![]()

CHAPTER 1

The Underlying Principles of Competency Modeling

This chapter will provide a fundamental understanding of the why, what, and how of competency modeling. Let us start with the observation that all organizations have a very practical need to identify the criteria that define their ideal employee. Any leader who makes decisions about whom to hire, whom to promote, what skills to train, or how to appraise, implicitly assumes this ideal criteria. Defining this model employee—and creating a blueprint to replicate him or her—is an ongoing challenge dating back thousands of years. Indeed, two millennia ago the Chinese bureaucracy identified its ideal member as someone who could pass rigorous tests on the six arts of arithmetic, writing, music, archery, culture, and horsemanship.

Competencies are now the most prevalent method used to define ideal employees and have become a fundamental part of talent management systems across organizations. Talent management has been defined by the Society for Human Resources Management as “the implementation of integrated strategies or systems designed to increase workplace productivity by developing improved processes for attracting, developing, retaining and utilizing people with the required skills and aptitude to meet current and future business needs” (emphasis added). Therefore, having a competency-based system to link these processes is the key to cohesive and effective talent management.

Historical Influences on Current Competency Constructs

Modern concepts of an ideal employee have roots in the assessment center movement, dating back to World War II. For hiring and promotion, assessment centers created behavioral definitions of competence, calling them dimensions or variables and then used simulations to test the readiness of candidates. This methodology, used first at the Office of Strategic Services (OSS, now the CIA) and then at the Bell System (now AT&T), created a better and more predictable way to select spies as well as supervisors.1

Because assessment centers relied on the real-time observance of performance in simulations, evaluators needed to reference very specific behaviors to allow reliable ratings. (For example, Presentation Skills could be broken down into behaviors such as eye contact, gestures, loudness, organization, and inflection). These behavior-based definitions were excellent in providing an efficient and effective method of review and propelled the popularity of this form of evaluation.

Over time, other talent management professionals were interested in more holistic views of the employee and generated specific job requirements based on the knowledge, skills, abilities, and other characteristics (referred to within the human resources profession as KSAOs) needed to perform well in a particular role. KSAOs could be used to define roles, and in a training context, provide learning objectives that could be framed in terms of knowledge gained or skills acquired (assuming that the individual had the required ability). Career counselors added values and motives to the mix as relevant variables when discussing potential positions and paths.2

The term competency really entered the talent management lexicon in 1973 when noted American psychologist David McClelland wrote the pivotal paper “Testing for Competence Rather than for Intelligence.”3 It was further popularized by McClelland’s colleague, Richard Boyatzis, and others who used the competency concept in the context of performance improvement.

Another influence on the evolution of modern competency modeling was Dr. Malcolm Knowles, and his seminal work in adult education and lifelong learning. Focused on what he called andragogy (i.e., adult learning versus pedagogy: childhood learning) Dr. Knowles referred to competencies as necessary segmentations in describing what was needed to perform in overall complex and cognitive leadership and life roles.4 He noted that in order to facilitate learning it was absolutely necessary to parse broad learning agendas such as teaching leadership into component parts such as Communications Skills or Delegating. In his listing of needed worker competencies, one can see the beginnings of several modern universal competencies such as Organizing and Planning and Relationship Building (see Table 1.1).

Table 1.1 Malcolm Knowles’ original worker competencies

| Worker competencies |

| Career planning |

| Using technical skills |

| Accepting supervision |

| Giving supervision |

| Getting along with people |

| Cooperating |

| Planning |

| Delegating |

| Managing |

While not working directly in the corporate world of selection and development Dr. Knowles distinguished reputation, and his independent and simultaneous use of the term competency provided credibility and acceptance.

A final competency influence came from the worlds of personality and trait research and the paper-and-pencil (now mostly online) testing associated with them. Thousands of individual tests were developed to measure hundreds of various cognitive and social constructs such as intelligence, personality traits, values, attitudes, and beliefs. For example, one of the world’s most popular personality instruments, the Myers–Briggs Type Indicator, measures, among other things, an individual’s personality preference for extroverted or introverted behaviors. Another is the Watson–Glaser test, which measures critical thinking and is correlated with general intelligence. This entire body of testing knowledge creates an additional, very comprehensive resource to help explain underlying influences on behavior.

Defining Competencies Today

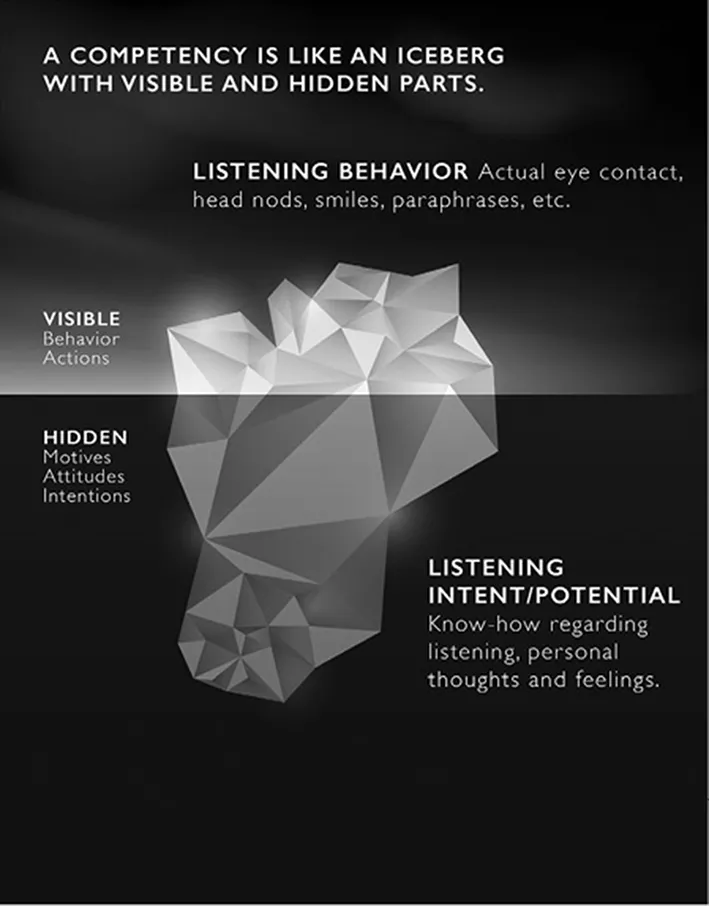

Despite lingering debate around definitions,5 professionals concur that a competency serves to connect these various influences into a single construct, with the “primary definitional element being a behavioral or performance description.”6 Thus an individual competency describes a specific set of behaviors or performance indicators associated with a facet of exceptional performance in an organizational role. Each competency reflects a unique combination of knowledge, skills, abilities, and other factors that are driven and influenced by multiple traits and motivations, ultimately manifesting themselves in skillful behavior. A competency model refers to a complete set, or collection, of different competencies that are applicable to a single organization, or more generically, to every organization. Ultimately, competence is manifested in explicit behaviors (what you do and how you show up) and performance (decisions, actions, and results); while intent and potential are part of the much more complex, and largely unseen, world of values, traits, and motivations (the O in KSAOs).

Active Listening is an example of a competency associated with many models. The definition includes behaviors such as eye contact, head nodding, verbal affirmations, smiles, and accurate paraphrasing or summarizing. How one is judged in this competency depends on knowing how to listen and also having the motivation to listen. (Do I value other people’s opinions? Am I curious about their experiences and feelings?) And while active listening may be a globally applicable concept, the types of behavior that illustrate effective performance have a cultural context that must be factored into local behavioral definitions. For example, in some cultures listening is important, but looking directly at those in positions of higher authority is considered disrespectful. Figure 1.1 illustrates the visible and hidden elements in Active Listening.

Figure 1.1 A simple representation of the concept of a competency

Comprehensive competency models offer an integrating framework that provides an essential foundation for key human resources processes, offering a complete menu of dimensions that can be sorted for individual organizational roles and levels. Figure 1.2 shows one commercially available competency model that includes 41 competencies distributed into seven clusters.7 This model presents a complete set of competencies that can be sorted by function and level in an organization.

Figure 1.2 Universal competency model

Source: Based on the Polaris Competency Model® 2014 Organization Systems International

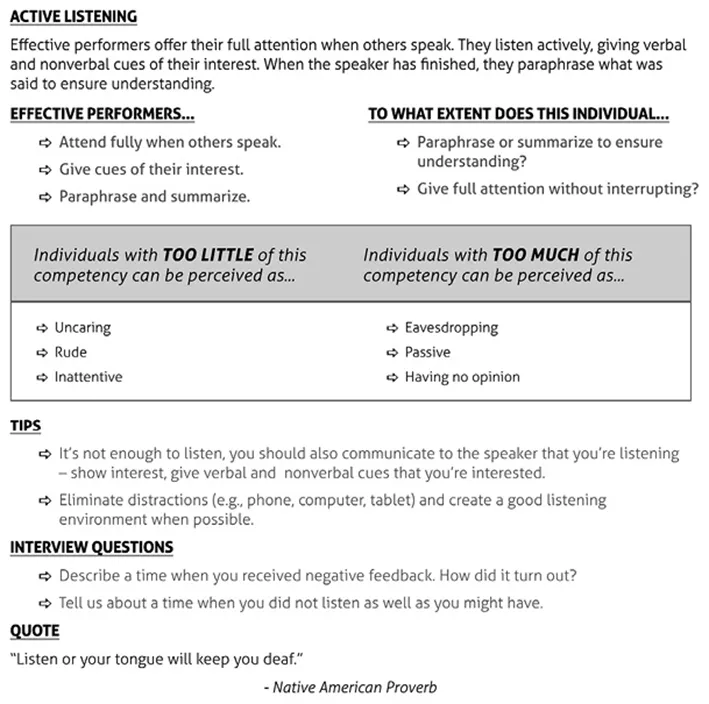

Figure 1.3 is an example of a detailed definition of the Active Listening competency within the Communications cluster.

Figure 1.3 Competency detail (Active Listening)

Issues to Consider When Developing Competency Models

Several issues need to be addressed to fully understand, and more importantly apply, any given competency model:

1.The need for reliable and valid models and measurements

2.The necessary complexity and need for context of any given model

3.The decision to define competencies in terms of behaviors or motives and traits

4.The number of competencies that should be included in a model

5.The equality or relative weight of any given competency.

The Need for Reliable and Valid Competency Models and Measurements

When developing criteria (and any accompanying test or measurement of that criteria) it is essential to insure that accepted thresholds of both reliability and validity are met. This is especially important because models, and associated measurements, are typically used to select, appraise, and promote individuals and must be legally defensible. But even more importantly, measures of reliability and validity define how efficient and effective a measure is, and ultimately whether any investment in models and measurements is worthwhile.

Reliability means that a test or measure produces consistent individual results over time and from person to person. Validity means that a test accurately measures what it purports to measure—that is, it can be used to predict behavior. It follows that validity will be problematic for any measure that is not first reliable.

A s...