![]()

1

The Army of the North

In 1870 Dr Achille Testelin was a successful physician practising medicine in Lille. Born in 1814, he had been an active member of the Republican opposition during the reign of Louis Philippe. He sat as a Radical in the Legislative Assembly until the coup d’état of 1851. Following this he was, as a spirited opponent of the new Imperial regime, expelled from France. He made his way to Brussels, and practised there until 1859, when the amnesty of that year enabled him to return to France. He took no active part in politics but remained a staunch Republican.

With the overthrow of the Second Empire, he was, as a personal friend of Leon Gambetta, an obvious candidate to take up a responsible position under the Government of National Defence, and he was first appointed Prefect of the Department of Nord, and later, on September 30, as Commissioner for the four Departments of Aisne, Nord, Pas de Calais and Somme. He threw himself energetically into the business of organising the defence of north-eastern France. He faced almost insurmountable administrative and financial problems as he went about the task; but he soon proved that his had been a wise appointment, as he brought intelligence and vigour to the governance of the area for which he was responsible.

The fall of the Second Empire, and the proclamation of a Republic, had left the administration of government in a state of doubtful legality. Clearly, given the prefectorial system by which France was managed, steps had at once to be taken to appoint, as prefects of the departments of France, men who could be relied on to support the new regime and to carry its policies into effect. The scramble for office on September 4 had ended with the 33 year old Leon Gambetta in position as Minister of the Interior, and he was soon confirmed in that post. By September 14 he had appointed new prefects to 85 departments:

The list of appointments was an illuminating comment upon the make up of the Republican party. Like master, like man: as the majority of the Government of National Defence were either journalists or lawyers, so no less than 44 of the new administrators were, or had been, lawyers, while 14 were primarily journalists. These men, who were to be the keystone of administration in the provinces, were appointed as Republicans, and they seldom failed to show strong party spirit.1

A sense of the need to give the government of the provinces some democratic legitimacy had led to a decree on September 17 that municipal elections should be held on September 25 followed by constituent elections for a National assembly on October 2. The date for the latter was brought forward from October 16. The decision to hold municipal elections was greeted with dismay by the newly appointed prefects, including Testelin, who telegraphed: ‘Your decree concerning municipal elections is our ruin! You will see all the former Ministers and members of the majority return at the head of the list.’2

By now the risk of Paris being cut off had led to a Delegation of the government leaving Paris for Tours. It was headed by Adolphe Cremieux, the 74 year old Minister of Justice, acting with Alexandre Glais-Bizoin, and Admiral Fourichon, the Minister of Marine, and they too protested at the proposed municipal elections. Gambetta was adamant; but since elections could scarcely be held without an armistice, and the talks aimed to achieve this held between Bismarck and Jules Favre on September 19 and 20 proved abortive, it was found necessary to postpone the constituent elections indefinitely, as well as the municipal elections in Paris. The latter decision enabled the Delegation to take the same step in relation to the provincial municipal elections, and the prefects were instructed to deal with the matter by ‘the maintenance of the existing municipalities or by the nomination of provisional municipalities.3 In this way the prefects were able to ensure that a proper Republican constituency could be maintained.

The Delegation, however, now overreached itself by announcing on October 1 that after all constituent elections were to be held in the provinces, in order to reinforce their authority. In Paris, the remaining members of the government were outraged, pronouncing that any such elections should be null and void. Gambetta, who had proposed this, argued that ‘a man of energy’ should be sent to Tours. On the night of October 1 no agreement could be reached on who should go. Since Paris was now more closely invested than the French leaders had expected, the journey could only be made by balloon, and was obviously not without risk. As Foreign Minister Jules Favre had a need to be able to contact foreign governments, and was an obvious choice. Perhaps on the ground of his age – he was 61 – he firmly declined; and the lot fell on the 32 year old Gambetta. After a show of reluctance he allowed himself to be persuaded, and at 11.00 am on October 7 the balloon Armand Barbès rose from Montmartre carrying Gambetta, Eugène Spuller, his secretary, and the pilot Tricker. It proved to be an adventurous voyage. A mistake by Tricker caused the balloon to descend rapidly, and it touched the ground before rising again to 2000 feet. The danger was not over; near Creil it had come down to 500 feet over a party of German troops before rising again as they opened fire. Gambetta’s hand was grazed by a bullet. The balloon finally passed over the German lines near Montdidier, coming to earth in a forest, from where that evening Gambetta reached Amiens.4

Gambetta. (Private collection)

Gambetta’s escape transformed the situation at Tours. Arriving there soon after noon on October 9 he was, within an hour, in conference with his colleagues. One of the first decisions to be taken was to fill the vacant post of Minister of War, and Gambetta decided to take it himself. Both Crémieux and Glais-Bizoin objected; but Gambetta brought with him the right to two votes in any dispute and Fourichon gave him his vote also. Before nightfall he issued his famous circular to the people of France. In it he gave a distinctly upbeat account of the situation of Paris and of the courage and determination of its defenders, as JPT Bury noted:

If the truth of his conclusion – ‘Paris is impregnable; it can neither be taken nor surprised’ – had yet to be proved, it was nonetheless true that the situation and efforts of the capital imposed very definite obligations upon the citizens of the departments: of these the first he declared to be to wage war to the knife, the second – ‘to accept as a father’s the commands of the Republican authority which has sprung from necessity and from right.’5

Gambetta went on to assert that if the Republic was to be preserved, France must repeat the miracle of 1792 and drive back the invader. He ended with a ringing appeal to the French people:

The Republic appeals for the aid of all citizens; her Government will consider it a duty to employ every brave man and to make use of every talent. It is her tradition to arm young leaders; we shall find them ... No, it is impossible that the genius of France should be veiled for ever, that the great nation should be deprived of its place in the world by an invasion of 500,000 men. Let us rise up, then, en masse, and die rather than undergo the humiliation of dismemberment. Through all our disasters and beneath the blows of ill fortune we still preserve the idea of Fench unity and the indivisibility of the Republic.6

One of the talents that Gambetta was keen to utilise was that of General Bourbaki, who arrived at Tours on October 15 after his abortive visit to Hastings to visit the Empress Eugénie in pursuit of a possible settlement. Bourbaki, who told Gambetta that Bazaine and his army shut up in Metz still recognised Napoleon III, offered his services to the government, and Gambetta, who was very impressed by him, invited him to take command of the Army of the Loire that was assembling. The two men had immediately taken to each other, although Gambetta quickly reached the conclusion that Bourbaki’s strength lay rather in leading troops in the field than organising them for battle. For his part Bourbaki was dazzled by the young politician: ‘He bids the paralytics arise and walk, and behold the paralytics arise and walk.’7 Bourbaki, however, after appraising the hopelessly confused condition of the army and the enormity of the task assigned to it, was sufficiently clear sighted to be firm in his refusal of the post. As the British ambassador Lord Lyons reported to Lord Granville, he had found that the situation was impossible, not least because he ‘could not reconcile himself to serving under the eye and the immediate control of the men now at Tours.’8

In appointing commissioners to take charge of the various regions in which it was hoped that armies would be formed that would be capable of relieving Paris, Gambetta equipped them with the widest powers to mobilise all the material and human resources available, leaving them with as free a hand as possible. Testelin took full advantage of this. His immediate concern, of course, was to establish with the local military leaders a successful working relationship. Military authority in this region was the 3rd Military Division, and Testelin invested its commanders with all his powers to enable them to organise serviceable military units as a nucleus of an effective army. The results were a fearful disappointment; the officers concerned offered only the negative opinion that the most that could be hoped for was the defence of the fortresses. At the beginning of September the local commander was General Fririon; he was succeeded towards the end of the month by General Espivent de la Villeboisnet. Neither appeared to Testelin to provide the kind of inspiring leadership that would be required.9 Faidherbe, in his short history of the campaign in north-eastern France, described the state of the forces immediately available:

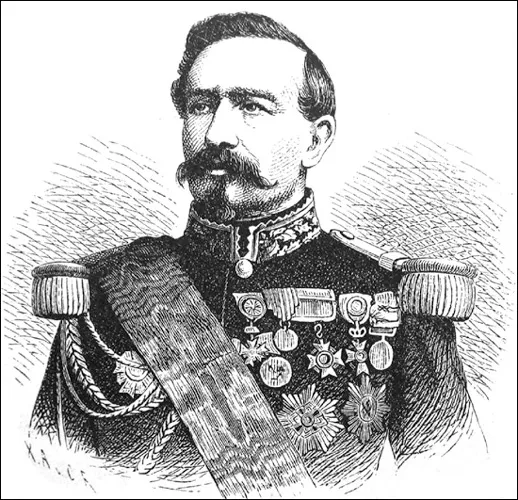

General Bourbaki. (Hiltl)

The improvement of the elements of the defence, which had been disorganised by the despatch of materials to Paris, was not sought. It sufficed to clothe and arm the Gardes Mobiles, without any concern about forming the proper staffs. As to the regulars, they had been drawn from seven or eight regional depots, and detachments from them had been despatched to the centre of the country to be absorbed into other units. Each depot had more than 1,000 men, with incomplete staffs of two companies. By way of artillery there was but one battery at Lille, and that incapable of service. Last, for cavalry the depot of the 7th Dragoons could with difficulty supply several troopers as escorts.10

Testelin was by no means content to leave matters in this state, and on October 15 he visited Colonel Jean Joseph Farre, the military governor of Lille. In him, he found a kindred spirit, and he lost no time in appointing him as a member of his Commission. Farre, who was born in 1816, was a career officer who was a distinguished engineer. He had been employed on a number of important construction projects, including Fort Nogent at Paris, and the works around Lyon and Algiers. He took part in the Kabyle expedition of 1857, and was chief of engineers at various times at Le Havre, Toulon and Rome. In 1870 he was director of engineering at Arras and Lille before serving in the Army of the Rhine; when it was invested in Metz he escaped and offered his services to the Government of National Defence, and was posted to Lille.11

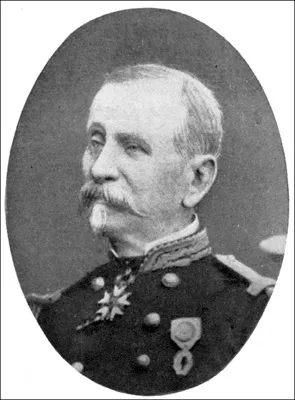

Lieutenant General Farre. (Rousset/Histoire)

Farre certainly fitted Gambetta’s specification of a suitable military leader; the latter strongly believed in the importance of engineers in the establishment of the new armies he was raising to fight the Germans. On October 14, the day on which he decreed that the Gardes Nationales should be embodied as an auxiliary army, he issued a separate decree which reflected that belief. Every department which had enemy forces within 100 kilometres of its borders was required to establish a committee of between five and nine persons. Under the presidency of the local military commander, it was to include an engineer officer, a staff officer, a road engineer and a mining engineer. This committee was to have wide powers of conscription, of commandeering supplies and of deploying the Gardes Nationales. At the same time Gambetta also set up an inspectorate to supervise these committees.12

Farre, like Testelin, recognised that there was no time to lose if anything approaching a worthwhile army was to be organised, and at once vigorously set about establishing the basic cadres from which units could be formed. Almost immediately he was faced by the defeatist indifference of the officers that constituted the 3rd Military Division, but in spite of this he soon began to make progress, as Faidherbe described:

The available elements were collected, former soldiers found from whom staffs could be established, an inventory was made of all material in the fortresses so as to understand their resources and more efficiently divide them; last, material was found for the immediate creation of provisional batteries. The zeal of the officials charged with this was stimulated by all means possible.13

Bourbaki’s refusal of the command of the Army of the Loire had been a great disappointment to Gambetta, but the latter was quick to identify in the nascent Army of the North an alternative opportunity to exploit the general’s talents. This post Bourbaki was prepared to accept. He was appointed on October 17 and he made his way northwards to Lille where he assumed the command of all the forces in the Region du Nord. Although the organisation of the army was still in a very primitive state, and his own morale was still low as a result of his experiences in Lorraine, he was not unmindful of the efforts which Farre ha...