1

The Age of Cortelyou

William McKinley and Theodore Roosevelt

Although disputes exist about when the modern presidency began, it had not yet appeared during the second administration of Grover Cleveland, from 1893 to 1897. In his approach to the office, Cleveland operated as the Buffalo, New York, attorney he had been before he entered politics in the early 1880s. The White House had no staff in the modern sense of the word. Cleveland worked with a single secretary, Henry T. Thurber, and a half-dozen clerks to conduct the nation’s business. By the end of his term, with his presidency in disarray after the congressional elections of 1894, Cleveland’s daily mail had dwindled to a trickle, and the pace of work slowed at the Executive Mansion.1

The president’s failure to deal effectively with the economic hard times arising from the Panic of 1893 left him with a divided Democratic party and a large residue of popular discontent in the South and the West. Threats against Cleveland’s life intensified security at the White House. By 1896, guards and rules kept the reclusive Cleveland out of public view, and the White House seemed a forbidding fortress. The president had no liking for reporters, and he sought to frustrate their efforts to learn what was taking place inside the government. “News-gathering,” wrote David S. Barry, a veteran reporter, was pursued “much after the fashion in which highwaymen rob a stage coach.” There were no facilities inside the mansion where journalists could work, and reporters waited outside in all kinds of weather to interview any important Washington figures who came to see Cleveland.2

The White House itself was a ramshackle building that was showing its age by the end of the nineteenth century. One observer said in March 1897 that “the perfect inadequacy of the executive offices to the present demands is apparent at a glance, nor is the lack of room less obvious at the social functions which custom as well as reasons of state impose upon the President.” In the midst of a severe economic downturn, there was no money for refurbishing the building and little thought of renovating the working areas to accommodate a more vigorous executive. On the verge of assuming world responsibilities, the presidency was understaffed, and the facilities at the disposal of the nation’s chief executive were minimal.3

That was how the American people wanted their president treated. He was “Our Fellow-Citizen of the White House,” not a dominant presence set apart from the rest of the country. The president was expected to hold regular public receptions where citizens could get in line to shake his hand and offer quick comments on his performance in office. At the same time, the chief executive could walk around Washington in relative safety on his own, without an impressive retinue of guards and handlers. The president was far from the national celebrity he would soon become. Pictures of William McKinley in 1901, for example, show the president sitting in his carriage with an aide but with few protectors anywhere in view. Although Abraham Lincoln and James A. Garfield had both been assassinated, there did not seem to be any credible threat of a repetition of such a tragedy as the nineteenth century neared its close.4

The dominant political trends of the day reinforced the impression of presidential irrelevance. Politicians saw the presidency as at most an equal branch of government with the Congress. For the Republicans, their roots in the traditions of the Whig party disposed them to regard a powerful executive with suspicion. As Senator John Sherman of Ohio put it, “The executive department of a republic like ours should be subordinate to the legislative department.” Although the record of Abraham Lincoln belied this position, Republicans saw the Civil War as justifying the need for a strong president in such perilous times but not thereafter.5

The Democrats, for their part, regarded presidential activism as largely negative in character and designed to prevent the busybody Republicans from spending too much and intruding on the private affairs of the average citizen. The precedent of Andrew Jackson ran through the Democracy, and Cleveland had been only the most recent example of a president who sought to prevent bad policies from being adopted. Even then, Democrats were suspicious of presidential strength. “The truth is,” wrote the Richmond Times in 1897, “all this idea of prerogative in the President is wholly out of place in our Constitution.”6

Two aspects of American life set the presidency in 1897 apart from the institution as it existed more than one hundred years later. The late nineteenth century was still in the heyday of the strong party system of American politics, which had dominated since before the Civil War. The electorate was more involved in partisan affairs, and allegiances to the Democrats and Republicans were intense. Newspapers covered the doings of politicians with a far greater thoroughness than in contemporary society because of the assumption that public affairs were a central preoccupation of most informed citizens. Voters demonstrated that commitment by a higher participation in elections. In 1896, for example, some 75 percent of the eligible voters in northern states had gone to the polls when William Jennings Bryan faced off against McKinley.

Presidents operated in a world of frequent elections, important party conventions, and a system of government patronage that defined their options and watched their activities. The chief executive was expected to conform to the mores of his party and to give heed to the counsel of Republican or Democratic elders. As a result, the president was not a lone wolf or free agent but had to conduct himself within the limits of existing partisan procedures.

This system seemed as strong as ever in 1897, but in fact it had already begun to erode by the time McKinley took office. As the problems of an industrial society mounted, voices were heard contending that partisanship was not the answer to the nation’s difficulties. Bosses, caucuses, and patronage seemed inefficient ways in which to manage the nation’s affairs. The discontent with politics would soon emerge during the Progressive Era, as steps occurred to limit the influence of parties through the direct primary, the referendum, and the regulatory agency. The gradual decline in the power and scope of the parties would be one of the shaping influences on how presidents functioned as the twentieth century proceeded.

Another key shift in the environment of the presidency was taking place almost imperceptibly as the nineteenth century ended. In 1896 the McKinley presidential campaign had shown a crude motion picture of the candidate in a few major cities. The phonograph was just coming into use, and inventors would soon perfect the radio as a means of transmitting voices across long distances. Newspapers were becoming more pictorial as the reproduction of photographs changed the way that readers experienced the news. It was much too early to speak of a mass media in the United States, but the various elements were coming into being. As technology accelerated, the capacity to shape attitudes, divert Americans, and affect the behavior of politicians would become a dominant fact of how presidents conducted themselves in office.

Under McKinley and later in the administration of Theodore Roosevelt, management of the press from the White House would evolve as a key tool of modern presidents. But the efforts of chief executives to stay abreast of the transformations wrought by media technology would always lag behind the pace of change in the way events were presented to the American people. Presidents would find themselves enmeshed in a culture that admired celebrity and insisted on continuous entertainment. Feeding the voracious appetite of a media-conscious culture would require that presidents take on many of the trappings of stardom themselves. In the process, the customs of show business and the lure of personality would infect the workings of the presidency in ways that had a corrupting influence on the manner of leadership in the White House.

Discussing the growth of the modern presidency has usually conveyed a benign, positive sense of an institution evolving to meet the challenges of more difficult times. Less attention has been given to the trivializing impact of balancing stardom and substance. Much of the expansion of the presidency has been policy driven, but much of it as well has been to feed the curiosity of the public about the personal character of the occupants of the White House. As the interaction between the presidency and the mass media has evolved, the effect has been to reduce the time available to the chief executive for the serious business of governing the nation. The amount of triviality has increased, but the more important impact has been to introduce continuous campaigning as a major activity of presidents. While that endeavor seems to be related to the seriousness of the office, in fact it has become a kind of mental busywork that seems more important than it really is.

Such problems seemed improbable at the end of the nineteenth century. Although the presidency was in a weakened state in March 1897, the previous generation had seen the beginnings of a revival of the office from the low point of Andrew Johnson’s disastrous administration and the two ineffective terms of Ulysses S. Grant. Presidents Rutherford B. Hayes, James A. Garfield, and Benjamin Harrison had made initial steps toward revitalizing the institution. Hayes from 1877 to 1881 had asserted presidential prerogatives over appointments and the civil service. Having limited himself to a single term, however, his efforts lost momentum as his presidency ended. Garfield continued the struggle with lawmakers in his own party and had made some progress toward establishing his rights to select federal officers before he was assassinated in July 1881 and died two and a half months later. Garfield’s death represented a missed opportunity for the revival of the presidency during the Gilded Age.7

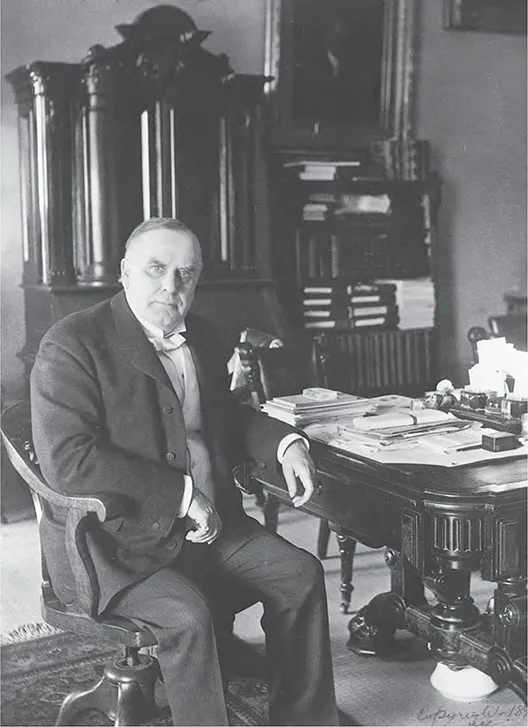

The framer of the modern presidency, William McKinley, shown here at his desk in the White House, was an innovative executive behind his conventional demeanor and conservative economic policies. (Courtesy of the Library of Congress.)

After Cleveland’s first term, from 1885 to 1889, another Republican, Benjamin Harrison, defeated the incumbent in 1888 and took office in March 1889. The new president wooed members of Congress with consultation and White House dinners. An effective speaker before large crowds, Harrison traveled across the country to push his programs and to publicize his office. He also established procedures to make the White House function on a more orderly basis. In his personal dealings with politicians, Harrison was frosty and aloof. His activism, like that of his party, did not go down well with the voters, and the Republicans suffered dramatic losses of congressional seats in the elections of 1890. Harrison served out his term but lost his reelection bid to Cleveland in 1892. Cleveland in turn finished out his rocky second term in March 1897 and gave way to the Republican victor in the 1896 election, William McKinley.8

McKinley had served in the House from 1876 to 1891, representing the district that included Canton, Ohio, and Stark County. He rose to be the chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee and made himself an expert on the intricacies of the tariff issue. He wrote the protectionist McKinley Tariff of 1890 that set the stage for Republican losses in the congressional elections. Defeated in the Democratic landslide that same year, he ran for governor of Ohio successfully in 1891 and was reelected in 1893. Soon he was being mentioned as a contender for the presidency in 1896. Popular with his fellow Republicans, he was an easy winner in the contest for the party’s presidential nomination in 1896 and then beat the Democrat William Jennings Bryan in the November election, which turned on the gold standard versus the inflationary doctrine of “free silver.”9

Despite a growing body of historical writing that has demonstrated McKinley’s strength as president, the stereotype that he was weak and irresolute has persisted. As a result, his important role in launching the modern presidency has remained obscure. Because he wrote so little about his motives, his perceptions about the need to reinvigorate the presidency and his intention to do so have not been understood. His misfortune in having the energetic and charismatic Theodore Roosevelt succeed him in 1901 also overshadowed McKinley’s contributions. Generations of historians and political scientists have simply repeated clichés about McKinley without a close examination of his performance in office.

Having watched his predecessors from Hayes to Cleveland in action, the fifty-four-year-old McKinley came back to Washington intent on reestablishing the president as a national leader. Like other chief executives, he learned on the job, too. The need to wage a two-ocean war instructed him on the wisdom of a more organized White House in 1898 and 1899. Nonetheless, these refinements grew from a basic inclination to be an activist president that he had nurtured during his years in Congress and as the governor of Ohio. His contemporaries understood how McKinley had reinvigorated the presidency, even if subsequent writers did not.

One key area where McKinley built on the precedents of the past was in his use of presidential travels to create popular support for his policy initiatives. Hayes had been called “Rutherford the Rover” for his propensity to leave the White House on extended speaking trips. Harrison also went out among the people on several long speaking tours, where his effective speaking style pleased large audiences. McKinley liked the process of crisscrossing the nation and welcomed the chance it gave him to personalize the presidency. He made several speaking swings during his early months in office to offer a contrast to Cleveland’s reclusive style.10

But McKinley’s real innovation in presidential travel came in autumn 1898 when he used the process to implement his program of territorial acquisition, following the war with Spain. Invited to attend a celebration of the fighting’s end in Nebraska, he capitalized on the cross-country journey to make his case to the people through the nation’s heartland. Not since Andrew Johnson’s disastrous “swing around the circle” at the height of the Reconstruction battle with Congress in 1866 had a president traveled during a congressional election campaign. The political reverses that Johnson suffered suggested that it would not be wise for a president to repeat the experiment.11

In 1898, however, McKinley did n...