![]()

Chapter 1

Who Was Ayn Rand?

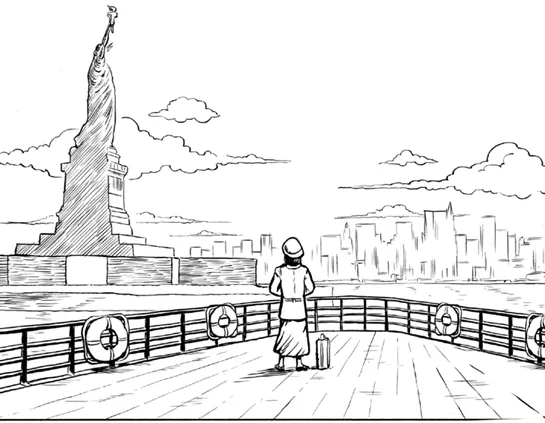

Ayn Rand was born in Russia in 1905. Her real name was Alyssa Rosenbaum. At the age of six, she taught herself to read. At age nine, she decided that fiction writing would be her career. She was twelve years old in 1917 when the Bolshevik Revolution began, which resulted in the Communists taking over Russia a few years later. The victory of the Communists led to the confiscation of her father’s pharmacy and years of severe poverty for the Rosenbaum family.

Ayn Rand knew from her childhood that she wanted to write fiction, because she wanted to write stories about heroes—about strong men and women who overcame any and all obstacles to accomplish difficult goals very dear to them. Such stories would echo the trajectory of her own life—in which she came alone to a foreign country, with little knowledge of English and even less money, and overcame every challenge to become one of the great novelists in the English language.

Shortly after she arrived in America, she moved to Hollywood to pursue a screenwriting career. She rented a room at the Studio Club, which provided living quarters for young women seeking careers in the film business. (Later, Marilyn Monroe, among many other future stars, lived there.) On her second day in Hollywood, Cecil B. DeMille, one of the great film directors in movie history, spotted her at the gate of his studio and offered her a ride to the set of King of Kings, the biblical movie on which he was then working. Struck by this young woman with the intense, dark eyes, he gave the young Ayn Rand her first jobs in America, first as an extra and later as a script reader.

A week later, while working as an extra on the DeMille set, she met her future husband, Frank O’Connor. The shy but determined Ayn Rand felt attracted to the handsome young actor, whom she later described as having an “ideal” face. During one scene, she made sure to place herself directly in his path so that he stumbled on her foot. He apologized, the ice was broken, and, as she put it years later, “the rest is history.” They were married in 1929 and remained so for fifty years, until Mr. O’Connor’s death in 1979. Their marriage took place shortly before the final extension of her visa expired, and led to one of the proudest days of her life—when she became a naturalized U.S. citizen in 1931.

Anthem was published in England in 1938, but was not published in the United States until after World War II, in 1946. Ayn Rand subsequently claimed that intellectual opposition among American publishers to its pro-individualist, anti-collectivist theme was the main reason it was not published in the United States until after World War II.

In the late 1930s, Ayn Rand began writing the book that would establish her literary reputation and bring her popular fame: The Fountainhead. It tells the story of a principled and brilliant young architect who struggles against virtually all of society—including the woman he loves—to build structures in accordance with his own vision and ideals. The hero, Howard Roark, who refuses to sell his soul in any form, has become an inspiration to countless readers over the nearly seven decades since its first publication.

This 700-page novel of ideas took Ayn Rand seven years to complete. But when it was done, Rand was convinced that she had a novel that was both serious and entertaining—one with both a profound theme and an exciting story. Unfortunately for her, many publishers did not agree. One leading publisher, for example, rejected the book on the ground that it was a bad novel. Another deemed it high-grade literature, but turned it down because it was too intellectual and controversial. By 1941, twelve publishers had rejected The Fountainhead. Finally, the editors at Bobbs-Merrill recognized what Rand had long believed about the book: it was a serious and entertaining novel that would sell. They published it in 1943.

The book that was supposedly too intellectual for commercial success has since sold, by conservative estimate, more than 6.5 million copies. Currently, The Fountainhead continues to sell well over 100,000 copies per year. It has achieved the status of an American classic, and is studied widely in secondary schools across the country.

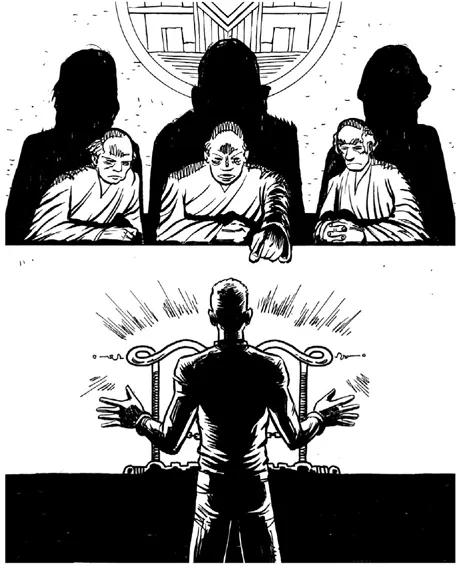

For years, her working title for the book was “The Strike.” Her answer to the question was that advanced civilization would collapse. In Atlas Shrugged, Rand composed a moral defense of capitalism, expressing a battery of related points: that an individual has the right to his own life; that he furthers his life by the use of his rational mind; and that a man’s right to think and live for himself requires a system of political-economic freedom, i.e., laissez-faire capitalism.

Rand discussed the possible publication of Atlas Shrugged with Bennett Cerf, one of the founders of Random House. He admired her novels but told her forthrightly that he found her political philosophy abhorrent.

Additionally, one of Cerf’s associates, Donald Klopfer, understood that her book’s proposed moral defense of capitalism would necessarily place her in opposition to thousands of years of the Judeo-Christian tradition in ethics—and said so. She was extremely pleased by his philosophical understanding, and answered, yes, it absolutely would. This did not frighten Klopfer or Cerf, but only made them more interested in the book. To Ayn Rand, it quickly became clear that Random House was the right publisher for Atlas Shrugged. And so, in 1957, the publishing giant released her greatest book.