eBook - ePub

Histories of the Unexpected: The Vikings

Sam Willis, James Daybell

This is a test

Share book

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Histories of the Unexpected: The Vikings

Sam Willis, James Daybell

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Histories of the Unexpected not only presents a new way of thinking about the past, but also reveals the world around us as never before.Traditionally, the Vikings have been understood in a straightforward way - but the period really comes alive if you take an unexpected approach to its history. Yes, ships, raiding and trade have a fascinating history... but so too do hair, break-ins, toys, teeth, mischief, luck and silk!Each of these subjects is equally fascinating in its own right, and each sheds new light on the traditional subjects and themes that we think we know so well.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Histories of the Unexpected: The Vikings an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Histories of the Unexpected: The Vikings by Sam Willis, James Daybell in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & European History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

• 1 •

KEYS

Viking Age key found in Ellesø Skovsø, Denmark

Viking keys are all about control…

Keys as a security device have a history that stretches back more than 6,000 years, and in the Viking Age the technology and complexity of locks developed significantly. During this period, we see a wide variety of sizes and designs of keys, both simple and ornamented. In Viking society, keys were a signifi-cant source of power for the people who controlled them.

THE VIKING HOUSEWIFE

In particular, the key has long been interpreted as a symbol of power for the Viking housewife. They would wear keys on chains outside their dresses as a sign of their domestic responsibility and position. Tales of married women carrying such keys are everywhere in saga literature. The poem Rígsþula cites ‘a key-hung maiden / in goat-skin kirtle’ on her way to be wed in her ‘bridal linen’, the key symbolizing her future married status. Legal tracts dating from the twelfth and thirteenth centuries such as Borgartingslova speak of a housewife’s right to have the keys to the household, and archaeological evidence shows that women were buried with keys among their grave goods. For many historians, these ‘female’ keys represent a source of women’s authority within the household: the ability to control and restrict access to domestic spaces, to secure possessions and goods.

Rígsþula

This poem, which survives in a fourteenth-century manuscript, tells the tale of the Norse god Ríg, the father of mankind. He wanders the world and fathers three classes of humans: serfs, free-born farmers and nobles. The poem therefore contains valuable information about the living conditions and customs of the different social classes in the Viking world. The poem is particularly enigmatic, as the conclusion has not survived the centuries and it abruptly cuts off.

SYMBOLIC POWER

Some of the keys that have been recovered from Viking graves, however, were actually unusable. In a way these pose historians with a problem, but if we view the locks they opened as figurative rather than literal, then we can see these keys as providing the power to open doors from one sphere to another – perhaps from childhood to adulthood, or from life to death.

It is no coincidence that keys have been found in numerous Viking Age children’s graves in Sweden, something archaeologists believe is connected to passing into other realms. Symbolically, keys have also been associated with the power of prediction, and this is certainly how researchers have interpreted some of the keys found in the graves of women and children – with the key as a way of unlocking other worlds and looking into the future to see what changes that will bring. Viewed in this way, women who carried keys were not simply housewives, but carriers of knowledge, itself an important form of power.

Keys could also function as cultic or religious icons, a link which is made clear in the poem þrymskviða, where the key is connected to the female goddess Freyja, wife of Odr. In the poem, Thor dresses up as a bride instead of Freyja in order to trick the giant Thrymr. Assuming her clothing, Thor importantly ties Freyja’s ‘housewife’s keys’ around his waist. The deception works, no doubt thanks to Thor’s careful attention to detail.

Through its association with Freyja, the key is much more than a physical means of access to the household; it represents the role of Viking women as leaders, child-bearers and in the afterlife. Freyja appears in Norse mythology as ruler in the hall of Sessrúmnir in the meadow of Fólkvangr, where half of those who die in battle go. As the key-bearer, she is therefore a keeper of the dead in the afterlife. She is also a goddess of fertility, and figures in Norse mythology as a helper of women in labour. In the realm of childbirth, the key was viewed as a device to unlock women’s loins, and it was also a pre-Christian symbol of female fertility and motherhood.

KEYS AND VALUABLES

While there may be something in the symbolic meanings of keys in the Viking Age, it is their practical functions that offer us glimpses at how power was exercised. The key itself betrays an ancient instinct to protect property. Viewed as functional objects – in close association with doors, boxes, chests and trunks – keys and locks were intimately linked to privacy, wealth and authority. They gave people the power to lock valuable objects away – to control their use – whether these be weapons, precious metals or even textiles.

Importantly, it was not just Viking women who owned keys: they also appear among the grave goods of men, as well as in settlement and urban sites where they are discovered as single finds. The surviving keys and their accompanying locks are enormously varied in design, but they are typically made of iron and copper alloys and would have required significant artistic and technical skill to produce.

A comparison of keys found at the sites of Gotland and Birka suggest that there may have been differences in the design and uses of men’s and women’s keys. Archaeologists have argued that keys buried with women tend to be much simpler and more functional, while men’s keys on the whole have more ornate handles – some of which depict images of powerful birds – and more intricate tines or teeth. It is believed that, while women’s keys tended to open doors – and so are connected with space and the home – men’s were used for padlocks or chests, to secure weapons and valuables.

Birka

Situated on the Swedish island of Björkö – just off the coast of Stockholm, in Lake Mälaren – Birka was an important Viking city of between 500 and 1,000 inhabitants. Founded in around 750, it lasted for about 200 years until it was abandoned in 975. It is one of the most important archaeological sites in Scandinavia, and sheds crucial light on the development of Viking trading networks.

WEAPONS AND TREASURE

An astonishing number of fragments from around forty-four padlocks were found at Birka in Sweden, at the site of the fortified garrison building popularly known as the ‘Hall of the Warriors’. Thousands of arrowheads were also found at the site, which further suggests its military connections, and hints that it came under sustained attack at some point. The padlocks were of Norse production and were used to protect this site, perhaps securing chests containing bows, swords, axes or arrows. From among the fragments are a number of smaller and weaker locks that would have been very easy to break, rather like the kind of locks on a modern-day secret diary. These smaller locks were probably ceremonial rather than for security – used where it was important to seal something symbolically. The question of who had access to the keys to these locks therefore became about power and hierarchy.

One of the finest examples of a locked Viking chest containing valuables comes from the Cuerdale Hoard. Discovered in the spring of 1840 on the banks of the River Ribble in Lancashire, the lead-lined chest contained some 7,500 silver coins and great quantities of other silver jewellery and scrap (or ‘hack’) silver. Around forty kilograms of silver in all, it is the largest-known Viking hoard in the West, and worldwide it is only surpassed by a handful of discoveries along the ancient Arabic silver route into Russia. The hoard, which dates from c.904, contains coins and jewellery from all over the Viking world: Scandinavia, Francia, Italy, Ireland, Pictland (now part of Scotland) and England. It is believed to be the loot of a Viking army, and its location in the north-west of Britain has led historians to link it to the expulsion of the Vikings from Dublin in 902, as some of them settled in what is now Lancashire.

• 2 •

GRAFFITI

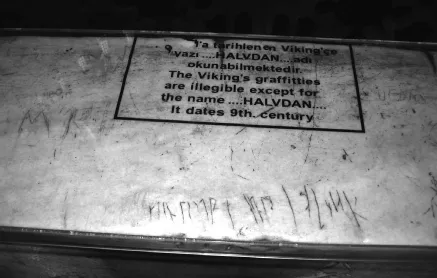

Runes featuring Nordic names dating to the ninth century, found in the Hagia Sophia, Istanbul

Graffiti is all about Viking travel...

Viking Age graffiti takes many forms – from rough marks, names and short phrases carved in runes, to complex symbols and pictures. In a world where paper was scarce, inscribing onto stone, wood or metal was an important form of literary expression – and, in combination with other sources, graffiti even enables us to study Viking travel around the world.

CONSTANTINOPLE

One of the most important sites of Viking graffiti is the mosque of Hagia Sophia in Istanbul (formerly Constantinople), which contains not only runic inscriptions but also images of four Viking ships dating from the second half of the ninth century to the early part of the tenth century. These carved markings testify to contact between Scandinavia and Byzantium, two giant maritime cultures of their time.

The Hagia Sophia

Built between 532 and 537 on the orders of the Byzantine emperor Justinian I, the Hagia Sophia (meaning ‘Holy Wisdom’) was an Eastern Orthodox Christian cathedral in Constantinople. The building’s iconic central dome is more than fifty-five metres in height and more than thirty metres in diameter. It became a mosque in 1453, when Ottoman forces captured the city.

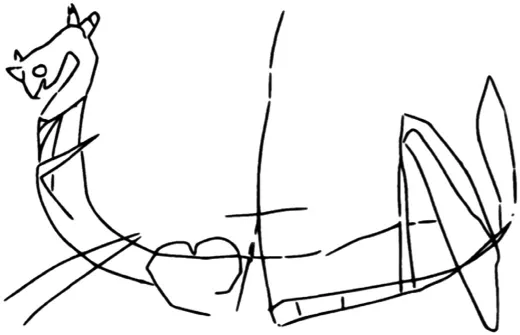

Sketch of a graffito of a Viking ship found in the Hagia Sophia

Scratched onto the walls of the second-storey aisles and galleries, the images clearly depict a variety of seagoing cra that are distinctly Viking in design – with long, narrow hulls – and are similar to ship graffiti discovered over 2,000 miles away in a church in Fortun, in the west of Norway. The most distinctive image is in the south gallery of the mosque, scratched onto the north-west column. It depicts a traditional longship with a dragon-head prow, which has been interpreted as a warship belonging to a wealthy man.

We know from archaeological and literary sources that there was indeed significant contact between Scandinavia and Byzantium from the ninth century onwards. Northerners (widely referred to as ‘Varangians’) made their way to the lafter’s capital city of Constantinople through the mediation of the Kievan Rus, and stayed to fight in the Byzantine army in their many wars against the Emirate of Crete and the Arabs in Syria. And they came in large numbers – in 988, Prince Vladimir of Kiev sent no fewer than 6,000 Vikings as military muscle to fight for the Byzantine emperor, Basil II. This force later formed the core of the Varangian Guard, a fearsome band of troops whose role was to defend the emperor.

The Kievan Rus

A loose confederation of tribes under Scandinavian rule who inhabited an area between the Baltic and Black seas between c.880 and c.1240, with the main power base in Kiev. At its height, the majority of th...