1 Jerusalem’s Terrain

The Department Store and Its Discontents in Imperial Germany

The German department store had survived the childhood maladies of its early years. It was no longer thought of as on par with rummage bazaars and rip-off joints in the public mind; it had achieved prestige and the trust of its customers. For big retail at this time the possibilities were nearly endless… . Department store after department store has arisen in the past few years, but much more damaging than this competition has been the vilification and agitation by the owners of specialty shops… . All in all it has been an intense time, a period of frenzied progress and simultaneously of struggle, of self-defense and hard-fought success.

—Margarete Böhme (1910)

To talk about the department store question and not to emphasize that Jews are the principal carriers of the department store idea would be just as foolish as if someone were lecturing about cholera and did not wish to mention the comma bacillus.

—Emil Suchsland (1904)

“Department store fever is raging in all cities,” observed Leo Colze in a 1908 book on the Berlin department stores.1 “If someone thinks he has found a corner anywhere that seems suitable for a new department store building,” Colze continued, “he immediately tries to drum up interest in the project among investors.” Colze was writing at the peak of a veritable boom in German department store construction, the roughly fifteen-year period from the end of the nineteenth century until the beginning of World War I. In these years new retail constructions were rising at a frantic pace, rapidly creating new fortunes as well as the occasional bust. Like many other commentators in this period, Colze marveled at the rapid spread of new department stores and the enormous size and scale of new store buildings, developments that he greeted with a great deal of excitement and some measure of concern.

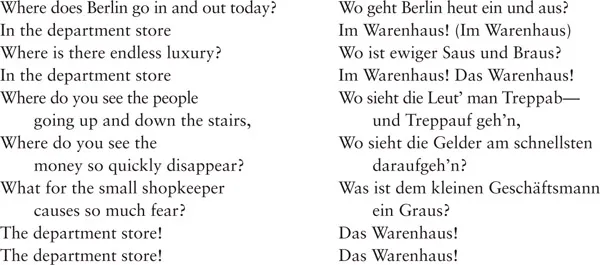

Even a more dispassionate observer like Käthe Lux, the author of a scholarly study of the department store phenomenon in 1910, could not but note how sensational department stores had become: “These vast enterprises,” she wrote, “arouse public interest in the big cities on a daily basis. This is especially the case for women who follow their announcements in the morning papers with the most excited attention.”2 This sensationalism was captured in a 1912 musical revue called Chauffeur ins Metropol! (Chauffeur into the metropolis), one of dozens of theatrical, literary, and cinematic representations of the department store from this period. The revue, which was performed at Berlin’s Metropol Theater, began its second act with the following refrain:

A tongue-in-cheek, satirical show to be sure, Chauffeur ins Metropol! nonetheless reflected the excitement modern Germans experienced around department stores, and with one well-placed line about small shopkeepers, it simultaneously signaled awareness of the other side of the picture, the vocal opposition by proprietors of smaller specialty shops, many of whom saw the department store as a grave threat to their livelihoods and to traditional German economic and social values.

Not simply a department store booster, Colze saw both sides of the issue. He credited department stores with helping to turn Berlin into a metropolis, a widespread source of satisfaction in Germany, as the recently unified state flexed its muscles in world affairs, embarked on a course of imperial expansion, and wracked up accolades in science, medicine, and increasingly the applied arts.3 He also praised the new stores for helping to modernize the German economy and to display and broadly distribute tasteful objects, necessary for the aesthetic education of the German people. Colze pronounced: “If today commercial palace after commercial palace is lining up along the major traffic arteries of the imperial capital; if illuminated display windows showing the most superb products of the collective industry of the civilized peoples are luring people in, not only for acts of purchase, but also for purely aesthetic reasons; if today even the little man is in a position to obtain luxury articles which are otherwise scarcely of any practical utility, then this is solely and singularly the achievement of the modern department store organism.”4

Colze was clearly impressed, even awed by the department stores for their architectural beauty, their feats of engineering and design, their modern commercial methods, and perhaps most of all their tremendous power and scale. Yet his text registers a certain ambivalence and subtly attends to the more ambiguous consequences of the “department store organism.” He expresses genuine consternation about the destruction of apartment buildings that was required for building the Kaufhaus des Westens (Department Store of the West, or KaDeWe) in Berlin’s still mostly residential and verdant west. He rues the increasing influence of big banks and foreign capital over the new department store businesses. (Several of the major firms in fact became publicly financed ventures early in the twentieth century, and new construction typically required enormous bank loans, such as the 2 million mark capital infusion from Deutsche Bank behind the KaDeWe.) Colze also muses about the fate of smaller merchants and specialty retailers suddenly forced to compete with these mighty department store firms. Finally, he predicts that the stores’ tremendous profits will soon wane; now that the department store phenomenon has passed through its childhood and entered maturity, he concludes, the era of rapidly acquired fortunes and new retail empires has nearly run its course.

Colze’s perspicacity, his ability to see both the department store’s contributions and its drawbacks, was rather unusual in the highly polarized department store debate that took place amid Wilhelmine Germany’s divisive political culture. German society in this period was riven by the demographic and social consequences of rapid industrialization and urbanization. To many, particularly spokesmen for the shop-owning middle classes, the department store was the very symbol of the threatening future, a seemingly untamable economic juggernaut, a conduit for American ways, and a potential leveler of the distinctions that had made social standing and gender roles legible, segmented, and stable in the old order. New store openings became flashpoints in the confrontation between a political system that was still in many ways premodern and the forces of economic modernity.5

Not merely grist for the mill of German cultural pessimists, the department store issue quickly took on political dimensions. To many critics, the new stores represented a conspicuous embodiment of the international—and specifically the Jewish—presence in Germany. At the very moment in which a handful of Jewish businessmen were creating vast, attention-getting edifices in major German cities and helping transform daily life and culture, there was a revival of anti-Jewish rhetoric throughout German-speaking Europe, carried by new political groupings and organs that decried the Jews in the shrill tones of a new era of mass political mobilization. The department store became a convenient target just as a new generation of demagogues was seeing the political utility in harnessing economic resentment and whipping up anti-Semitic rage in Germany and Austria-Hungary.

The department store, then, almost as soon as it appeared on German soil, became a lightning rod for social and political conflict, and its dynamic growth incited several waves of controversy in Germany, and elsewhere, in these years. Starting already in the late 1880s, street protests greeted new department store openings in several German cities. The issue was also debated fiercely in the public sphere, taken up in state parliaments across the country, and even addressed in the Reichstag. “Hardly a state parliamentary session goes by,” observed Lux, “without some new petition being brought forward [against] the department stores, these social-politically ‘undesired enterprises.’ ”6

In June 1899, for example, the Reichstag held a debate about department stores and how to regulate them, one of dozens of clashes between economic liberals and Social Democrats on the one side and defenders of the interests of the Mittelstand—the shopkeeping and artisanal middle classes—on the other. During this particular session, Hermann Roeren, a Center Party delegate—later known for exposing scandals in the German colonial administration of Togo—denounced the rapid spread of these “colossal businesses,” which, he lamented, were expanding and spreading at a terrifying rate, or “sprouting up like fungi,” as he put it.7 This great expansion, Roeren added, could be attributed not to the skill or cleverness of their proprietors but to the influence of the big banks and big capital. As a result, he claimed, “these businesses are engulfing the whole country; they are beginning to reach their tentacles even into the countryside and into the little towns.”8

What Colze and Roeren had in common, despite the significant differences in their temperament and tone, was a sense of astonishment at the tremendous growth and the seemingly boundless expansion of the department store phenomenon. They shared a belief in the department store’s revolutionary potential, its tremendous power over individual Germans and over the national economy, even if they assessed that power differently. Colze, for example, continually refers to department store businesses as dynasties and their directors as “kings,” who exercised sovereignty over large groups of subordinate, fawning subjects, their eager customers. He writes, for example, that “in thick packs and ceaselessly they stream in: the ruler calls, they follow gladly.”9 Such evocations of the department store’s power course through the abundant contemporary literature on the phenomenon by the stores’ boosters and critics alike.

A great many of those accounts, to be sure, trafficked in anti-Semitic imagery, and their authors portrayed the department stores as a manifestation of Jewish capitalism, as the latest example of pervasive and nefarious, but often hidden, Jewish economic power. “Once a Jew always a Jew [Jud’ bleibt Jud’],” mused Theodor Ribbeck, an artisanal shopkeeper in Margarete Böhme’s 1911 novel W.A.G.M.U.S., as he pondered the ambitious expansion plans of the (baptized) department store owner Josua Müllenmeister (né Manasse). “A Christian wouldn’t be able to pull all of this off. Whether Müllenmeister or Manasse, Israel holds all the cards. Step by step Jerusalem increases its worldly terrain.”10

Other than a minority of non-Jewish businessmen, who did in fact “pull it off,” Germany’s leading retail entrepreneurs at this time, Nathan Israel, Adolf Jandorf, Oscar and Leonhard Tietz, and Abraham Wertheim, were of Jewish origin. Jews founded the great majority of department stores throughout Germany, and Jewish businesses accounted for around 80 percent of total department store sales volume in the Weimar period, according to one frequently cited but not wholly reliable estimate.11 The number was most likely higher before World War I, before many small, Jewish-owned firms were absorbed by the Karstadt company. Most of Colze’s readers would have certainly been aware of the department store’s entanglement with Jews and Jewishness: the affluent Jewish department store owner had become a stock character in novels like W.A.G.M.U.S., and was emerging as a political scapegoat and even a cultural cliché. Indeed, the department store itself was widely seen as a Jewish phenomenon, by opponents, supporters, indifferent passersby, and eager customers.

Colze’s text, however, differs from the standard anti-Semitic critiques and caricatures. A reference to Rabbi Akiva in the middle of the book is the first hint of the author’s Jewish background. In his subsequent discussion of his maternal grandfather, whom he calls the Marshall Field of the 1860s, the “department store king” of his shtetl, the author subtly but unmistakably reveals his Jewish identity. Colze, it turns out, was actually one of several pen names used by the writer, publisher, and corporate attorney Leo Cohn.

Notwithstanding the idiosyncrasies of Colze’s position, the department store debate was generally conducted in shrill and hyperbolic tones, with little room for nuance. Anti–department store writings were suffused with dire warnings of Germany’s demise and filled with morbid, even supernatural images meant to lay bare the parasitical effects on the German middle classes of Jews, commercial capitalism, or both. Similar debates occurred elsewhere, chiefly in France, and also in the United States and Britain, but the German debate was marked with a particular venom against department stores and what they were believed to represent. It also started later and lasted much longer, marked by several distinct phases: first from the 1890s through the early 1900s, briefly, again, after World War I when the Nazis joined the fray, and then again in the later 1920s. It reached a crescendo with the economic crash of 1929, the subsequent unemployment crisis, and the Nazi rise to power.

A Revolution in Retail? Department Store versus. Specialty Shop

The nine years between Roeren’s Reichstag speech and Colze’s volume bookend the first of two peaks of German department store expansion. A second department store boom occurred in the 1920s, during the brief but dynamic years of economic stability in the Weimar Republic. A decade before Roeren’s 1899 address, there were scarcely any department store...