Let us start with the Chinese currency, renminbi (or yuan, as it is called locally), as it is probably the most controversial issue in the global system during China’s structural transformation. The price in which Chinese goods and services and assets are valued not only influences the attractiveness of the Chinese markets for the rest of the world but also global competition for export market share and capital allocation.

By unleashing its 440-million-strong cheap labour force and keeping the renminbi undervalued in the 1990s and the early 2000s, China became the world’s factory and attracted foreign direct investment (FDI) from all over the world. However, as the supply of cheap labour falls and wages rise over time, the yuan has also become expensive. The forces behind China’s structural transformation will manifest themselves in mega trends that will change China and its relationship with the global system for decades to come.

No More Cheap Yuan

China has been gaining export market share steadily for many years, thanks to rapid productivity growth, cheap wages and an undervalued renminbi exchange rate. In fact, China’s export market share reached 12% of the world total in 2014 from less than 1% in 1980 when economic liberalisation in China started. During the same period, China also attracted huge amounts of FDI inflows from all over the world. Its real GDP growth rate averaged 10.4% a year between the mid-1980s and mid-2000s. This high-growth era was facilitated by financial repression (which artificially depressed the return on bank deposits for savers) and an undervalued renminbi that deprived households of consumption power and channelled national savings to state investment.

This development strategy produced a lopsided growth with excess savings feeding excess investment at the expense of private consumption. The resultant rapid build-up of output capacity made Chinese growth dependent on exports. In fact, the combination of rapid productivity growth in the 1990s and early 2000s and a cheap currency policy pursued by Beijing gave China’s export sector a significant boost and made it a crucial driver for domestic investment and economic growth. But the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2009 forced China to abandon this lopsided growth strategy as the crisis had decreased the world demand for exports, including China’s (see Lo, 2009, chapter 4).

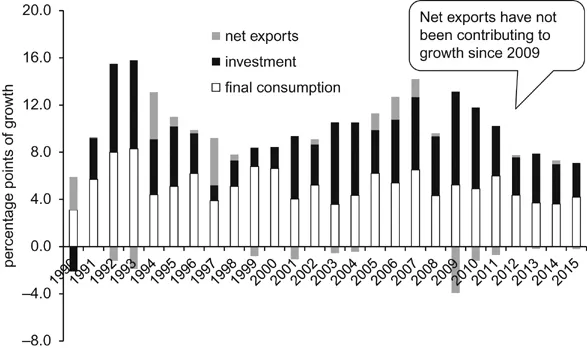

Since then, China has looked inward for growth sources through investment. Evidence shows that net exports have been a drag on, not a contributor to, China’s GDP growth1 since 2009 (Figure 1). This marks the beginning of a mega trend of China’s growth transformation from being export-led to domestic-led. Those who still argue that China would need to devalue the renminbi sharply to stimulate exports to generate growth are ignorant about China’s development and global development. The challenge for China is to manage the structural changes within the domestic sector from investment-led to consumption-driven growth in the coming decades.

Figure 1: Growth Contribution of China’s GDP Components. Sources: CEIC, Author.

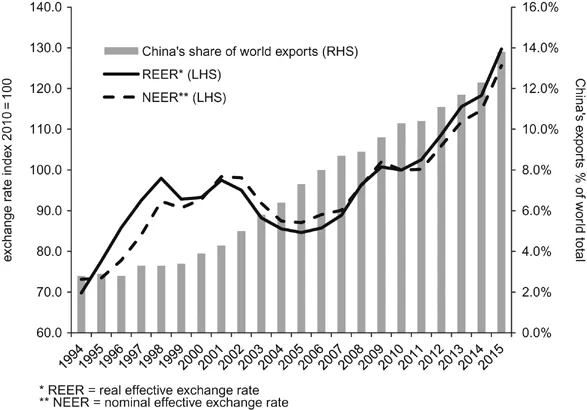

A dear currency does not help a country’s growth as it hurts exports. But contrary to conventional wisdom, in China’s case a cheap currency will not help Chinese exports and, hence, growth. This can be seen from the fact that despite an appreciating renminbi exchange rate (both in real and nominal effective bases) for more than 20 years since the mid-1990s, Chinese exports have kept gaining on global market share (Figure 2). This proves that the renminbi exchange rate was not a significant factor affecting Chinese export performance. Adding this to the fact that net exports do not contribute much to China’s GDP growth anymore, it is clear that renminbi devaluation will not help Chinese growth much.

Figure 2: China’s Global Export Market Share Continues to Rise Despite a Rising Renminbi. Sources: CEIC, WTO, Author.

Over the years, there have been political and market noises calling for Beijing to devalue the renminbi sharply (by 20–40%) in order to rejuvenate Chinese growth under the weight of its structural transition. After many years of balance of payments (BoP) surplus, China saw an unprecedented large BoP deficit (due to a shrinking current account surplus and a growing capital account deficit) between late 2014 and early 2016 for the first time in more than 10 years.

This prompted the People’s Bank of China (PBoC) to intervene heavily in the foreign exchange market to keep the renminbi from falling too sharply. This intervention created a passive liquidity tightening effect on the domestic economy and aggravated the weak growth momentum. Developing economies usually respond to such a situation by devaluing their currencies. Advocates of devaluation thus argue that China should do the same to regain export competitiveness and stem capital outflows.

Even if we accept for the moment the competitiveness argument of devaluing the renminbi, the comparison is fundamentally flawed. At the time of writing, China is the world’s second largest economy that runs the largest trade surplus in the world. Developing economies that devalued successfully were much smaller in size, which made it easier for the global system to absorb the increase in their exports. Evidence also shows that they devalued after their overvalued currencies had caused persistent large current account deficits.

There is no evidence of an overvalued renminbi (Cline, 2016). The main economic reason for Beijing to resist devaluing the renminbi, despite that fact that it has been the dearest currency in Asia since the mid-2000s, is that rather than boosting growth, a weaker currency makes a surplus country (in terms of its current account balance) more precarious. This is because in deficit countries, where domestic savings fall short of investment, slowing growth destroys foreign confidence and, thus, scares off foreign capital inflows. This, in turn, causes domestic investment to fall.2 Currency devaluation may help offset or cushion this negative impact on growth in deficit countries.

Devaluation reduces real household disposable income and, hence, consumption, so that the consumption share of GDP falls. By definition of national income accounting, the savings share must rise. This rise in savings can happen in several ways, but typically it happens because the devaluation increases the profitability of the tradable goods sector (i.e. exports), which increases the saving of this sector (in addition to the increase in household saving due to the fall in consumption). In other words, currency devaluation redirects income from consumption to savings. The rise in domestic savings reduces the country’s dependence on foreign capital and, thus, keeps investment from falling even when foreign inflows decline.

However, devaluation does not work for surplus countries the same way because they do not suffer from saving deficiency; and China’s national savings are excessive at 50% of GDP. Devaluing the renminbi would only depress the already-low domestic consumption and increase the country’s already-excessive investment and reliance on exports to release the excess capacity. The point is that for surplus countries, devaluation replaces consumption demand with investment demand and trade surpluses.

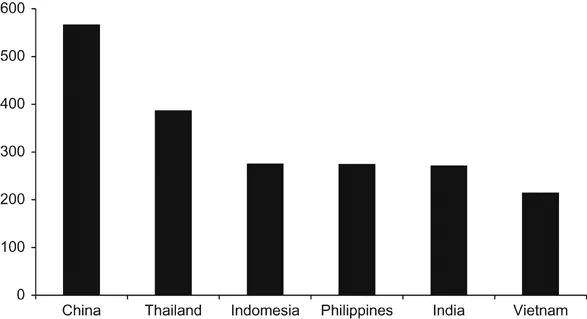

From China’s perspective, this certainly goes against the purpose of its economic rebalancing from investment-led to consumption-led which Beijing is striving to achieve. This gives it the incentive to resist renminbi devaluation. But keeping a stable, and dear, renminbi also means difficulties for China’s export sector, especially when it is losing the advantage of cheap labour cost to its Asian neighbours (Figure 3). Well, this is typically the cost of structural rebalancing.

Figure 3: Manufacturing Workers Average Monthly Compensation (2014). Sources: JETRO, Author. Note: This includes wages and mandatory social contribution.

From a global perspective, in a world with growing trade tensions and persistent weak demand, if Beijing pursues a devaluation policy that would boost China’s trade surplus, it may likely ignite more currency wars, encourage trade protectionism and risk turning back the process of globalisation. Assuming China does not opt for devaluation in its economic transformation process, Vietnam, India, Indonesia and the Philippines will likely be regional winners due to their cheaper cost of labour (see Figure 3).

Urbanisation and Demographics

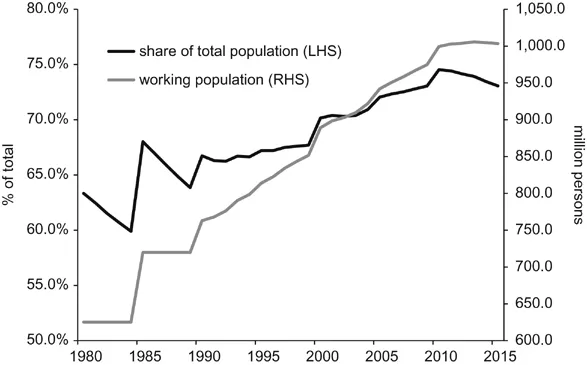

China’s working-age population (15–64-years old) ballooned between 1970 and 2010, fuelling double-digit GDP growth rates for four decades. But this is a thing of the past as its labour force as a share of the total population started to shrink in 2012; in terms of absolute numbers China’s working population started shrinking in 2015 (Figure 4). The United Nations projected that China would be adding more retirees than employees in the next two decades (United Nations, 2015). While China will remain the world’s most populous nation and will add another 40 million people by 2030, ceteris paribus, its demographic dynamics is certainly deteriorating. As the baby-boomers age and they haven’t produced enough children to replace them, a circle of rising wages, declining demand and falling savings rate will reduce potential growth. This will also put more pressure on fiscal spending to support the ageing population.

Figure 4: China’s Shrinking Work Force (15–64-Years Old). Sources: CEIC, Author.

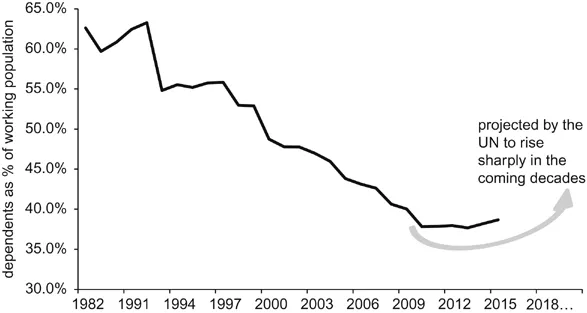

After declining for decades, China’s dependency ratio (the numbers of young (0–15-year olds) and old (over 64-year olds) people as a share of the working-age population) is poised to rise sharply again (Figure 5). The median age will rise to 41 in 2025 from 37 in 2015, according to the United Nations projections. But Beijing is aware of this population ‘time bomb’ and has implemented two measures since 2014 to cushion its impact.

Figure 5: China’s Dependency Ratio. Sources: CEIC, Author.

The first is relaxing the hu kou3 (or household registration) restriction in 2014 and the second is changing the One-child policy4 to a Two-child policy in 2015. Although the ultimate impact of these reform measures is expected to be limited, they show that the Chinese government was willing to make changes to address the impending economic problems.

Beijing issued reform guidelines in July 2014 relating to its decades-long hu kou system. The market saw this as a significant step towards increasing labour mobility and productivity gains and unlocking ‘dead capital’ (Lo, 2007, pp. 33–38) in the rural regions. In reality, the impact of this reform is likely to be very limited because to achieve the full benefits, China needs to scrap the system altogether. But Beijing knows that such a drastic move would face severe resistance and is thus implausible to implement in the short-term. So the reform guidelines were more a sign of incremental progress than a big step forward.

China has a dual hu kou system that has divided people into urban and agricultural households since 1958. Different hu kou holders enjoy different social benefits. Urban hu kou holders receive better education, medical care and pension than their rural counterparts, who are entitled to farmland use rights and are allocated rural land to build houses. A chapter in Beijing’s reform guidelines document says that China would set up a unified hu kou system by removing the rural–urban distinction. Some analysts have jumped to the conclusion that this would mean giving rural residents the same rights as urban residents in terms of employment, education, medical care and housing.

This is not true. The reform does not totally remove the rural–urban distinction and, thus, does not remove all the barriers to migration and labour mobility from rural to urban areas. The document states that a system of ‘residence permits’ would be set up to allow qualified migrants to enjoy urban services and social benefits. Whether a rural emigrant is eligible and to what extent he/she can enjoy these benefits depends on how long the person has lived in the city and how long he/she has contributed to social insurance programmes. Anyone who does not have a residence permit is still not entitled to equal urban benefits, whatever type of hu kou the person holds.

This dual hu kou system makes rural migrants feel discriminated against and hinders migration and, hence, geographical labour mobility within the country. The reform is trying to narrow the difference between the two types of hu kou and, hence, raise labour mobility and facilitate urbanisation. It is intended to be implemented initially in towns and small cities, where a resident who has lived long enough to get a residence permit can apply for an urban hu kou and enjoy urban social welfare benefits.

China plans to urbanise a total of 100 million rural residents and migrants5 by 2020. Official data show an urbanisation rate of 51% in 2015. This still lags behind the rate in many other countries which boast an average rate of more than 70%. Crucially, China’s genuine urbanisation rate is only about 32% when adjusted for the 260 million migrant workers, who work and drift between cities and never contribute effectively to urban spending (as they tend to save and send the money back to their hometowns). Granting residence permits to these migrant workers could effectively help boost GDP growth via investment and consumption spending.

Expanding the hu kou reform to its true form (i.e. eliminating the rural–urban difference and, eventually, the hu kou system altogether) is easier said than done. Urbanisation will require all levels of governments to spend more on social welfare and construction. However, under the current asymmetrical budget structure, local governments have to remit 100% of their fiscal revenues to the central government but only get 40% of that back in the form of fiscal transfer. Meanwhile, they have to pay for 80% of their fiscal spending. Thus, many local governments are financially strapped and are putting up strong resistance to the hu kou reform that would facilitate urbanisation.

Ultimately, the hu kou reform cannot succeed without parallel land reforms that allow farmers to trade their farmland and transfer land titles in the open market to unlock their ‘dead capital’. Medicare and pension programmes will also have to be unified nationwide so that people can enjoy equal services wherever they live in China....