman of the world, we ought to be paid for it.

Donald Trump, Crippled America (2015)3

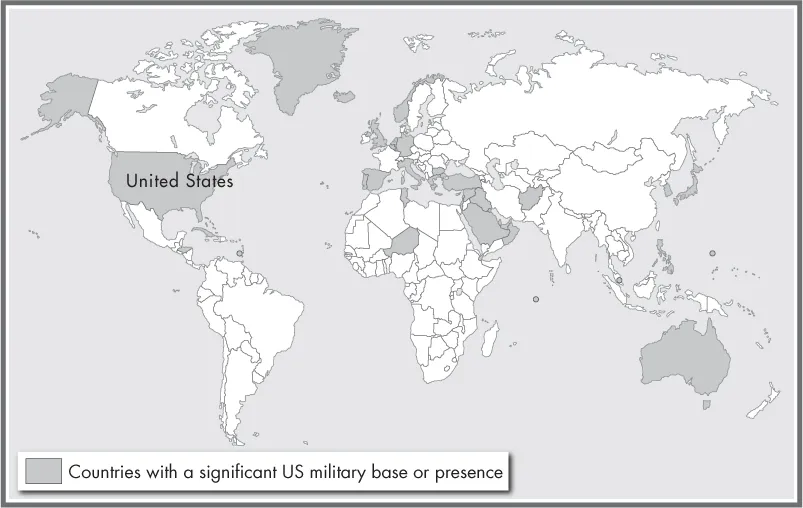

Map 1 The global military presence of the United States, 2019 (circles indicate countries or territories with a US base that would be too small to appear otherwise)

Opinions around the world differ sharply over whether the USA should conduct itself like a global empire, and whether doing so on balance helps to stabilize or destabilize the world. The virtues and vices of America’s global role have been debated for the best part of a century. Fewer and fewer people alive today can recall a world in which the military, economic and cultural power of the USA has not been an overwhelming global reality.

America’s imperial heritage is the historical key that explains why opinions are so strongly divided. Understanding how a nation that was born out of its anti-imperialist stance would end up adopting its very own imperial practices is a complex matter. By kicking out the British Empire, the fledgling American nation made the repudiation of its imperial inheritance a pillar of its self-identity. Notions of freedom became essential to America’s national creed, whether this meant freedom of consumer choice, freedom from government oversight or freedom from tyranny.

At America’s birth as a nation, the cause was unambiguous: freedom from the clutches of colonialism. However, traces of imperial DNA remained. Contradictory impulses, ignited in its past, still smoulder deep in America’s heart, and they continue to shape its domestic character and its foreign-policy debates.4

This became clear as its power grew across North America and then around the world. In a burst of continental conquest, America captured lands between the Atlantic and the Pacific Oceans. Native Americans, Mexicans and European imperialists alike were kept out or swept aside. Liberty was denied to African slaves and their descendants. Starting in the nineteenth century, America’s military began to wage a succession of wars of choice in far-flung lands. Its annexations and conquests stretched from Cuba to the Philippines. These American soldiers were unknowingly starting a military tradition of securing their country’s interests by fighting in distant lands.

The tradition endures for America’s ‘imperial grunts’, who now fight and die not for colonies, but for outposts from which the USA can exert global influence.5 ‘From the shores of Tripoli to the halls of Montezuma,’ begins the US Marine Corps Hymn: Tripoli refers to the First Barbary War in 1805; Montezuma to the Mexican-American War in 1847. By remembering past wars, new US Marine recruits are reminded that they are expected to fight abroad today. Waging war abroad, for good or ill, has been essential to American military culture.

This has enabled America to stand tall at key moments in global history. During the Second World War, and again at the Cold War’s finale, America appeared to be leading the world away from tyranny. Helping to reconstruct Western Europe and Japan after 1945, and presiding over the spread of democracy east of where the Berlin Wall had fallen in 1989, have been high points. These are the moments in history when America’s heady mix of wealth, military clout and self-professed moral authority have positively altered the destinies of people far and wide.

These same compulsions have also led to disastrous interventions in Vietnam in the 1960s and 1970s, and Iraq in the 2000s. Two different generations have now witnessed America’s military flounder in ill-begotten wars, each with the expressed intention of spreading democracy abroad.

Over a long span of time in world affairs, there can be no such thing as consistency of purpose or outcomes in the way America has defended its understanding of the free world. Inconsistency, however, seems endemic.

From invading Iraq, to its refusal to act decisively in Syria, America’s global posture has lurched between dramatic over-engagement and equally dramatic under-engagement. After 2011, when the Syrian dictator Bashar al-Assad began to massacre his own people in that country’s civil war, America remained on the sidelines, demanding that Assad step down, but not forcing him to do so. While the world was hardly clamouring for another American regime-changing invasion, the policy debates in Washington DC conveyed a sense of war-wariness and a hesitancy to intervene. Syria’s war has raised an important question: if America cannot find effective ways to step in to punish those who are evidently unleashing evil, then who will? In the end, Russia’s military stepped in to back Assad in September 2015, helping his army to win.

The US finds that it is damned if it does, and damned if it doesn’t, get involved in the world’s problems. Some Americans might be puzzled at how their country’s expenditure in blood and treasure, with an annual defence budget approaching $700 billion, can be spent in maintaining world order when that very same world, in a pique of ingratitude, derides the USA as ‘imperialist’.

While the USA does not self-identify as an empire, it has become the embodiment of an informal empire. Its global reach includes: military bases dotted around the world; fleets of globally deployable aircraft carriers; strategic alliances on every continent; orbital satellites that guide missiles; technology innovations with global consumer appeal; and economic power underpinned by the USA dollar as the world’s reserve currency. The USA can dominate many parts of the world, or at least it can make its influence telling. For now it remains the country that can intervene militarily virtually anywhere to defend its vision of world order, and its notions of right and wrong.

Questions over whether America should be doing any of this have defined global politics for decades. They cannot be addressed without recourse to the origins of America’s compulsions to be a superpower, which in turn reside in its imperial legacies.

Frontiersmen and colonizers: America’s imperial experience

Relative to other places, the USA is a young country – although it has existed for nearly a quarter of a millennium, which is more than enough time for successive historical influences to have accumulated, each leaving its mark on the country’s development.

With a little historical imagination, it is possible to picture the panorama of America’s expansion. From English settlers establishing the Jamestown (Virginia) and Plymouth (Massachusetts) colonies along the east coast in the seventeenth century; to the Independence War that cast off the shackles of British rule in the eighteenth century; to the USA’s expansion past the ‘Wild West’ and its incorporation of Texas, New Mexico, California and other states in the nineteenth century – a colonizing drive for continental control is the opening chapter in the American national story.

Empire is what the USA escaped from, and empire is what the USA later became. Not that you would know this from the way America has usually recited its own national story. As the Thirteen Colonies broke free from the British Empire, they birthed not only an independent country, but also a formidable founding myth.

The Boston Tea Party on 16 December 1773, when the Sons of Liberty revolted against British taxation, escalated into a full-blown insurgency. What followed is retold as the stuff of pure American patriotism. To invoke ‘the spirit of 1776’ is to summon an emotively powerful history that has passed into legend. Thomas Jefferson, the Founding Fathers and the Declaration of Independence intoning that ‘all men are created equal’ have provided the USA with its moral guiding light as an incubator of freedom. General George Washington’s crossing of the Delaware River at the Battle of Trenton in 1776, immortalized in the iconic painting by Emanuel Leutze, is a potent visualization of plucky, freedom-seeking rebels striving against tyranny. British soldiers and their allies were sent packing, and in 1783 the USA was recognized by Britain as an independent country.

Americans have tended to interpret the founding myth in creationist terms – not religiously, but in the sense of their nation having arisen from sudden and seismic events, rather than having evolved with roots and antecedents that stretch back far further.6 In this sense, America’s institutions and ideals were painted onto a blank canvas. It was ‘year-zero’ in 1776, and questions of inheritance were less compelling than the idealism of a fresh start. As George Washington said in 1790: ‘the establishment of our new Government seemed to be the last great experiment for promoting human happiness’.7 The sentiment has stuck in terms of providing an undergirding for American patriotism.

Historians have pointed out that the events of the Independence War do not really offer a basis for extrapolating a lasting sense of national mission. Some historians are rather more blunt than others. Hugh Bicheno is unapologetic: ‘Unfortunately it remains true that any criticism of the US is likely to be answered with a recitation about how much worse everywhere else is and always has been, a reflex drawing much of its vehemence from the Foundation Myth. One definition of immaturity is an inability to grasp that one’s birth did not transform the world.’8 Ouch! Is this at all fair?

The War of Independence was no straightforward fight between plucky rebels and a nasty colonial overlord. The USA was born from a competition between rival European imperial powers over North America, which was both a valuable prize in itself and a gateway to the Caribbean, to Central America and eventually to the Pacific Ocean.

When the Thirteen Colonies revolted against the British Empire’s terms of trade, the French and Spanish empires were watching carefully. As George Washington’s military campaign gathered momentum, France stuck in its oar, allying with Washington’s rebels in 1778. Spain joined the fray the following year. Franco-Spanish naval actions challenged the Royal Navy, hindering its ability to blockade the rebels. On land, French forces played a role in wearing down the British. The British themselves were reliant on local allies and imported Hessian (German) troops. As befitted an imperial and not a national age, the fighting forces were a patchwork of professional soldiers, mercenaries and locals who happened to be caught up in the swirl of violence.

As well as an imperial war, it was also America’s first civil war. A brutal schism tore American Patriots apart from the Loyalists to Britain’s crown. Black soldiers and Native Americans were involved on both sides. The war was brutal, and whereas America’s independence myth emphasizes the cruelty of British soldiers and the high-minded ideals of the Patriots, both sides fought bitterly. Violence, as well as Britain’s imperial overreach, was central to America’s birth.9

Paris, appropriately, was the location of peace negotiations that culminated in the November 1783 withdrawal of Britain’s troops from New York. The USA was hewn from the rocks of imperial competition between Britain, France and Spain.10

The territory of the US recognized at the Treaty of Paris had boundaries from the Atlantic coast to the Mississippi River. Benjamin Franklin, negotiating for the US, wanted parts of Canada, which Britain refused to cede. The Spanish remained in Florida and the French in New Orleans. Mexico lay to the south-west, and Native Americans across the plains. Next to this, the Thirteen Colonies looked rather puny and vulnerable. The USA’s success was far from a given at the outset.

This is where imperial legacies began to have a telling influence. The Patriots who waged the Independence War had rebelled against what they saw as the British Empire’s malpractice, not against the principle of empire itself. This was still the imperial age, and the fledgling USA would need to find its feet in a world of empires. What transpired is striking: the basic imperial template, in which a metropolitan centre coordinated affairs between a collection of far-flung and autonomous outposts, became the template for America’s westward expansion.11

Repudiating and then effectively replicating empire embedded a paradox deep into the American psyche. The implications of this became ever more telling as the USA found its feet.

Thomas Jefferson, then a delegate to the Continental Congress, had a guiding hand in the drafting of the Declaration of Independence and coined the phrase ‘Empire of Liberty’. It was uttered in 1780, while the war against the British was still being waged. He characterized the Empire of Liberty as ‘an extensive and fertile Country’ that would busy itself with ‘converting dangerous enemies into valuable friends’. Jefferson’s motivations were to differentiate America’s intentions from the European colonizers, and it was a neat phrase that remained in America’s conscience. It would later be employed to suggest the USA’s expansion was being pursued in the wider interests of humanity.

Jefferson later served as president (1801–9), presiding over a major act of expansion with the Louisiana Purchase of 1803. France, then embroiled in its own revolutionary war, and having purchased Louisiana from Spain only six years earli...